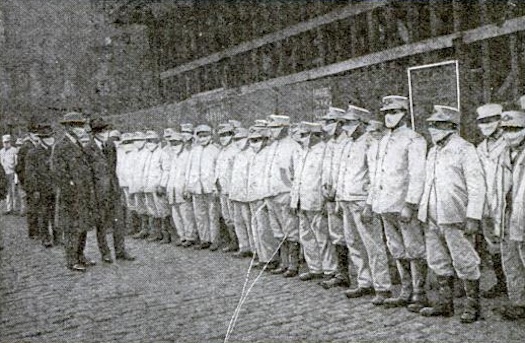

Every flu season is a deadly flu season. Though this year may feel worse than usual—and may end up being deadlier—it’s also a grave reminder that influenza always kills people. We’re just sometimes more aware of it.

For the many thousands who contract the flu and recover, it may seem unfathomable that you could die from what often feels like a particularly nasty cold. Well, this is how:

Step 1: Be very old or very young, probably

The immune system of an eight-month-old and a eighty-year-old are similar in that they’re not well-equipped to handle the flu. Infants (and even young children) simply haven’t been exposed to enough pathogens for their bodies to know how to fight off viruses, and the elderly suffer from general deterioration of the systems that would normally kill influenza. This is why most of the people who die from the flu aren’t healthy twenty-somethings or even parents—they’re either very young or very old.

But this isn’t to say that twenty-somethings don’t die from influenza. They absolutely do. It’s just that they’re less likely to die from most strains of the flu. This isn’t always true; the Spanish Influenza targeted healthy young adults because they’d never before been exposed to a similar strain. And this year’s virus seems to be harder than usual on baby boomers (many of whom are still too young to be the flu’s primary targets) because it’s dissimilar from the strains they were most exposed to as children. In other words, no one is guaranteed to get the flu or not get it. But in general, the very young and very elderly need the most protection.

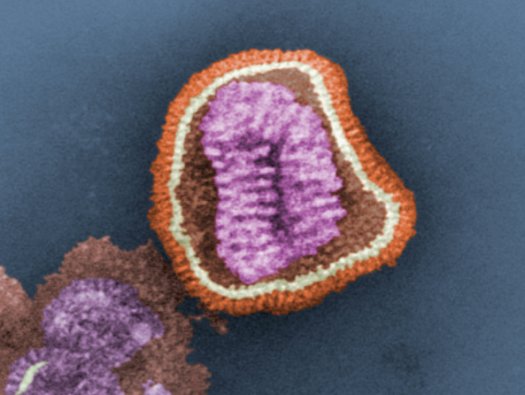

Step 2: Develop lung inflammation

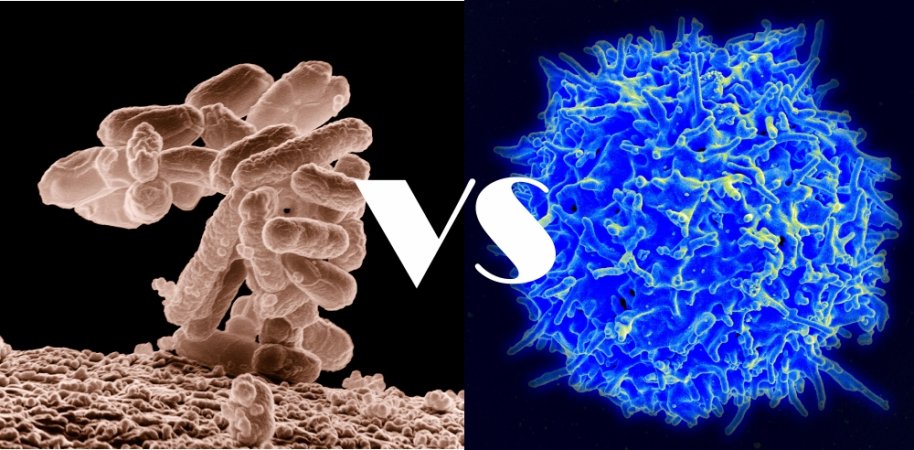

As white blood cells of various types hunt down the flu virus within your body, they bring inflammation along with them. Inflammation is an immune reaction to all kinds of problems, from viruses to bacteria to physical trauma, and it’s meant to heal you. Skin and organs swell a bit to accommodate all the new cells rushing in to try to repair your body. This isn’t a problem for small infections, but too much inflammation can be dangerous.

