Follow all of PopSci’s COVID-19 coverage here, including tips on cleaning groceries, ways to tell if your symptoms are just allergies, and a tutorial on making your own mask.

This post has been updated.

The hunt for pharmaceutical weapons to help beat the COVID-19 pandemic has already produced a few disappointments (and a few nonsensical suggestions regarding disinfectants). Earlier this year, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) Anthony Fauci made a bold statement in support of Veklury, better known as remdesivir, an antiviral designed to combat Ebola.

“The data shows that remdesivir has a clear-cut, significant, positive effect in diminishing the time to recovery,” Fauci said during a meeting with President Donald Trump and other officials.

Today the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved remdesivir as the first COVID-19 treatment for use in hospitals and other health care facilities. Patients 12 years of age and older can be treated with the drug; younger individuals will need special emergency authorization

Still, remdesivir’s road to approval for the coronavirus has been full of clinical twists and expert concerns. Here’s everything you need to know.

What is remdesivir?

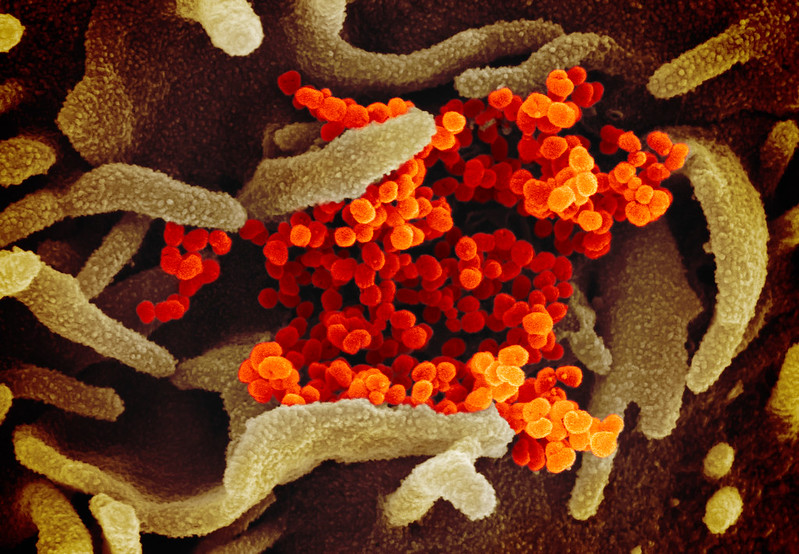

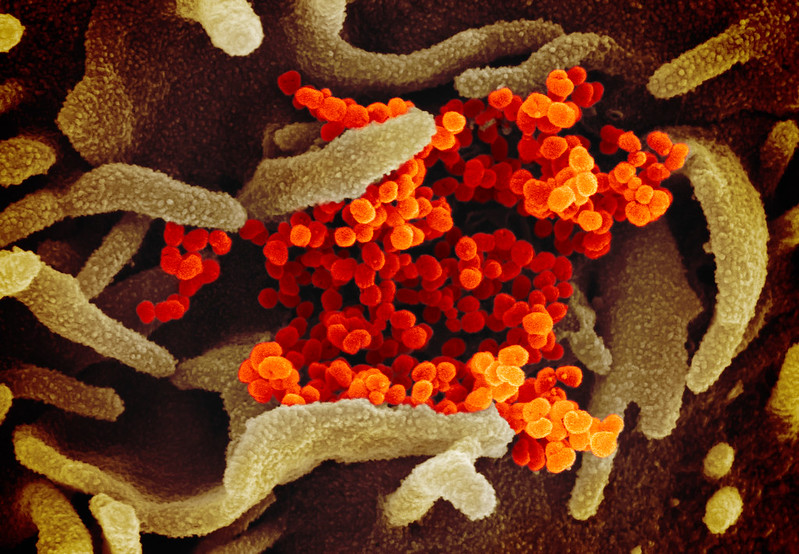

Remdesivir is a drug owned by the US pharmaceutical company Gilead, originally designed to combat Ebola. It’s an antiviral, and works not by killing the virus directly, but by inhibiting its development and replication. According to Stat, the molecule that powers remdesivir was originally tested in the lab on multiple types of viruses, including other coronaviruses like SARS and MERS, with some level of success. Ultimately, Gilead focused on honing its efficacy against Ebola. This process was fast-tracked during and after the Ebola epidemic in West Africa between 2013 and 2016. However, later data showed it to be less effective than other treatments.

