If a cloud of dust swoops through Mars and no astronaut (or Martian) is around to hear it, does it even make a sound?

The answer is yes, according to a study published today in the journal Nature Communications. An international team of scientists used a microphone on NASA’s Perseverance rover to pick up the first-ever audio recording of an extraterrestrial whirlwind.

“We can learn a lot more using sound than we can with some of the other tools,” said Roger Wiens, a professor of earth, atmospheric, and planetary sciences in Purdue University and co-author, in a statement. “They take readings at regular intervals. The microphone lets us sample, not quite at the speed of sound, but nearly 100,000 times a second. It helps us get a stronger sense of what Mars is like.”

[Related: Saying goodbye to NASA’s InSight lander before it’s buried in Martian dust.]

Weins is the principal investigator of Perseverance’s SuperCam, a suite of tools that make up the rover’s “head.” It includes advanced remote-sensing instruments, spectrometers, cameras, and the microphone. On this study, he worked with corresponding author and planetary scientist Naomi Murdoch, a team of researchers at the National Higher French Institute of Aeronautics and Space ,and NASA.

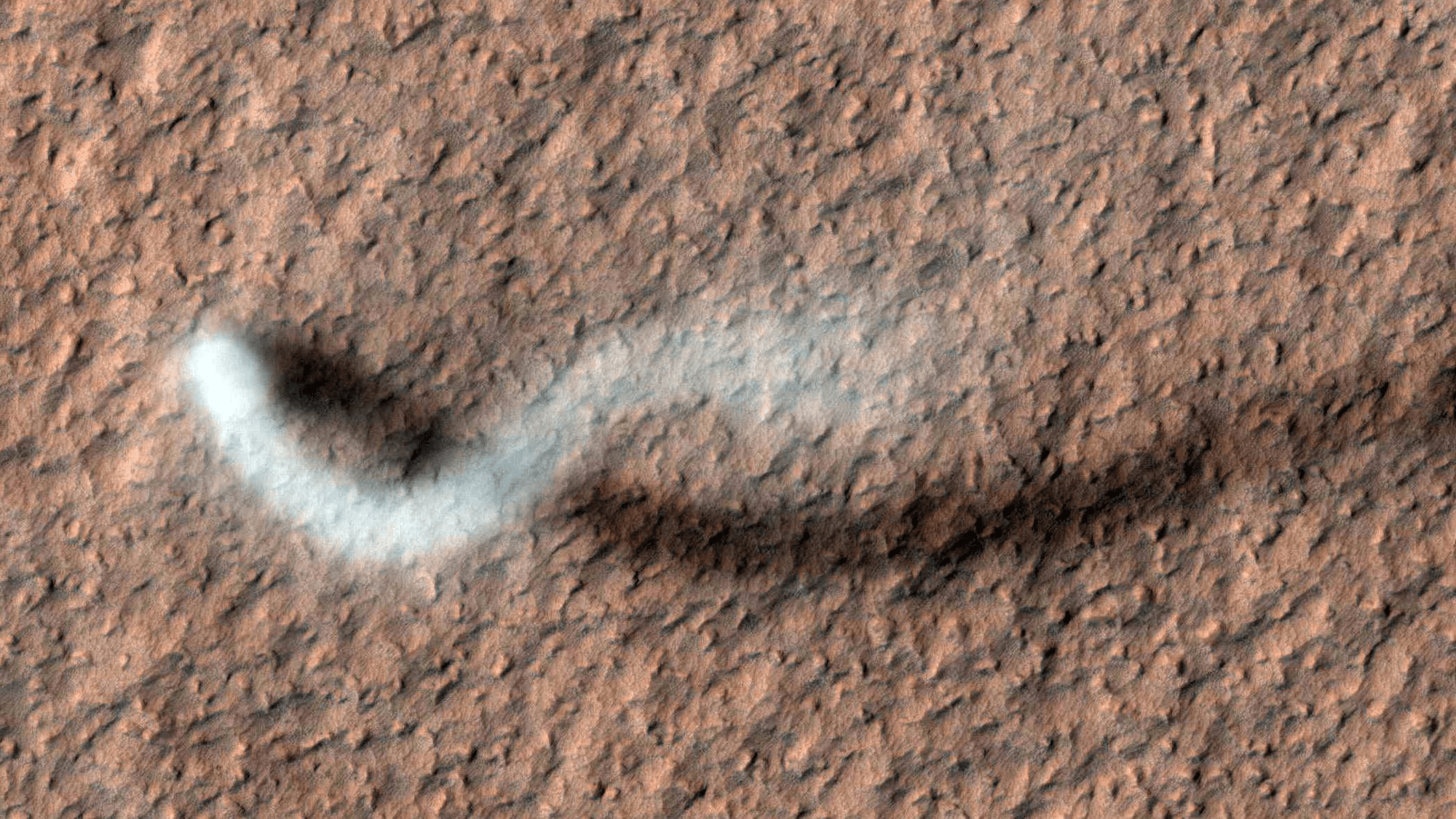

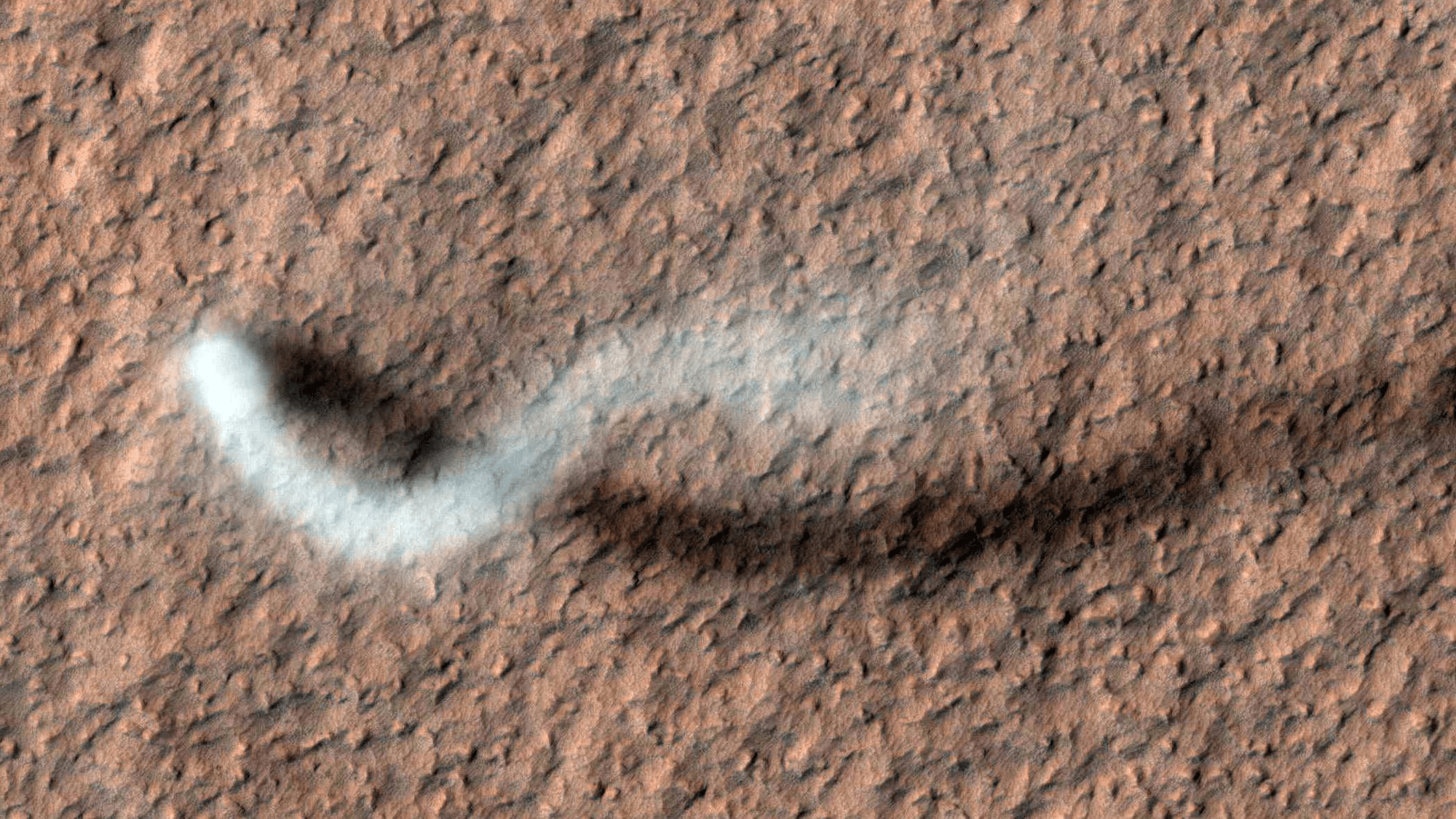

Perseverance’s microphone is not running continuously, but records roughly three minutes per day every few days. Getting the recording of the whirlwind was lucky, but not necessarily unexpected according to the team. They have observed evidence of about 100 dust devils in the Jezero Crater since February 2021, when Perseverance first landed in Jezero.

These dust devils are tiny tornadoes of dust and grit and are common on Mars. They are a sign of disturbances in the atmosphere and are an an important lifting mechanism for the Martian dust cycle. Impacts from dust grain build up is associated with degradation of the hardware on Martian rovers, so improving our understanding of how dust lifting works on the Red Planet will be helpful in future space exploration.

