Donald Trump isn’t the first president to suggest we send people back to the moon, but his recent declaration sparked a lot of questions here at PopSci. Being science journalists, we went ahead and answered those queries, then compiled them here in case you’re curious, too.

Won’t going back to the moon inspire people to become scientists?

If you were a kid in 1969 who watched man first set foot on the moon through a crackling television, you may have been awe-inspired enough to want to become a scientist or an astronaut. Going back won’t have quite the same effect. Yes, we could do more advanced experiments up there and come back with better footage, but it’s not a massive feat the way it was when our computers were basically just calculators.

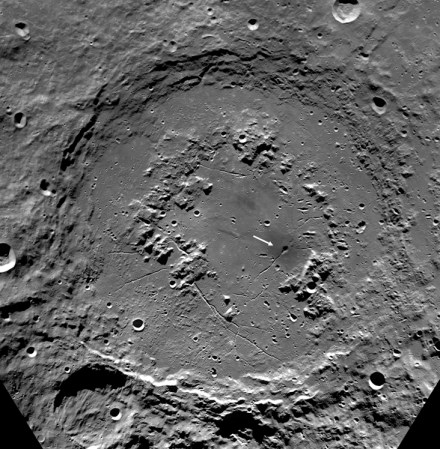

How much of the moon have we actually seen, and does anyone think we should see more of it?

The Apollo 11 crew (the first to touch down on the lunar surface) explored an area smaller than a soccer field. There are certainly plenty of experts who would like to learn more, especially about the dark side, which faces away from Earth and is harder to visit. We don’t know a lot about lunar geology, either, and more direct sampling could help us understand how the big cheese formed. It’s not that no one thinks we can learn more, it’s just a question of how valuable that information is compared to what else we could fund with the same money. Then again, that argument could be made against pretty much any space expedition.

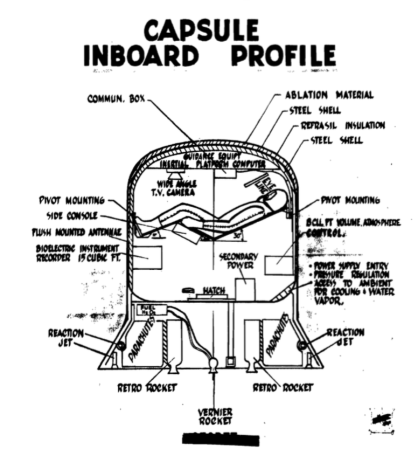

How different is the space ship they’re going to use to get there? Will it be a shorter, safer trip?

Neither Trump nor Vice President Pence have given any specifics on how exactly we would return humans to the moon. That being said, NASA would probably do it with their Space Launch System, which is going to replace the space shuttle (retired in 2011) for ferrying people to the International Space Station and eventually (maybe) help get humans to Mars. It would undoubtedly be safer than the original space shuttle, if only because we have better technology today, but it wouldn’t be without risk. Sticking humans on top of a rocket and shooting them into space is dangerous no matter what.

The trip probably wouldn’t be much shorter, though. The safest way to make sure astronauts return to Earth is to use a free return trajectory, where you launch the rocket at precisely the right time and velocity so that it doesn’t require any more adjustment—once it leaves Earth’s orbit, it falls into the moon’s, loops around, then comes back. This took Apollo missions about 2.5 to 3 days. If we wanted to go back, we wouldn’t be shaving much time off of that estimate simply because the capsule has to move at particular speeds in order to enter the moon’s orbit. A craft going to fast would zip right past.

If humans lived on the moon, would we have to live in tunnels under the surface?

We could build moon habitats on the surface. But we’d have to watch out for bits of meteors and particles from solar flares that slam into the satellite, because there’d be no atmosphere to protect us. The ideal real estate is at the poles, since the rest of the moon experiences 14-day-long nights (and days), and temperatures range from 253 to -387°F. You don’t get these extremes at the poles, so we could take shelter in the perpetual twilight. Which sounds suuuuuuuper fun.

Why does Donald Trump want to go to the moon?

