ONLY A SELECT FEW get the chance to escape Earth’s bubble, fewer will set foot on another orb, and fewer still will sit at the helm of a spacecraft. Of the 18 travelers NASA has tapped for its Artemis missions, which will bring people to the moon for the first time in more than a half-century, it is the pilot who must ferry the crew safely, pulling off historic landing maneuvers in an untried spaceship.

A likely candidate to sit in that chair is Victor J. Glover, who’s spent much of his 20-year career soaring across the heavens as a Navy test pilot and is among a new generation of astronauts aiming to create a permanent base camp on the moon’s surface. Artemis 3, which NASA intends to launch in 2025, will land two travelers for a six-day reconnaissance survey. The goal is to search our satellite’s southern craters for pure frozen water and scope out ideal spots for a way station.

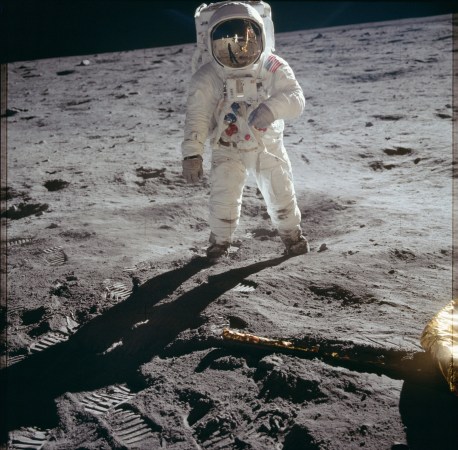

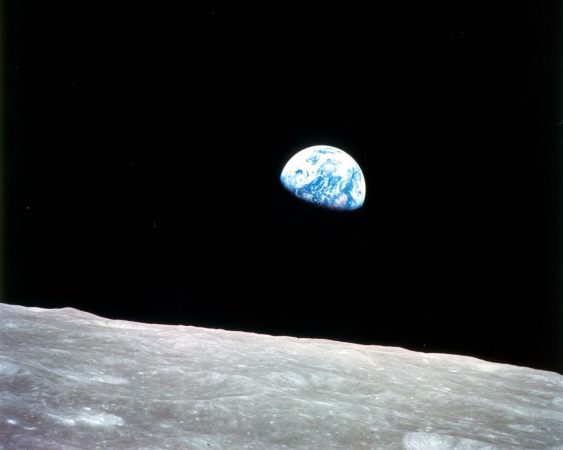

Despite NASA’s return to form, Glover himself knows that this decade’s moonshot will look vastly different from the Apollo missions, which ran from 1968 to 1972. Though the midcentury launches established the technology needed to achieve US preeminence in space, “We’ve learned a lot in those 50 years,” Glover says. “So there are lots of ways that we have advanced hardware, software, and even people, policy, and procedures.” To level up, the Artemis cohort will undergo much more intense and extensive drilling than any Americans launched beyond Earth in the past.

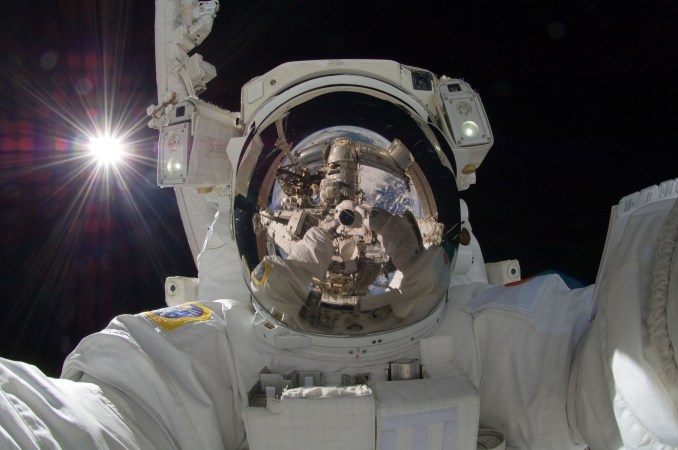

When training to survive beyond the safety of Earth’s atmosphere, potential crew members have to be ready for almost every possibility. That is to say, there are no typical days when you’re going through spaceflight drills. Sometimes Glover and the other trainees would spend six hours submerged in a pool to prime their bodies for death-defying spacewalks aboard the ISS. Now he curls his brain around long-winded Russian lessons for multinational missions, and he will soon be performing simulated moonwalks in NASA’s Neutral Buoyancy Lab.

But the best preparation he’s had for venturing into the solar system is piloting here on Earth. He’s logged 3,000 flight hours on more than 40 kinds of jets and planes, including the F/A-18 and the Boeing EA-18G Growler. That versatility, which includes handling war craft in perilous situations like the Iraq War, should help him steer a brand-new Orion capsule and SpaceX Starship landing system to an untouched part of the moon.

Setting the craft down also presents challenges. Once Artemis 3 enters lunar orbit, the crew will have to vertically orient the Starship rocket, which is streamlined to maneuver in thinner air and on a powdery surface. It’s one of the reasons the mission’s astronauts have been learning to fly helicopters, which use similar mechanics to descend and ascend.

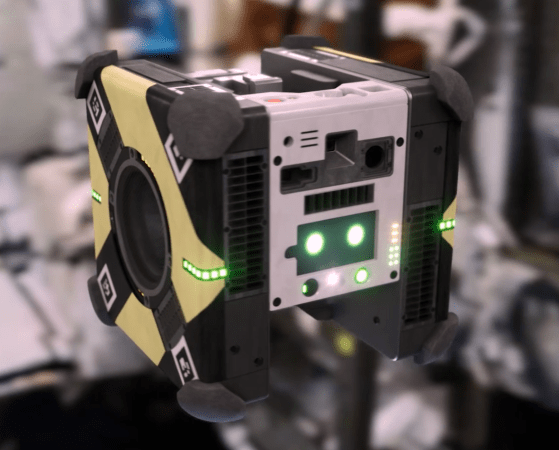

The Artemis 3 journey will be double the length of Apollo 11’s, so its technologies have to facilitate endurance. The Orion vehicle is powered by solar arrays, will be able to transport four people (one more than its Apollo counterpart), and has a heat shield reinforced with carbon fiber and titanium to protect against the hostile temperatures and radiation of reentry. Lastly, in contrast to the analog setups of the last lunar program, Orion’s guidance, navigation, and control system includes advanced automated software that will free up the astronauts to complete other tasks, such as doing research and getting exercise.

While it’s still up in the air whether Glover will be the pilot for the next moon landing, he’s already adapting to the challenge. In fact, much of his confidence comes from being guided by former NASA flight controllers and directors, who are happy to see their wisdom being used to reach for new heights. “You often hear people talk about going to space and they say it is a marathon, not a sprint,” Glover says. “I actually will say no, this is a relay race, and they have handed us the baton.”

This story originally appeared in the High Issue of Popular Science. Read more PopSci+ stories.