This recording happened because it was the first time the microphone was switched on when a dust devil passed over Perseverance. When recordings like this one are taken along side time-lapse photography and air pressure readings, it can help scientists better understand the weather and atmosphere on Mars. Analysis of the data from Perseverance’s multiple sensors and modeling suggests that the dust devil in the recording stood at over 387 feet tall.

“We could watch the pressure drop, listen to the wind, then have a little bit of silence that is the eye of the tiny storm, and then hear the wind again and watch the pressure rise,” said Wiens. “The wind is fast—about 25 miles per hour, but about what you would see in a dust devil on Earth. The difference is that the air pressure on Mars is so much lower that the winds, while just as fast, push with about 1 percent of the pressure the same speed of wind would have back on Earth. It’s not a powerful wind, but clearly enough to loft particles of grit into the air to make a dust devil.”

[Related: Happy Mars-iversary, Perseverance.]

Future astronauts exploring Mars necessarily won’t have to worry about gale-force winds taking down habitats or communications antennas and the Martian wind may even have some benefits. The team speculates that the breezes that blow dust and grit off the rover’s solar panels may help them last longer. Mars’ InSight lander is in its final days after over four years of exploration, since it is losing power in its solar panels due to dust build up.

“Those rover teams would see a slow decline in power over a number of days to weeks, then a jump. That was when wind cleared off the solar panels,” said Wiens.

Additionally, the lack of such wind and dust devils in the Elysium Planitia where InSight landed may help explain why that mission is winding down.

“Just like Earth, there is different weather in different areas on Mars,” said Wiens. “Using all of our instruments and tools, especially the microphone, helps us get a concrete sense of what it would be like to be on Mars.”