Look, it makes sense to have nostalgia for the time when we just got all our crap together and got ourselves to the gosh-darned moon. It’s true that the Apollo missions were good for patriotism in the U.S.—heck, that’s why President Kennedy wanted to go in the first place. We’re just not convinced that going back will inspire the same blind enthusiasm that the original mission did.

What do we have to gain by sending humans, not robots, to the moon?

It’s certainly cheaper and safer to send a ‘bot. Crewed missions require capsules equipped with life-support systems, and you have to gently land people on the surface. Robots, on the other hand, often land in a sort of semi-crash. All that extra design, weight, and gear costs money. Plus, you risk those human lives. If a robot gets destroyed in the process, we’ve lost the time and money we invested, but no one got all the way to the moon only to die there. Which the people who sent men to the moon were always prepared for, by the way.

Why send humans instead? Some people actually argue that robots should handle all of our future space expeditions. But it’s true that humans are much better at thinking on their feet (at least for now). Other than that, it’s mostly a spirit-of-exploration kinda thing.

What kind of science do we miss out on if we pay for a trip to the moon?

NASA’s most recent estimate put the cost of another moon trip at roughly $10 billion. It’s not a precise trade-off with other federally funded science, because we can’t know what pennies would be pinched and where to scrape that funding together. But to put the number in perspective, we could fund the entire National Parks Service about three times over with that money. They have a backlog of maintenance right now that’s hovering at $12 billion, so we could almost wipe that out with our hypothetical moon money.

Or we could put that cash toward the National Institutes of Health, which operates on a $35.6 billion budget. An extra $10 billion would mean a lot of much-needed grants for scientists investigating ways to cure Alzheimer’s disease and treat all types of cancer. Funding is scarce, and researchers often spend huge chunks of their time trying to find money rather than actually researching.

We could also almost triple the Office of Science’s budget. The Office of Science is part of the Department of Energy, and is the biggest sponsor of physical science research in the U.S. They fund all of the national laboratories and have produced 76 Nobel Prize winners. Think of how many we could produce with another $10 billion!

If we want to stick to space spending, that money could chip off about 10 percent of the price of going to Mars, or fund something like 14 missions like New Horizons, which studied Pluto and is soon to investigate a strange new object. We could also have three Cassinis. Three! Cassinis!

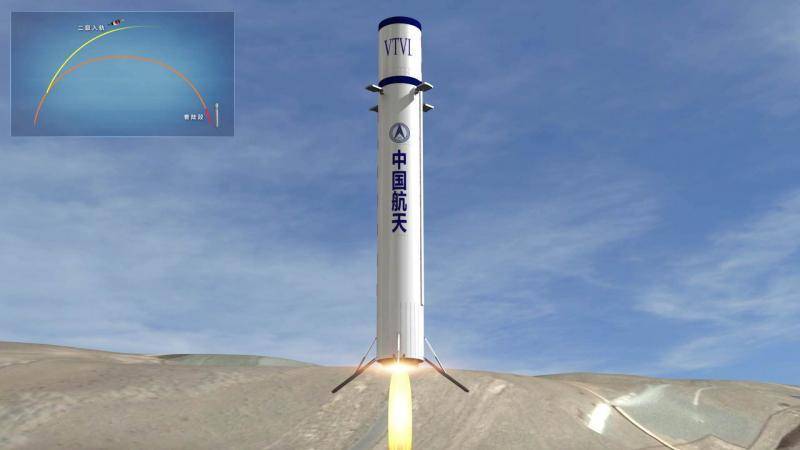

Who’s going to the moon?

Many agencies (including NASA) have robotic missions in the works. Several contestants in Google’s Lunar XPRIZE are set to land in the next few years, with various plans to hop and rove around. India’s second lunar mission, Chandrayaan-2, is slated for launch in 2018 and will include an orbiter, lander, and rover. China’s Chang’e 4 should land on the far side of the moon later that year. NASA will send the Orion spacecraft into lunar orbit in 2019 (without anyone onboard).

