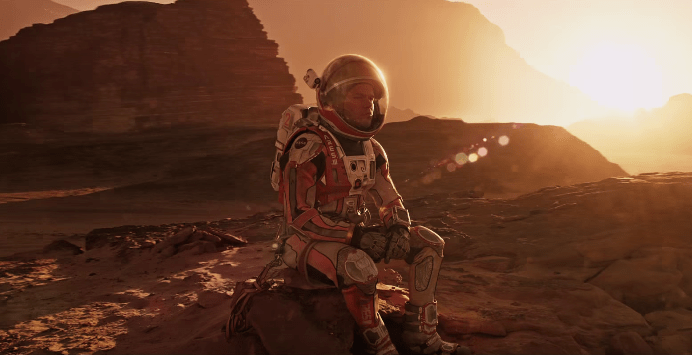

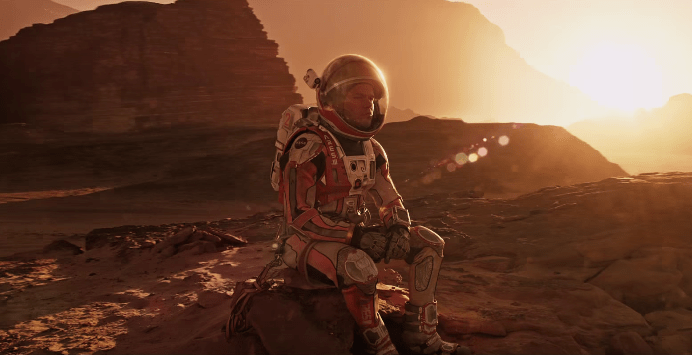

It almost feels wrong to label The Martian as science fiction. Based on the book that computer programmer Andy Weir researched for three years, the movie feels like it could happen in real life any day now. You’ll find no suspended animation, jump drives, or wormholes in this flick—just technologies that NASA is already using or could develop in the near future.

True, in real life we’re not headed for Mars anytime soon. America doesn’t even have a spacecraft to get us there, let alone a habitat to keep us alive while we’re there. But if and when we do go to Mars, it’s probably going to look a lot like you’ll see in The Martian, according to a panel of NASA scientists and engineers who spoke at Columbia University on Sunday.

“To the level of detail that you see in the film and in the book,” Dave Lavery from NASA’s Solar System Exploration program told Popular Science after the panel, “it overall is actually pretty closely in line with what we’ve been thinking.”

Warning: Mild spoilers follow, but we won’t give away any major plot points.

Quibbles

The scientists that Popular Science talked to were hard-pressed to really find fault with the movie. But there are a few persnickety things, which actually originate from the book–although The Martian is now getting lots of love from NASA, when Weir started writing the story, it was just a blog. Here are a few of the minor issues these scientists spotted that aren’t exactly true to life.

The Sandstorm

This is a big one, and it’s one that’s been harped on before. At the very beginning of the book, a sandstorm causes astronaut Mark Watney’s crew mates to leave him for dead, abandoned on Mars. Although Mars does have huge, powerful sandstorms, the destructive force of the storm is lessened in real life by the planet’s thin atmosphere and low gravity (about 1/3 of Earth’s).

“Yes, we do have 100-mile-an-hour dust storms on Mars,” says Lavery, “but they have the inertia and the dynamic pressure associated with an 11-mile-an-hour wind on Earth. So you wouldn’t get that level of damage, or big pieces flying through the air, causing all these events to happen.”

Real Martian sandstorms do have at least one potentially deadly force, though, says Lavery: lightning. “We haven’t actually photographed a bolt of lightning on Mars yet, but we’ve seen ground traces before and after lightning has occurred. It’s associated with these sandstorms. Andy [Weir] has said ‘Had I known that at the time, I would have had lightning make this whole thing work.’”

The RTG

Without including too many spoilers, at one point, Mark Watney has to dig up a radioisotope thermoelectric generator (RTG). Originally used to charge the mission’s Mars Ascent Vehicle, it was later buried to protect the crew from any potential radioactive emissions. NASA really does use RTGs—the Curiosity rover is driving around with one right now—but Lavery says NASA would never choose to bury an RTG. That’s because the plutonium inside stays hot for a very long time.

“Mars has got a fairly significant storage system for water,” Lavery says. “Most of it is basically frozen mud in the subsurface, maybe a couple of meters down, but the idea of taking a big heat source, burying it, and putting it near that frozen mud, potentially turning that subsurface into liquid water… You would create a perfect growing environment” for Earth bacteria. That would be bad because Earthlings are supposed to avoid “harmful contamination” of other worlds, and also because if scientists ever want to find out if there’s native life on Mars, we can’t go mucking it up with Earth germs.

