PASADENA, Calif. — We’ve seen a brief sample of the full-color environment at Gale Crater on Mars, but before the Mars rover Curiosity can beam back full-size versions, its cameras need a checkup. Scientists want to be sure they’re seeing Mars as it really looks, in real ochre — so the cameras have to be calibrated. To do it, Curiosity will call upon one of the most ancient tools of astronomy: A sundial.

Mars images are stunning to see, but they offer real science value, too, because Curiosity’s science team will use them as their eyes on Mars. Curiosity’s view of the rim of Gale Crater and Mt. Sharp at its center will help the team determine where the rover should drive first, and after that, which rocks will be most interesting to zap with its ChemCam laser or drill with its robotic arm. Determining a rock’s interestingness is largely accomplished by just looking at it, so the view must be accurate, explains Tyler Nordgren, associate professor of physics at the University of Redlands in California.

“[Images] allow you to figure out what the landscape is made of, and what the rock is made of. Part of how you figure out what rocks are made of is by figuring out what color they are,” he says. “It allows you to figure out the history of Mars.”

Curiosity will continue to calibrate its high-resolution, 3-D color cameras later today (or to-sol?) on Mars, NASA managers said at a news conference Tuesday morning.

Mars’ atmosphere is very different from Earth’s — it’s much thinner and it’s full of carbon dioxide, and it lacks the type of tiny aerosols that contribute to the Rayleigh scattering effect on Earth that turns our sky blue. The sun is also far fainter at an extra 50 million miles away. Dust kicked up by Mars’ howling winds fills the skies, much more so on windy days, and as a result Mars’ atmosphere looks slightly pink. This can cast a rosy hue on anything in Curiosity’s surroundings.

Every camera needs a color cue to be sure the images represent reality. If trees on Earth look blue in your image, you can easily tell the color balance is off. But Curiosity doesn’t have any natural color cues on Mars. Everything is pretty much red — “it’s all variations on a theme,” Nordgren says. “You need to determine, when you look at a rock wall or cliff face and it looks red, how much of that is due to the rock, and how much of that is due to the lighting.”

To do this, Curiosity is carrying a 4-inch square plaque mounted near its backside, which will be the first subject for the MastCam cameras. It has four slices of color, representing known shades of blue, red, green and yellow. A little post and ball at the middle act as a sundial that casts a shadow. This way, the rover can tell the right color in full light and in shadow.

Curiosity’s cameras will shoot the sundial with its set of filters. Then it will take science images, ones the team will use to determine likely targets for exploration. Afterward, the cameras might shoot the dial again just to be sure.

“That tells you, under the current lighting conditions that are going on, here’s how we tweak the different images as we put them together, to get the color balance just right,” Nordgren says.

Scientists can then make false-color images, heightening contrast or hue to highlight certain topographical or morphological features of the rocks. They could even take out the sky’s reddish glow, Nordgren says. “Imagine you could transport that section of Mars here to Earth, and have a nice yellow-white light shining on it, as if you were in the lab. Then you could see, ‘Ah, this rock is still red, but it’s not quite salmon-colored, it’s more of a brick color.'”

The image below shows the same calibration target on the Mars Exploration Rover Spirit.

Curiosity’s plaque is the same, except that Nordgren and mission scientists at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory added updated plaques. Curiosity’s sundial is actually a leftover from the MER missions.

“That’s really all you need to be scientific,” Nordgren says. “But we thought, why not use this very dry boring technical piece of equipment, and turn it into something beautiful and evocative?”

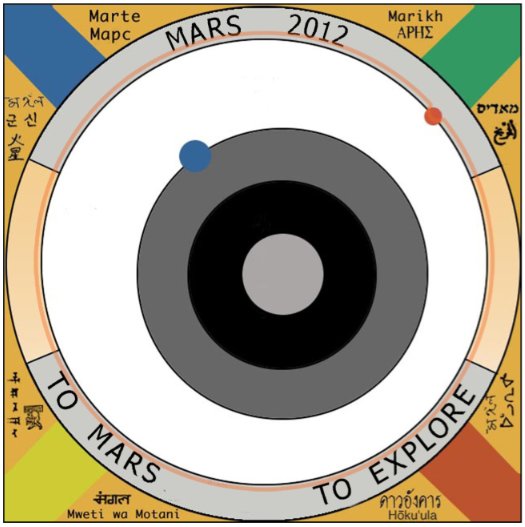

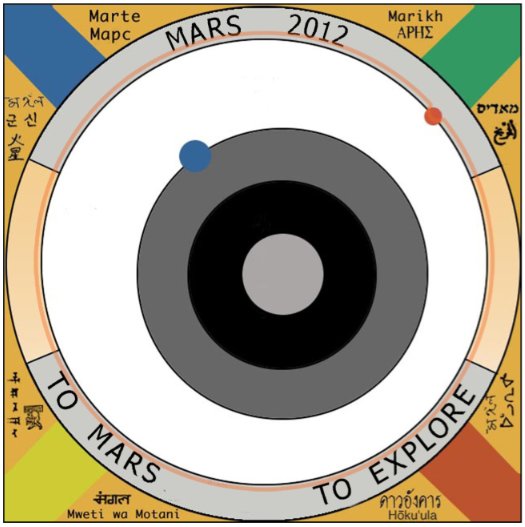

On the target’s face, the name MARS appears in 16 different languages. In the center, the sundial itself represents the sun, and concentric circles surrounding it represent the orbits of Earth and Mars, which are themselves represented by a pale blue dot and a red dot. Each home-plate color slice has a phrase describing what the mission means for human exploration. It reads:

“For millennia, Mars has stimulated our imaginations. First we saw Mars as a wandering red star, a bringer of war from the abode of the gods.

In recent centuries, the planet’s changing appearance in telescopes caused us to think that Mars had a climate like the Earth’s.

Our first space age views revealed only a cratered, Moon-like world, but later missions showed that Mars once had abundant liquid water.

Through it all, we have wondered: Has there been life on Mars? To those taking the next steps to find out, we wish a safe journey and the joy of discovery.”

Every sundial also has to have a date — it’s sundial tradition, Nordgren explains — and a motto. Curiosity’s is stamped “Mars 2012” and “To Mars to explore.”

“It embodies the scientific process. Who knows what we’ll discover with this new spacecraft?” Nordgren says.

Nordgren started building the MER Mars sundials when he was a graduate student at Cornell, studying with Steve Squyres, the principal investigator on Spirit and Opportunity. He builds and collects sundials and is fascinated by them, he says.

“They’re beautiful, they’re precise, they’re amazing works of engineering and art that tie together astronomy and timekeeping,” he said. “People have been using sundials, in one form or another, for thousands of years. I think they’re lovely. It’s a wonderful intersection of 21st century technology and ancient technology, on the surface of Mars.”