Pence says U.S. rocket companies will put astronauts in space this year. U.S. rocket companies aren’t so sure.

Rocket engineering turns out to be even harder than rocket science.

With all the glory of the Apollo lunar landings, it can be easy to forget that the Soviet Union beat the U.S. to most other milestones during the space race. Sputnik 1 was the first satellite. Laika, the first animal (dog) in orbit. Yuri Gagarin, the first person. For the last eight years, the Russia’s Roscosmos has regained another bragging right: it’s the only organization on the planet capable of getting humans to the International Space Station.

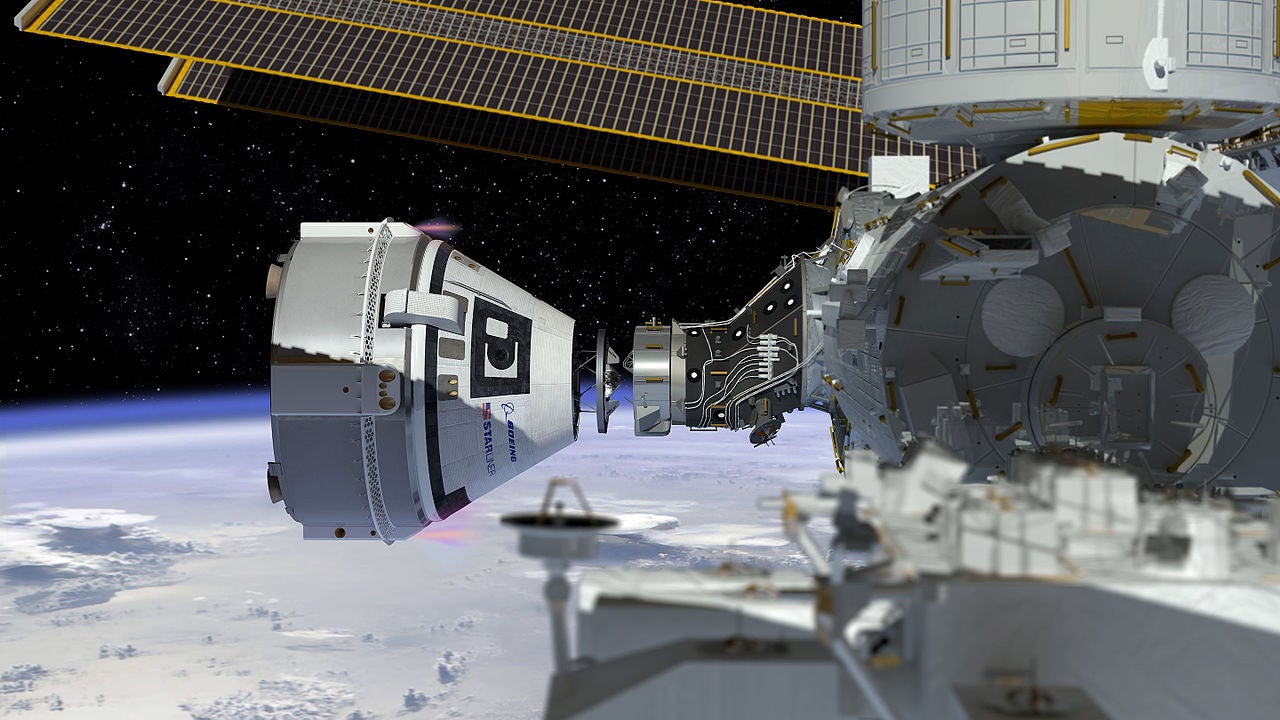

Ever since the last space shuttle landed in 2011, the crewed U.S. space program has been stranded without a ride to the International Space Station (ISS). NASA has rockets, but without a capsule capable of carrying astronauts the agency has resorted to purchasing seats on the Roscosmos’s Soyuz capsule—recently for 82 million dollars each. Eager to regain independent, affordable access to space, NASA has paid two private U.S. companies to develop crewed capsules for them. Boeing is building the Crew Space Transportation (CST)-100 Starliner for 4.6 billion dollars, and SpaceX received 2.6 billion dollars to develop the Crew Dragon.

After years of delays, launch day appears to be getting closer. On Tuesday, at the sixth public meeting of the White House National Space Council, NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine said that Boeing and SpaceX are “on the brink of being ready.” Vice President Mike Pence, who chaired the meeting, spoke even more forcefully. “Before the year is out,” he said, America will send astronauts to space on American rockets from American soil.