But when it comes to human missions, all existing plans are still in the wishy-washy stage of development. Elon Musk recently claimed that SpaceX would send two private citizens on a lunar fly-by by late 2018. A crewed test of the Orion spacecraft is supposed to take astronauts into lunar orbit by 2020, but that date is really rather up in the air until we nail the uncrewed version of the test.

Russia plans to launch a crewed orbiter in 2028 and land humans on the moon in 2030. Japan also has a 2030 landing supposedly in the works, while China plans a landing for 2036. The Russian agency Roscosmos has talked about plans to have some kind of lunar base by the 2030s. But all of these missions are in the very earliest stages of planning, and could very well be scrapped.

Is there any reason we should or aren’t trying to go to the dark side?

Because our planet’s tidal forces have slowed the moon’s rotation, Earth always sees just one hemisphere of our satellite while the other half always looks away. But it’s not actually dark. Each half sees two weeks of sunlight or darkness at a time. So if the far side isn’t some eternally black hellscape, why didn’t we ever go there? The answer is pretty simple: the moon blocks radio communications from Earth. When astronauts took a slingshot around the far side on their way back home, they were totally incommunicado until they emerged on the other side.

But astronaut Harrison Schmitt, a geologist who flew on Apollo 17, thought it was a shame to leave the far side unexplored. He proposed a plan to put a communications satellite out beyond the moon, positioned in orbit so as to keep NASA in touch with astronauts on the far side. Unsurprisingly, this extra planning, hardware, and launch was deemed too expensive. But in theory it could be done!

So far no one has picked up data from the surface of the far side (though astronauts and orbiters have seen it many times). NASA’s Ranger 4 probe impacted the surface in 1962, but it didn’t return any scientific data. If China’s Chang’e 4 lands on the far side as planned in late 2018, it will be the first probe to successfully do so. China will first launch a communication relay station to facilitate contact with the robot.

Why go to the dark side? It’s not just like the part of the moon we’ve landed on stretches out in all directions, unchanged. Most of the hemisphere we’ve stomped on is made up of “maria” (named because scientists once thought they were seas of lunar water), which are plains formed by ancient volcanic activity. The far side is mostly made up of craters, and scientists aren’t totally sure why it’s gotten more of a battering. But is it worth the cost of a crewed mission when we could send better robots and orbiters? Doubtful. Still, perhaps a trip to the never-before-touched far side could inspire the kind of public fervor NASA accomplished with its first missions.

Would the moon make a good base to launch missions to Mars?

There’s really no straight answer to this, because folks disagree. Both politicians and engineers have made vague proclamations about the moon being a stepping stone to Mars, and they don’t always mean that literally.

Okay, so what are the benefits of literally launching from the moon? Sure, the gravity is lower, so it would take less fuel. But to take advantage of that, we’d have to have such a sophisticated moon base that we could create and build every bit of the rocket and launch pad on the lunar surface. Otherwise, we’d just be shipping all the pieces up to the moon and then using another mess of fuel to launch it a second time. And if low gravity on the moon is good, wouldn’t zero gravity in space be better? Build an orbiting space launch base! Or don’t—that would be expensive.

There are other, less literal, more realistic ways the moon could serve as a stepping stone. Some research suggests we should launch Mars-bound rockets with just enough fuel to get to the moon—as long as we can figure out how to turn lunar water-ice into fuel for the rest of the trip. The viability of this plan is definitely TBD. Then there’s the idea that sending folks to the moon will help us get our sea legs by improving our rocketships, space suits, extraterrestrial homesteading skills, and general astronaut preparedness. That’s a good point, but one could also argue that the funds and time we divert to moon exploration could simply be poured into an aggressive gun for Mars itself.

Haven’t we said we were going back to the moon before?

Yup. The Washington Post has a helpful rundown of all the presidential space promises that have been for naught. But if we’re just talking about returns to the moon, President George H.W. Bush and President George W. Bush made such declarations. President Obama scrapped the latter Bush’s program in favor of renewed vigor toward Martian exploration.