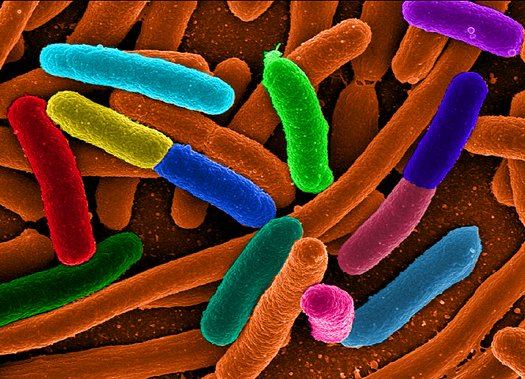

The microbiome—the collection of bacteria and other microbes that reside in our bodies and on our skin—has huge potential. Over the past decade or so, we’ve found that our microbial makeup influences everything from acne to food allergies, obesity, and digestive diseases. But so far, there hasn’t been much research on exactly what strains of bacteria do what, and how much of an influence these microbes can have on us. Are they the determining factor in the development of some diseases, or just a minor player? Even if we figure all these things out, scientists still haven’t found a way to keep the bacteria alive in our guts without continuing to administer them in the form of a pill.

If we can figure these last few pieces out, we might be able to use certain bacteria in a therapeutic way. But we aren’t quite there yet. Most of the probiotics available in pharmacies and grocery stores aren’t really doing much for you. Aside from a select few, these supplements haven’t gone through the same types of clinical trials that prescription drugs must pass in order to prove their efficacy.

But in a study out this week in the journal mSphere, scientists showed that when they gave breastfeeding infants a certain strain of bacteria (commonly found in babies’ guts) for almost a month, those newborns were able to keep the bacteria strain alive for months afterward.

Baby microbiomes are extremely important. Our bacterial diversity is at its most vulnerable during this stage. The microbial colonies that take hold during our first few months and years set the tone for the rest of our lives. Certain factors—like a cesarean birth versus a vaginal delivery, antibiotic use, and formula versus breastfeeding—appear to throw this system out of whack, potentially putting individuals at a higher risk for certain diseases later in life.

But researchers theorize that if they can intervene early and fix the developing microbiome, they can help prevent certain diseases. That presents the last big challenge: What exactly is “normal” microbiome?

Gut microbes are highly dependent on diet, and that depends on a multitude of factors (culture, location, and personal preference, to name just a few). Even diets high in fruits and vegetables will create microbiomes that reflect the type of produce and veggies eaten. There might be no such thing as a “normal” microbiome. Even if scientists can figure out how to hack a human’s gut microbes to replace the flora with something healthier, it’s unlikely to be administered as a single, on-size-fits-all therapy. Certain guts may simply need certain bugs.

But according to study author Mark Underwood, a neonatologist at the University of California, Davis’ medical center, many scientists agree that high numbers of Proteobacteria (a big group including both beneficial species and strains that can cause disease, like E. Coli and Salmonella) put babies at risk for allergies and other types of autoimmune diseases, as well as obesity and diabetes. But high and diverse numbers of commensal bacteria, ones that are found in most adult guts, can lead to better growth, and even better responses to vaccines.

Researchers gave infants a subspecies of a typical bacterial strain, Bifidobacterium longum, for three weeks. (The subspecies is called Bifidobacterium longum subspecies infantis.) They regularly tested their poop for six months to see if the bacteria were actually able to take hold in the gut. They were still thriving even six months after the treatment.

This isn’t what usually happens in adult guts, says Underwood. In fact, he can only think of one study, out in 2016, that showed some adults could maintain foreign bacteria in their guts after stopping the probiotic supplements that delivered them. But infants have gut microbiomes and diets that are much simpler, Underwood says, making them easier to manipulate.

“We hypothesize that this will have a long-term impact on the immune system, even decades later,” he says.

This could be useful for infants at risk of particularly unhealthy microbiomes. During the study, the researcher looked at two different subgroups: One group born through vaginal deliveries and the other through cesarean, which can disrupt an infant’s microbiome. According to Underwood, the two groups’ microbial colonies were different at the outset. However, after they were all given the same bacterial strain, the group born via cesarean section developed microbiomes that more closely resembled vaginally-delivered newborns. “The probiotic was able to eliminate the differences inherent to c-section delivery,” says Underwood.

While this is all quite exciting, Underwood says one big question still remains: How much of an influence do changes in baby gut bacteria have on our potential to develop disease? He hypothesizes that tweaks made to the microbiome could have a long-term impact on the immune system, potentially for decades. But to know for certain, Underwood would have to follow those kids (as well as subjects who didn’t get the probiotic treatment) throughout their lives, and observe what diseases, if any, they develop.

Scientists will also need to do more of these long-term comparative studies to truly understand what constitutes a healthy or unhealthy microbiome, and how much being born via cesarean section or being formula fed can actually influence our gut flora. Further, if the ultimate goal is to use bacteria as a sort of medicine, they need to remain in the gut for a significant period of time, perhaps indefinitely. This study suggests that babies might have microbiomes that are prime for reseeding, but the adult gut will no doubt be even more difficult to cultivate.

While most probiotics are basically useless, there’s still at least one foolproof way to foster a good gut microbiome. More and more research suggests that a diverse colony of microbes is key, and doctors say the best way to get variety in your gut is to eat tons of fiber. Maybe one day we’ll be able to plant the beginnings of a perfectly healthy microbiome into each and every newborn. But for now, we should all just eat plenty of fruits and vegetables.