Plenty of planetary research suggests that Mars was once flowing with water, even if it has none today. But why Mars couldn’t hold on to its lakes and reservoirs, yielding its current dry and rocky terrain, is still an open question—though new research suggests it has to do with size.

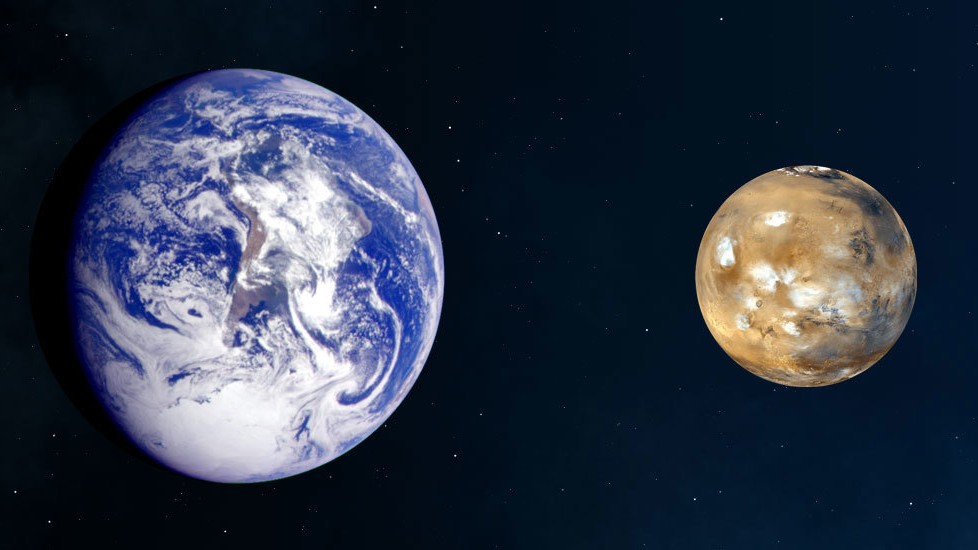

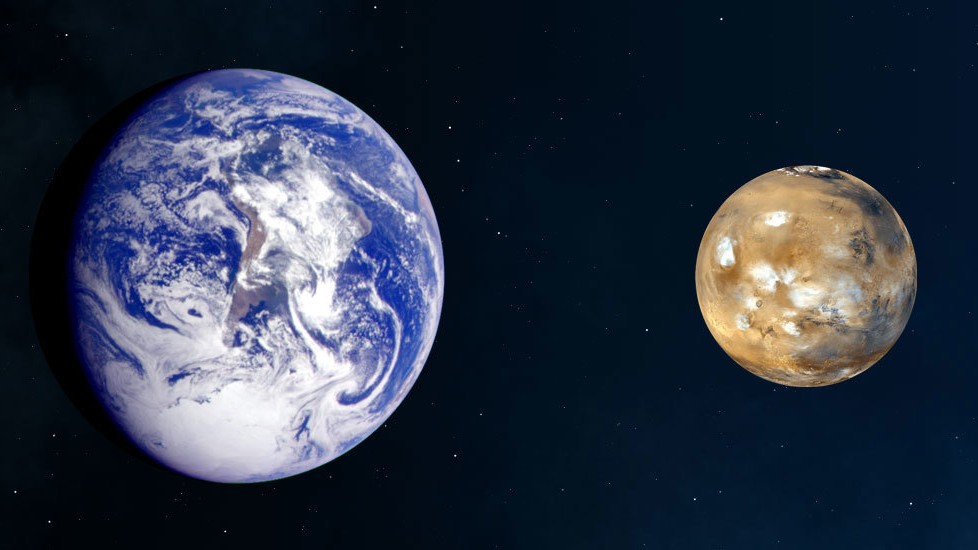

Mars is a pretty small planet. It’s diameter is just over half that of Earth, and it has only about one tenth of our planet’s mass. Because of its compact body, Mars may have never stood a chance at keeping its watery surface. New research shows that Mars’s small size and weak gravity made it easier for water to escape the planet’s thin atmosphere and run away into space. The findings were published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“Mars’ fate was decided from the beginning,” said Kun Wang, a planetary scientist at Washington University in St. Louis and the senior author of the paper, in a statement. “There is likely a threshold on the size requirements of rocky planets to retain enough water to enable habitability and plate tectonics, with mass exceeding that of Mars.”

The research team examined 20 Mars meteorites and looked at volatile potassium levels. That’s because potassium isotopes can act like a “tracer” to indicate how water likely reacted on the planetary surfaces. The meteorites they examined ranged from 200 million to 4 billion years old. Analyzing meteorites with these different ages allowed them to see how potassium levels, and water levels by proxy, changed over time. They found that when our solar system was forming, Mars lost its elements at a faster rate than Earth, but at a slower rate than our moon.

[Related: After a few hiccups, NASA’s Perseverance begins its main missions on Mars]

Wang told NPR that the team’s data showed this trend even in the oldest of the meteorites, signaling that Martian water started depleting almost immediately. Some water on Mars did stay long enough to carve out canyons and river beds, he added. But that likely only lasted for as long as it did because of freezing, as the red planet’s atmosphere cooled.

The new findings could assist future astronomers in their search for life. If planet size can reliably predict the presence of water, then that could help planetary scientists quickly and easily rule out unlikely candidates.

“The size of an exoplanet is one of the parameters that is easiest to determine,” Wang said in a statement. “Based on size and mass, we now know whether an exoplanet is a candidate for life, because a first-order determining factor for volatile retention is size.”

“This does probably indicate a lower limit on size for a planet to be truly habitable,” Bruce Macintosh, deputy director of Stanford University’s Kavli Institute for Particle Physics and Cosmology, told NPR. “Understanding that lower limit is important—there are lines of evidence that small planets are more common than big ones, so if the small ones are dry, then there are fewer potentially habitable worlds out there than we thought.”