Before booking Christmas vacation at Cape Canaveral, however, consider that Tuesday wasn’t the first time NASA and the administration have trotted out this talking point.

Here’s Bridenstine talking to USA TODAY in August 2018: “Without question, by the middle of next year, we’ll be flying American astronauts on American rockets from American soil.”

And again in April: “By the end of this year,” he repeated at a House Science Committee hearing, “we will be launching American astronauts on American rockets from American soil to the International Space Station.”

NASA originally hoped to have a shuttle replacement in place by 2015, but soon pushed back the goal to 2017. Since then, the dates on which Boeing and SpaceX were supposed to receive certification to fly astronauts have slipped no fewer than nine times for each company, according to a report from the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) published in June.

Fault lies on both sides. In the early years, NASA failed to adequately fund the projects, the agency found in 2016. Later delays, however, have been technical. Boeing had trouble dealing with powerful launch vibrations, and SpaceX changed their capsule to land at sea rather than on land. The science of tossing a vehicle into orbit may be pretty straightforward, but actually designing and building a spacecraft that keeps astronauts safe is, it turns out, anything but. Now, even representatives from the rocket companies themselves aren’t sure if they’ll make the current 2019 deadline (neither company responded to requests for comment).

Meanwhile NASA, whose Roscosmos contract expires in September 2020, is watching their progress closely. Here’s where each company stands.

Boeing The CST-100 has the farthest to go, with two tests standing between it and its first crewed launch. First, it will conduct an “orbital flight test,” launching on an Atlas rocket, docking autonomously with the ISS, and returning to Earth, all with no one aboard. If successful, Boeing will follow up the orbital flight test with a “pad abort test”—where the CST-100 checks its safety features by blasting away from its rocket on the launchpad and using parachutes for a soft touch down nearby. After those two tests, three astronauts—Nicole Mann, Mike Fincke, and Chris Ferguson—will fly in the Starliner for the first time.

Boeing aims to start the tests this fall, and the recent GAO report lists Boeing’s target crewed certification date as January 2020, falling short of Pence’s promise.

“We’re making real good progress on getting the Orbital Flight Test vehicle to the pad and ready to go,” said Peter McGrath, Boeing’s director of global sales and marketing for space exploration at a panel discussion in Indiana on Monday. “We’re heading towards an Orbital Flight Test in October.”

No Boeing flight currently appears on NASA’s launches and landings manifest, which covers events until October 3.

SpaceX Pence may be hoping that SpaceX squeaks in a crewed launch before the New Year, as the California-based company has a slight lead on Boeing. SpaceX faces a similar three-step path to getting astronauts onto the ISS, and has already cleared the first test. The Crew Demo-1 orbital test launched March 2 atop a Falcon rocket, docked with the ISS, and returned successfully to Earth. While preparing for an upcoming “in-flight abort test,” however, a leak caused an explosion on April 20, destroying the Crew Dragon capsule, and along with it any hopes of flying a crew on Crew Demo-2 in July.

Later in the summer, SpaceX representatives hinted that the company may miss the end-of-the-year deadline. “By the end of this year, I don’t think it’s impossible, but it’s getting increasingly difficult,” said Han Koenigsmann, SpaceX’s vice president of Build & Flight Reliability, on a conference call reporting the results of the company’s explosion investigation.

Recent comments, however, have been more positive. On Monday’s panel, Koenigsmann said the company is targeting October or November for its in-flight abort test. “Right after that, hopefully this year, we’ll have the Demo-2 flight,” he said, Jeff Foust of SpaceNews reports. SpaceX’s first passengers, whenever they fly, will be NASA veterans Bob Behnken and Doug Hurley.

Maybe Pence’s pronouncement springs from some unknown insider info, but Wednesday wasn’t the first time he’s floated a timeline that one might charitably describe as extremely optimistic. He also expects NASA to make some new footprints on the moon in 2024—four years earlier than the agency has planned—with no extra money to do so.

Regardless of whether Boeing and SpaceX crewmembers make it to the ISS before the ball drops, with recent timeline slips shrinking from years to months, it seems likely that NASA’s ride will be arriving soon.

Correction: A previous version of this article mistakenly implied that only Russia has the capabilities for crewed spaceflight. This has been corrected.