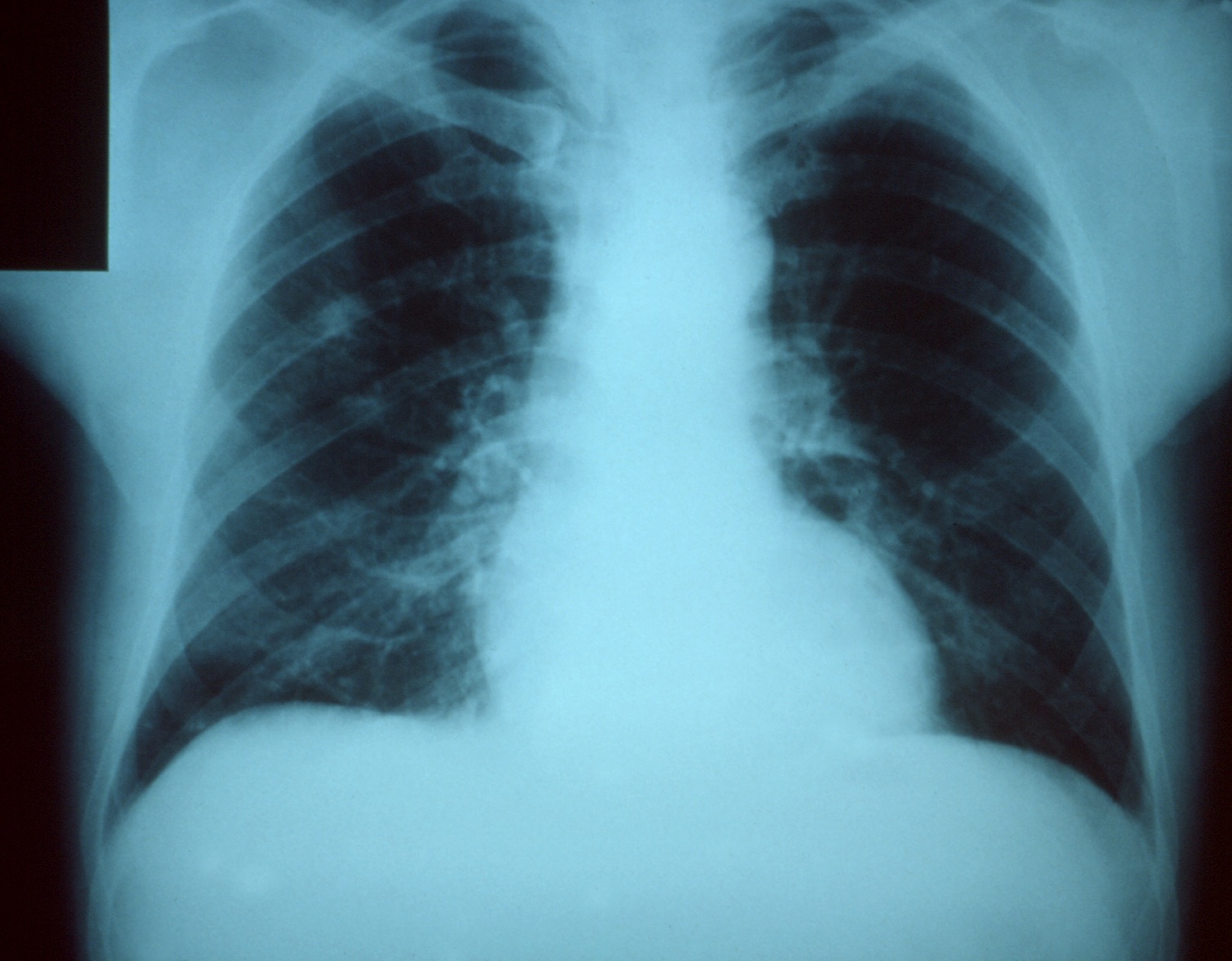

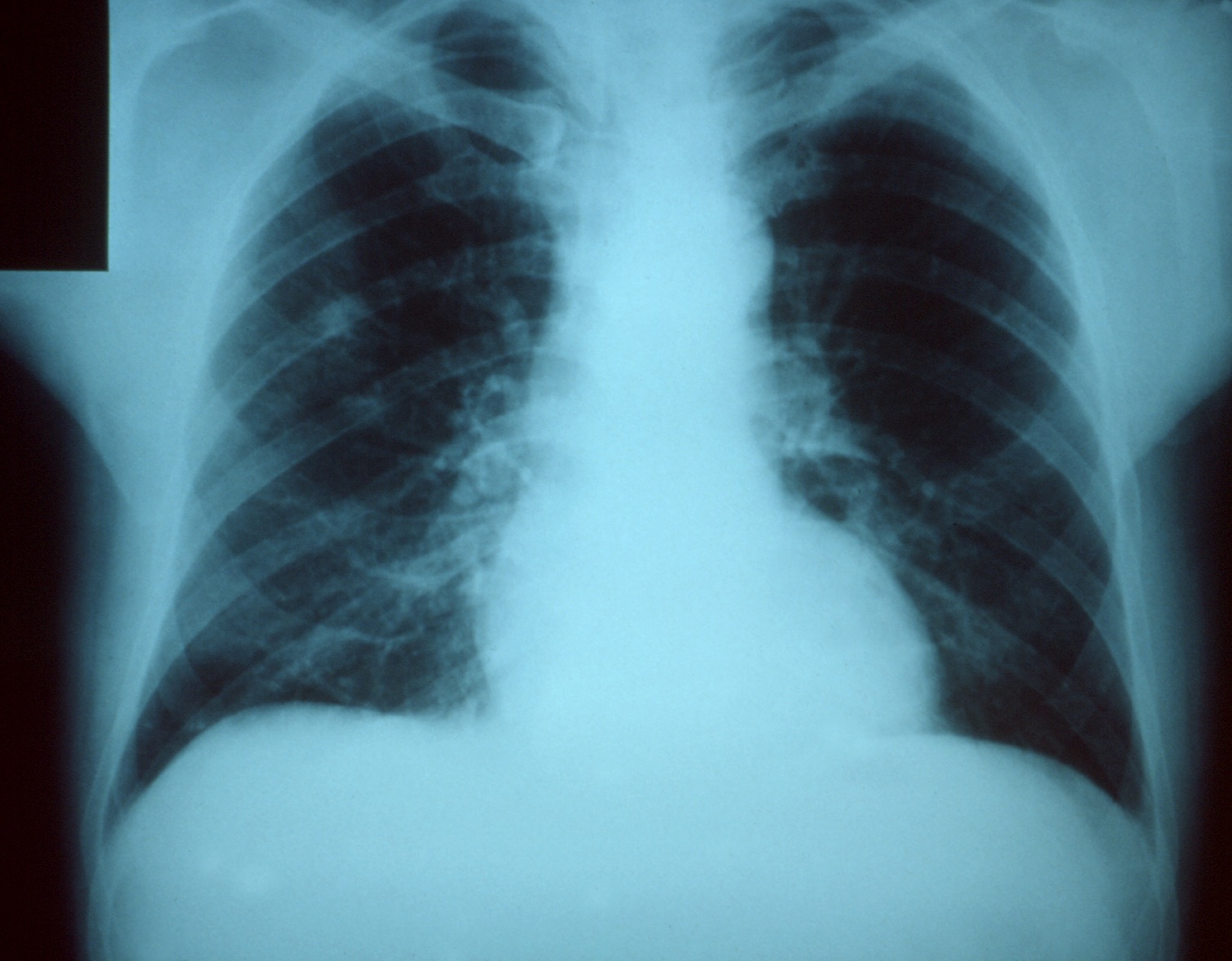

In the lungs, for example, swelling can prevent oxygen from reaching your blood vessels. Oxygen normally moves across very thin membranes in endless moist chambers inside the lobes of your lungs. When that tissue becomes swollen with immune cells, it’s much harder for oxygen to reach the tiny blood vessels that it’s supposed to move into. There’s also some degree of damage to the lung tissue. Viruses can’t replicate by themselves, so they have to do it inside your cells instead. That means that in order to kill the virus, your immune system has to destroy your body to some extent, which only makes oxygenation harder.

