If someone offered you a drug that would save your life, what would you be willing to pay for it? Could you even put a number on it?

Let’s start at $750 per pill. It’s a large number, but when you consider its benefit — your health — it certainly seems manageable. And think about what else that number buys. Along with curing you, that money pays for scientists who will design even better drugs, which might work faster and have fewer side effects. What’s more, your insurance provider or Medicare might cover much of the bill.

Now imagine, after being quoted that price, you heard a neighbor with the same illness only paid $13.50 per dose last week. What do you think of that $750 figure now? Does it seem wildly unfair? Who decides these numbers, anyway?

This is the situation that set up a major firestorm this week over drug prices, with a company called Turing Pharmaceuticals at the center. Turing Pharmaceuticals is a startup operated by a former hedge fund manager, Martin Shkreli (who is no stranger to controversy).

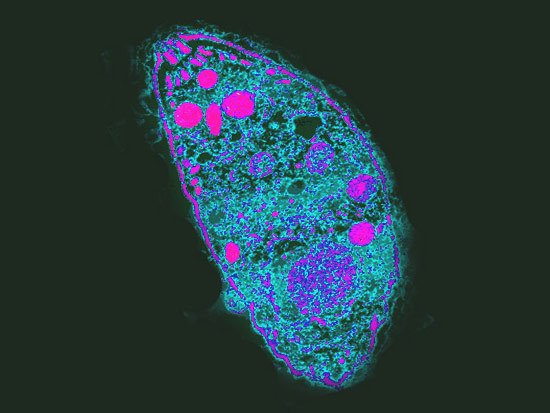

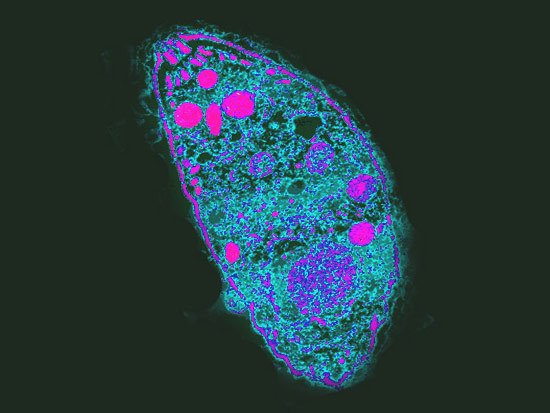

Last month Turing purchased the intellectual property right to a drug developed in 1953 called Daraprim (also known by its scientific name, pyrimethamine), which treats a parasitic disease called toxoplasmosis. You might recognize that as “crazy cat-lady syndrome,” because it can be transmitted through cat litter, among other ways.

It can cause blindness, neurological problems and even death, but is easily treated with a six-week course of Daraprim taken twice a day. That treatment used to cost about $1,130. After Turing bought the drug in August, treatment shot to $63,000, according to a joint statement from the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the HIV Medicine Association. The statement pointed out that for some vulnerable people like AIDS patients (who often take the drug as a preventative measure), annual treatment would now be $634,000.

When the news hit major media outlets, outrage spread across the web, with many members of the public and journalists calling for Shkreli to lower his company’s price. After a couple days of raging debate, Shkreli told news stations Tuesday night that the company would indeed bring the cost down, but he hasn’t said to how much yet.

“There were mistakes made with respect to helping people understand why we took this action; I think that it makes sense to lower the price in response to the anger that was felt by people,” Shkreli told NBC News.

But this debate is about much more than Daraprim. Some drugs are just astronomically expensive, including lifesaving treatments for cancer, hepatitis C, and other ailments. It’s such a common problem that medical societies offer tips to help doctors get drugs for their patients. There’s an entire cottage industry of Patient Assistance Programs that offset the cost of certain drugs, operated by private foundations and some drug companies. Doctors, patients, and pharmaceutical companies have been arguing about this for years, but in recent months it’s been getting more contentious as prices have been on the rise. Pharmaceutical prices were up 13.6 percent last year, compared to about 8 percent over the previous five years, according to Topher Spiro, vice president for health policy at the progressive-leaning Center for American Progress.

“There was a big spike last year, and I think that’s what’s fueling a lot of the current debate. It’s increasing health insurance premiums and Medicare premiums,” Spiro told Popular Science. “A big portion of the premium rate [insurers] are seeking is a direct result of pharmaceutical costs, so it is starting to explode.”

In August, for example, 117 doctors from around the country signed a commentary in the journal Mayo Clinic Proceedings calling for a complete overhaul of cancer drug prices. In 2014, all new FDA-approved cancer drugs were priced above $120,000 per year, the doctors pointed out. It’s a situation that literally leaves people choosing between paying their mortgage and paying for their lifesaving cancer drugs.

The Mayo Clinic Proceedings letter recommends allowing importation of cancer drugs across the border; laws that prevent companies from delaying access to generic versions of their drugs; letting Medicare negotiate drug prices; and even forming price oversight committees that would review new drugs and propose prices based on their potential benefit.