As Stat explained back in March, while remdesivir may have quickly fallen out of favor as an Ebola drug, its rapid development for that purpose left it poised to speed into human trials as a COVID-19 therapy: Gilead already had ample data proving that the drug wasn’t dangerous. That, combined with evidence from remdesivir’s early days of development that it might be able to fight viruses closely related to SARS-CoV-2, made it an enticing option for physicians in search of COVID-19 therapies.

How well does remdesivir work against COVID-19?

Only a handful of studies have been conducted so far on the use of the drug on coronavirus patients, and results have been mixed.

Fauci’s praise for the drug referred to an earlier government-sponsored study where around 1,000 COVID-19 patients were treated with either remdesivir or a placebo, with neither the patients nor their caregivers knowing which they received (this is known as a controlled double-blind study). While there was no statistical significance in the small difference in mortality rate between the two groups, remdesivir patients spent less time in the hospital overall: an average of 11 days compared to 15.

A shorter hospital stay means less time spent at risk of developing complications. It also means ICU beds and ventilators can open up to serve other patients more quickly. But the study’s full data wasn’t released to the public or reviewed by other scientists, so it’s difficult to know how these results could be applied to patients in general.

“Am I encouraged from what I’ve heard? Yes, I’m encouraged,” Steven Nissen, the chief academic officer at the Cleveland Clinic, told Reuters. “But I want to get a full understanding of what happened here, and not get it via a photo opportunity from the Oval Office.” Other experts told the press that even if the findings held up to analysis, the positive results of the NIAID trial were less dramatic than they’d hoped for.

Gilead also released the findings of its own study conducted over April and May, which reported positive results. However, this study didn’t compare remdesivir to a placebo—it only tested patients taking either five- or ten-day courses of the drug. That means its data doesn’t prove that remdesivir is more effective than no antivirals or other types of treatments. A third study conducted in China, which focused on patients with more severe COVID-19 than those studied in US trials, reported no significant benefit from remdesivir.

The FDA’s recent decision partially hinged on a new peer-reviewed double-blind study, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, that did test the drug against a placebo. It showed similar outcome to the government report from the spring, with shortened hospital stays on the 521 patients treated with remdesivir. It’s also worth noting that President Donald Trump received the medication while infected with the virus at the beginning of October.

But even if remdesivir does prove useful in the fight against this pandemic, it won’t eliminate the disease or the need for ventilators. Antivirals are most effective when taken early, when they can keep a virus from replicating widely through the body, and remdesivir is administered intravenously—so while it may have some effect, it will likely only be used on hospitalized patients, who may only stand to benefit marginally from the therapy. The drug could make a life-saving difference for some patients; it could even help enough people to make the pandemic significantly less deadly. But it won’t save everyone.

“It is very important to understand that remdesivir and antivirals in general are not silver bullets,” Aneesh K. Mehta, an investigator at the remdesivir trial site at Emory University, said at a press conference. “They do not immediately get rid of an infection. They work by slowly preventing the virus from making more of itself.”

What happens next?

The FDA’s approval of remdesivir should trigger an uptick in production of the drug. Gilead had already pledged to donate more than 100,000 courses to the US government when it got Emergency Use Authorization for the treatment back in May, which allowed physicians to use it on COVID-19 patients without the usual process of clinical trials. At the time, Gilead Sciences chairman and CEO Daniel O’Day told CBS that the US government would be in charge of allocating distribution of remdesivir based on where case counts were highest and where hospital ICUs were under the most strain. The company didn’t disclose any numbers around its current stock after today’s FDA update, but did state that the drug will continue to be made widely available in hospitals across the country.

Meanwhile, many researchers—including some of those who worked on the latest remdesivir trials—are continuing to look for other, more effective therapies.

Studying the efficacy of a new drug takes time and lots of carefully collected data, which is even more complicated when the disease being treated is as poorly understood as COVID-19. It’s possible that the US won’t know for certain how effective remdesivir is for the general public until the next wave of the pandemic has passed. But for now, the antiviral—while certainly no silver bullet—does offer some hope.