About a third of people who die from the flu do so directly. That is, they die from the effects of the virus (and the effects of their bodies trying to fight it off). Respiratory failure—when your lungs simply can’t get enough oxygen—is one of the most common ways. It’s also one of the fastest. Direct deaths from the flu occur quickly, often within a few days, and with little warning.

And that’s not the only way inflammation can get you.

Step 3: Have body-wide inflammation, otherwise known as sepsis

“Multiple organ failure” is just as bad as it sounds. Just like inflammation in the lungs, your other organs can also develop severe swelling as your immune system sends cells out to kill the virus. A body-wide reaction like that triggers sepsis, which is when your immune system essentially reacts so strongly that the resulting inflammation overwhelms your organs. Multiple organs can shut down at once, and death is swift.

Even inflammation in individual organs can cause serious side effects.

The heart and brain are especially vulnerable to inflammation, since they have to function properly all the time in order for you to stay alive. They can’t tolerate damage the way kidneys or livers can. Brain inflammation quickly leads to death, and even if swelling in the heart doesn’t immediately cause death, it can trigger other, latent cardiac problems to flare up.

If you survive all that, there’s still one more danger left to go.

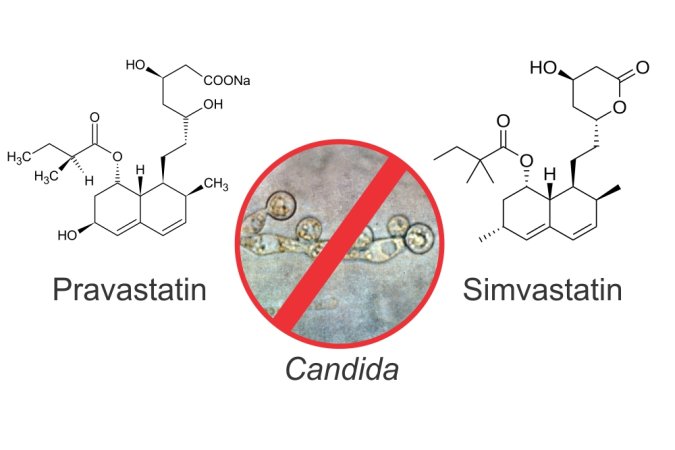

Step 4: Acquire a secondary infection, most likely pneumonia

We all have bacteria inside our bodies, most of which do us no harm (and many of which do us a lot of good). That includes otherwise dangerous bacteria that exist in small quantities or are sequestered away such that they don’t hurt us.

But when your immune system is already flagging under the weight of a viral infection, those bacteria can spread to the lungs and take hold. This is called a secondary infection, and when it occurs in the lungs we call it pneumonia. Unlike a direct death, secondary pneumonia acts more slowly. Often you’ll start to feel better after a few days with the flu virus as your body starts to fight it more effectively. And then, suddenly, you’ll feel a lot worse. The bacteria have bided their time and are now multiplying rapidly inside your lungs, and your already exhausted immune system is struggling to keep up.

If you don’t report to a hospital when you start to take a downturn, you’ll likely die from the infection. Antibiotics can help if you catch it in time, but they’re no guarantee. Sometimes the bacteria have already spread so much that the antibiotics can’t kill them fast enough. And organ damage doesn’t necessarily reverse as soon as you’re being treated.

If you or someone you know has the flu—or just thinks they might have the flu—and you suspect they’re taking a turn for the worse, please go to the doctor. Influenza kills thousands of people in the U.S. every year. Don’t wait until it’s too late.