Once upon a time, in the lowest part of Gale Crater on Mars, there was a lake about the length and width of one of the Finger Lakes in upstate New York. It was fed by rivers that ran into it. If you stood on its shores, you might have seen snow or ice capping the mountains in the distance.

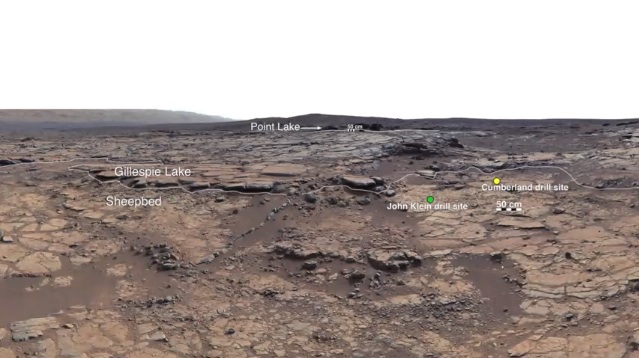

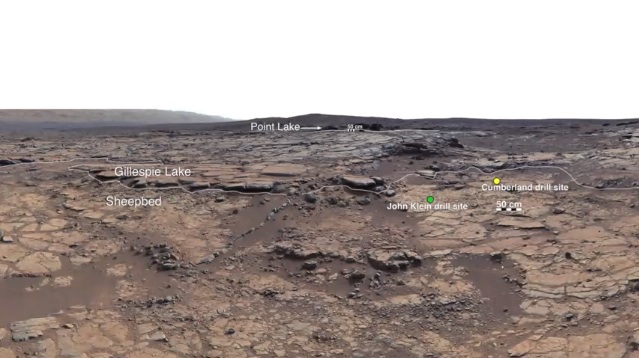

After its first 100 Mars-days, or sols, on the Red Planet, NASA’s Curiosity rover trundled down into this now-dry lakebed. The rover took images of rocks along the way and drilled two holes to take samples. It’s from these samples scientists determined this lake existed and that its waters weren’t too alien, after all, compared to water on Earth. The water was of relatively neutral pH and low salinity. “I would be pretty confident it would be fresher than seawater,” says Scott McLennan, a geoscientist with Stony Brook University in New York who worked on this and other studies based on Curiosity data.

This is water that microbes could have lived in, although Curiosity found no direct evidence of life on Mars, nor is it designed to do so, McLennan tells Popular Science.

The findings are part of a second big batch of papers, being published today in the journal Science, to come from Curiosity. In the first batch, scientists characterized some of the soils Curiosity encountered and determined there’s some water in Martian dirt that future human visitors might be able to extract. In this set of discoveries, scientists learned more about the history of water, rocks and radiation in the Gale Crater. They also determined where to look for organic compounds, molecules that are necessary for most life forms and are made by life forms. Scientists have not yet found abundant organics on Mars, but think it’s still possible to unearth (unmars?) them, if they look in the right places. The trouble is that the Martian surface is exposed to radiation that breaks down organic compounds, even if they ever did once exist on the planet.

Below are highlights from today’s findings. I’ve linked below to where Science says free versions of the papers will be posted. However, since they don’t seem to be posted yet (I get 404 messages when I try them), I’ve also included links to the papers on Science‘s website, where you may only see the abstracts.

Liveable real estate

In Yellowknife Bay, Curiosity saw layers of rock scientists think were deposited by rivers draining into a low-lying lake. Curiosity found only low amounts of salt in the rock, plus minerals that wouldn’t have lasted if that water weren’t neutral. It also found minerals that show the water once held compounds important for certain Earthly bacteria called chemoautholithotrophs, which get their energy from breaking down minerals in the rocks around them.

“We have lots of evidence from ancient rocks on Earth of microbes that would have been able to exist in exactly the same environment,” McLennan says.

Researchers think Gale Crater’s water would have come up from the ground fairly fresh, and then changed in character as minerals from the surrounding rocks dissolved into it. Sediment in the crater also indicate that water must have existed there over about 1,500 years, though those calculations aren’t exactly precise—it could have even been tens or hundreds of thousands of years. The lake probably dried up sometimes, then could have refilled from the groundwater Mars once had. Geochemists are still working out the details.

(See the original paper here or at Science.)

The search for organics

One of Curiosity’s instruments blasts samples with heat and then examines what gases the rocks release. Some of this analysis discovered evidence of carbon and nitrogen on Mars, both of which are necessary for life. Scientists weren’t able to tell whether the carbon came from minerals or organic molecules, however.

(See the original paper here or at Science.)

Scientists did not find further evidence of organic molecules because of the intense cosmic radiation that beats down on Mars through its thin atmosphere, Jennifer Eigenbrode, a NASA Goddard scientist, said during a webcast press conference. But another research team is trying to get around that. The team modeled how wind has weathered rocks in Gale Crater. Their results show where to drive Curiosity to find rock surfaces that were more recently weathered and have been exposed to radiation for less time. Those rocks may still contain intact organic molecules.

(See the original paper here or at Science.)

Radiation barrage

One team measured the radiation Curiosity experienced over about 300 days. The measurements show what any past microbes would have had to deal with, and what any future human visitors will have to shield themselves against.

Astronauts who fly to Mars, stay there for 500 days, and then fly home again would be exposed to about 1,000 millisieverts of radiation. That’s more than 10 times as much radiation as an astronaut receives during a six-month stay on the International Space Station.

(See the original paper here or at Science.)

And more

One study published today characterized the mineral content of rocks taken from the two centimeters-deep drillholes Curiosity made. This analysis told scientists more about when those rocks formed in Mars’ history (See the original paper here, or at Science).

Another paper determined one sampled rock was created during a cold, dry period, showing that Mars’ geological history was diverse, including both wet and dry times (See the original paper here, or at Science.)