“The good news is that effective new cancer therapies are being developed by pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies at a faster rate than ever before,” the letter reads. “Drug companies should be rewarded with reasonable profits for these efforts. The unfortunate news, also acknowledged by some of the pharmaceutical leadership, is that the current pricing system is unsustainable and not affordable for many patients.”

As the Turing price-test showed, this is hardly limited to cancer. Members of Congress (including Sen. Bernie Sanders, the Vermont independent vying for the Democratic presidential nomination) earlier this summer sent a letter requesting data from a company called Valeant Pharmaceuticals after it raised the prices of two heart medications. Isuprel and Nitropress went up by about 525 percent and 212 percent, respectively, immediately after Valeant bought the drugs from Marathon Pharmaceuticals. Before the sale, Marathon itself had already jacked up the prices by nearly 400 percent over their 2013 cost, according to Sanders’ office.

“It is unacceptable that Americans pay, by far, the highest prices in the world for prescription drugs,” he said in a statement.

Doctors who have cried foul have pointed out that the Turing price hike would actually mean fewer patients can access Daraprim. Dr. Wendy Armstrong, professor of infectious diseases at Emory University in Atlanta, told The New York Times her hospital has not had access to the drug in several months and that toxoplasmosis was not a disease where physicians have been crying out for better therapies. Spiro said many drugs like Daraprim are simply being marketed differently with little or no change to the way they work.

Pharmaceutical companies are quick to point out that the promise of profits is part of what sparks innovation in the first place. And some of their revenues are re-invested in research and development, they add. It takes about 10 years for a new medicine to reach the marketplace, including about seven years for clinical trials, according to PhRMA, the main trade group for drug industry. PhRMA says a new drug costs about $2.6 billion to develop.

“Conversations on the cost of medicines often fail to acknowledge the competitive biopharmaceutical market that exists in the U.S., which helps to control costs while encouraging the development of innovative new therapies,” Holly Campbell, a spokesperson for PhRMA, told Popular Science.

In some cases, new and very expensive drugs are indeed better therapies for which people have been clamoring for some time. One notable example is Sovaldi, which cures the liver-wasting disease hepatitis C. In 2014, the pharmaceutical company Gilead Life Sciences came under fire for charging about $84,000 for Sovaldi (a Best of What’s New winner). It cures hepatitis C in three months with practically no side effects.

When I talked to John McHutchison, Gilead’s vice president of clinical research, he said Sovaldi took years and considerable effort to develop because it’s a very precise, targeted virus attacker called a nucleotide polymerase inhibitor. Instead of working with the immune system, like many other drugs, Sovaldi works against the hepatitis virus, attaching itself to the mechanism the virus uses to replicate. Its developers had to find just the right enzymes to make it work without harming other cells in the body, McHutchison explained to me last year. Gilead also notes that most people who need Sovaldi can get it at deep discounts through insurance companies.

Sovaldi was one of the first high-priced drugs to hit the market, and other companies have followed suit, Spiro said.

“It happens to be a coincidence that a lot of these drugs are coming onto the market now. Some of the newer ones cost $10,000 a month. We’re seeing a lot of new drugs that cost thousands of dollars,” he said.

This is not to say that it ought to be this way, and that insurance companies (and taxpayers) should be on the hook for pricey treatments. The Mayo commentators argue that high prices don’t help anyone, noting that money diverted as profit doesn’t necessarily contribute to better health outcomes or novel therapies. Given this climate, the Mayo co-signers said there is “no relief in sight” because drug companies keep challenging the market by raising prices higher and higher. “This raises the question of whether current pricing of cancer drugs is based on reasonable expectation of return on investment or whether it is based on what prices the market can bear,” they wrote.

But the market didn’t even have a chance to bear a $750-per-pill treatment for toxoplasmosis, as Turing Pharmaceuticals learned. The people would not go for it. Might that mean people are ready for some kind of price cap, or at least a new type of regulation? The Mayo cosigners call for a few incremental steps in that direction. In a new report for CAP, Spiro and his coauthors also call for new executive actions and congressional legislation to address costs. And the Democratic presidential contenders are beating this drum, too.

Former secretary of state Hillary Clinton’s plan includes a per-patient spending cap, a requirement that drug makers spend a certain percentage of their profits on research and development, and a way to enable Americans to import drugs from other countries. Sanders’ plan, announced earlier in September, also calls for importing drugs from Canada and for allowing Medicare to negotiate drug prices, something that was expressly barred under the law that created Medicare drug benefits. The Republican contenders have been much less specific (although Donald Trump did say the Turing price increase was “disgusting”).

Unsurprisingly, the pharmaceutical industry is skeptical. “The policy proposals they recommend would, if adopted, send a chilling signal to the marketplace that risk-taking will no longer be rewarded, stopping innovation in its tracks and halting decades of progress in cancer care,” PhRMA said in response.

Regardless of who wins the White House next year, any sweeping changes would take Congressional action. That means it could be years before any meaningful change takes place, if it ever does — but, Spiro says, that doesn’t mean things can’t get better.

“You could bring public pressure to bear,” he said, “and we’ve seen already how that can be effective. Public shaming is a very effective strategy, and again, there’s no congressional action needed.”

At least it seems to work some of the time.