Untethered Space Walks

When astronauts on the International Space Station go outside, they leash themselves to the station so they won’t float away. The Martian movie includes a few untethered space walks, probably to add dramatic effect. Yes, there are packs that would let an astronaut jet around without a tether, but NASA doesn’t like to use them. In real life, NASA astronauts have only ever performed a handful of untethered excursions.

Radiation Protection

Because of its thin atmosphere, Mars is pummeled with space radiation that can be harmful to humans. If NASA were planning a long-term stay on Mars, says Lavery, they wouldn’t use the inflatable habitats you see in the movie and the book. Instead, the habitats would probably be placed underground or, if above-ground, covered in Martian soil to protect against radiation. Still, according to Lavery, Mark Watney’s overall exposure probably wouldn’t have been intense enough to cause noticeable health effects during the time period of the story.

What It Gets Right

These criticisms are all minor, and they don’t ruin the movie at all (well, ok, the space walk thing was kind of annoying…). What’s more notable, really, is how much The Martian gets right.

How We’ll (Probably) Get To Mars

Barring any surprising innovations, we’ll travel to the Red Planet in a spaceship that’s built for long-term human spaceflight, land on Mars in a descent vehicle, camp out in pre-delivered habitats eating pre-delivered food, and then go home via a Mars Ascent Vehicle that docks with the same big spaceship we arrived in. Just like in The Martian.

“A lot of that stuff is actually very much in line with what our current thinking is right now about how you might structure a mission to Mars,” says Lavery. On one level, he continues, we know how to get to Mars—we’ve done it several times with robots. But for a human mission, everything from the life support systems to communications technologies still needs to be scaled up and fully developed.

The Little Things

Wearing a space suit is often compared to wearing a giant balloon. The suit is inflated to mimic Earth-like air pressures, but it also makes it really difficult for an astronaut to move, particularly the fingers. It takes a lot of effort to bend the inflated gloves—something Mark Watney complains about in the book.

It’s a known problem and NASA’s looking into it, said David Miller, an MIT aerospace engineer and NASA’s chief technology officer, during the panel. “What we’re working on is how to make gloves that still keep the right pressure on the skin so the blood doesn’t boil, but still allow you to do a lot more work.”

Although direct mentions of these sorts of details clearly couldn’t fit the movie, Weir’s meticulousness shines through in subtle ways.

Real Scientists, Real Astronauts

Unlike most movie scientists, whose job is to pop into a scene and use big words to explain usually unrealistic concepts, the scientists in The Martian seem more like real people with distinct personalities, working together to solve a problem. That’s what pulled screenwriter Drew Goddard into the project.

“I had never read anyone capture scientists the way Andy captured scientists,” said Goddard, who grew up in Los Alamos—a town full of scientists, thanks to the national lab there. “What Andy captured was much closer to my experience of being around scientists, which is the intelligence mixed with the camaraderie, mixed with the humor, that sort of happens when you get a lot of really smart people together to solve a problem.”

Former astronaut Mike Massimino, who also spoke at the Columbia event, says the astronauts in the book and movie were also portrayed accurately. “I’m very excited about the way that the relationships between the astronauts were portrayed,” he said. Between adventure training, survival school, and getting thrown into extreme environments together, astronauts build up a strong bond. “We take care of each other as best we can. When someone needs someone, there’s nothing we wouldn’t do.”

Eventually, S*** Is Going To Hit The Fan

The Martian trailer has Mark Watney saying, “I guarantee you that at some point, everything’s going to go south on you, and you’re going to say, ‘This is it, this is how I end.’ Now you can either accept that, or you can get to work.”

As overquoted as it is, the line makes a good point: no matter how many precautions you take, space is a dangerous place, and stuff is bound to go wrong. Sometimes those problems are fatal. Other times, human ingenuity pulls through.

The Martian is basically MacGyver on Mars, and there’s actually historical precedent for it. If the Apollo 13 astronauts hadn’t been able to use tube socks and duct tape to fix a carbon dioxide filter, they would have died.

“Sometimes you need to use a technology in a need that you did not foresee,” said Miller. “It’s always worth thinking about that in advance.”

There’ve been plenty of space disaster movies. But what’s great about The Martian is that the problems are solved without resorting to incorrect orbitals or “the power of love” (we’re looking at you, Gravity and Interstellar).

In the end, that’s what will likely secure The Martian‘s place in science fiction canon. In 20 or 30 years, when real-life astronauts will supposedly visit Mars, we’ll likely look back on this book and movie without thinking it’s ridiculous. If anything, maybe (hopefully) we’ll laugh at how conservative it was in its estimation of human technological prowess.