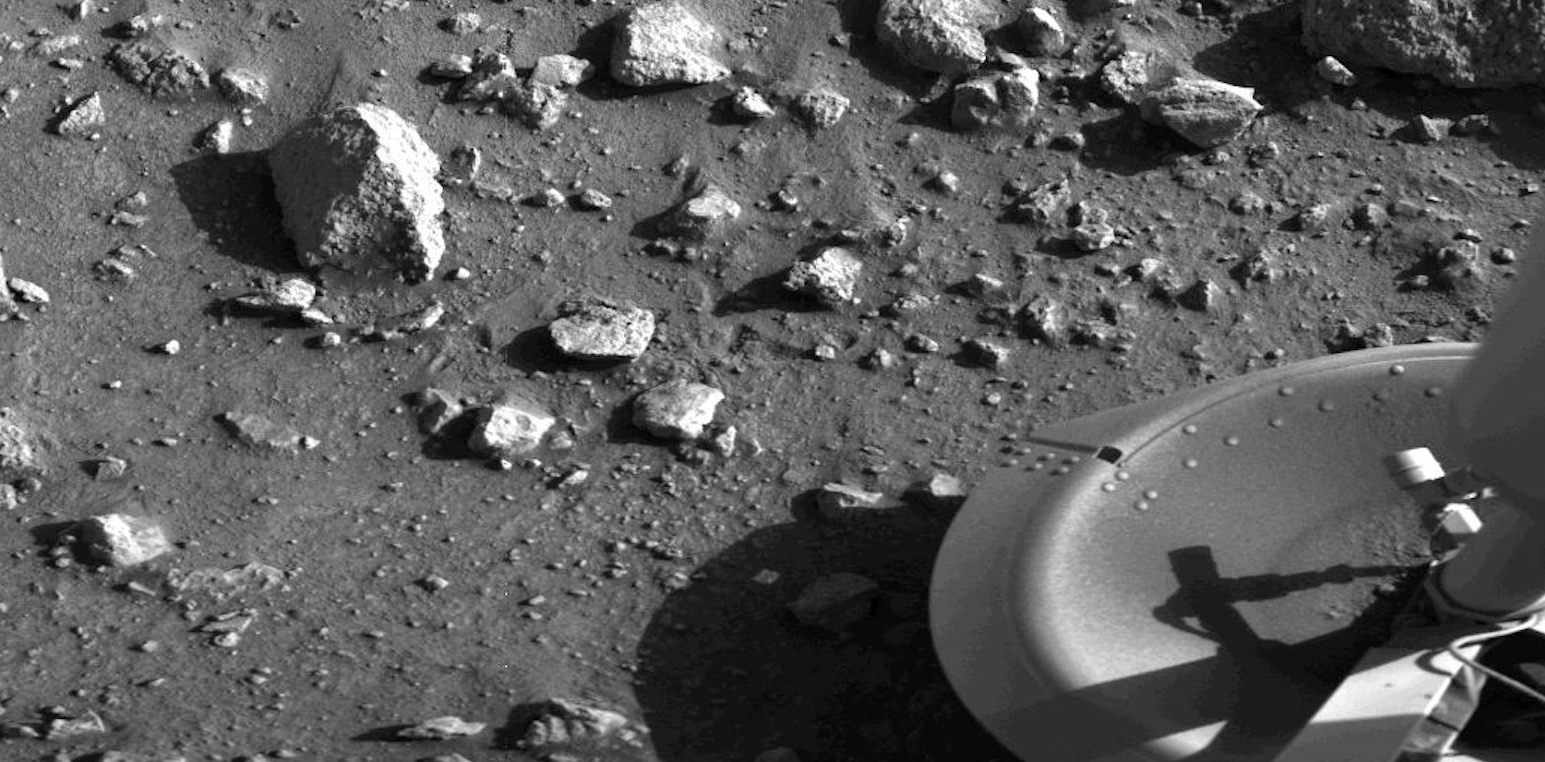

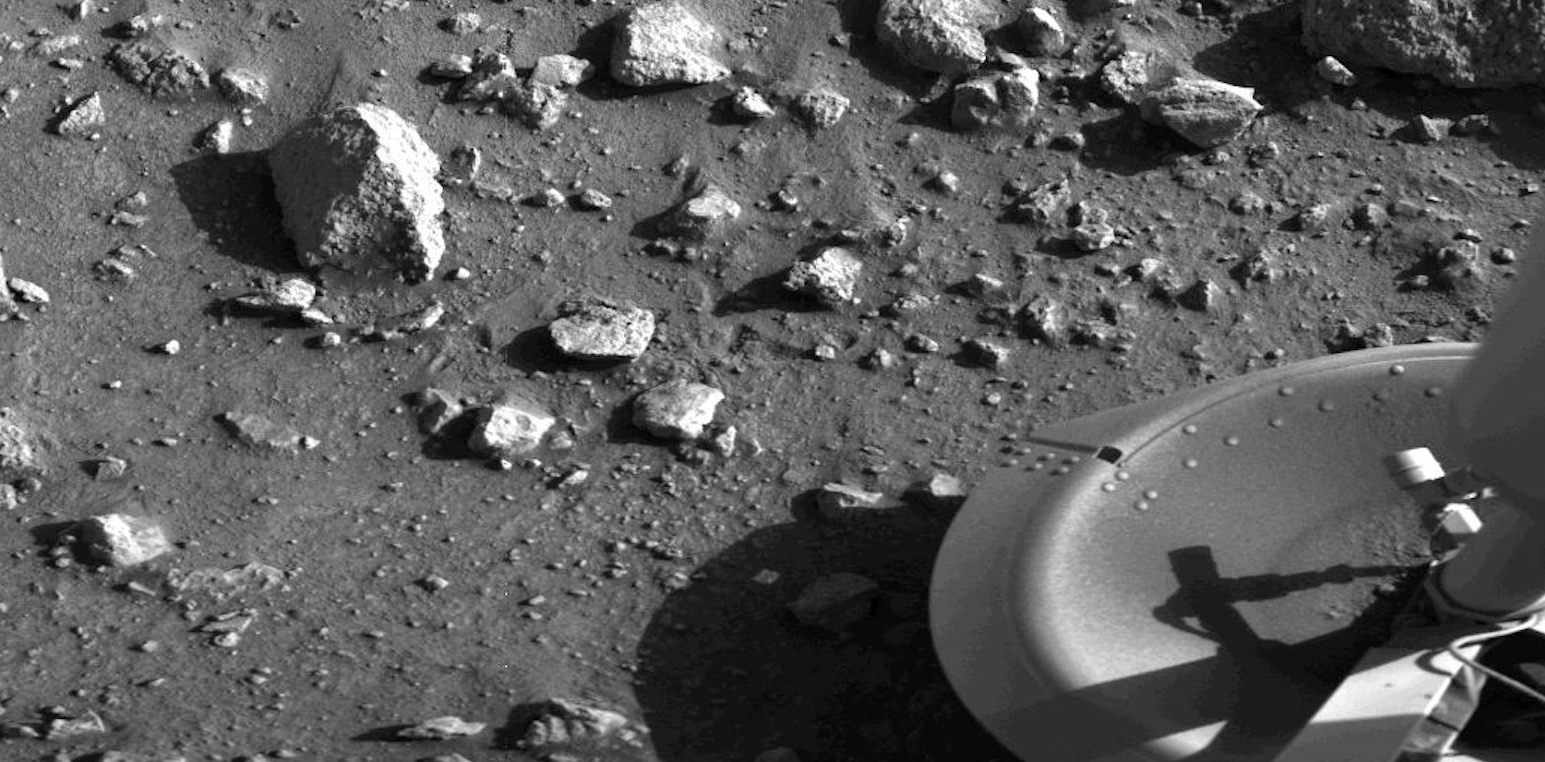

Mars at midday. Or, rather, mid-sol. Welcome to Chryse Planitia, as humans first saw it 40 years ago today, when the first robot from Earth landed on the Red Planet. Viking 1 was supposed to land on July 4, the bicentennial of the Declaration of Independence, but its original landing site was too rocky. The probe orbited Mars a while longer until its human managers could find a flatter, safer spot, and this is the one they came up with.

On the very same day seven years prior, humans had landed on the moon, another feat that also remains astonishing. Think about that: In less than a decade, people went to the moon and sent a robot to Mars, and we saw video of the surfaces of two alien worlds for the first time.

The ever-forward-thinking editors of Popular Science weren’t content to just marvel at the landing — they wondered how long it would take to find life there. Surely, it would be any day now, according to the magazine’s consulting editor for space, Wernher von Braun (yes, that one). His cover story in the July 1976 issue imagined what Viking would find, which previous Mars missions, including the Mariner 9 orbiter, could not.

“Mariner 9’s photos of the Red Planet’s surface, magnificent as they were, couldn’t have revealed a herd of 10 million elephants crossing the scene,” he wrote.

This is so absurd now that it’s funny, because as far as we know, Mars died a very long time ago. There are definitely no elephant herds. But back then, we really didn’t know! Mars could have had elephants, or beavers, or green-faced bipedal aliens trying to broadcast signals to extramartian life the way we look for extraterrestrials. We needed to send robots there to find out.

Even as Viking sent photos like these home to Earth, scientists were eager for more. Carl Sagan, who also would not rest on his laurels, wrote a month after the landing that what we should really do is send cars. “A Viking Rover could be set down in a relatively safe place on Mars and wander to more dangerous and more interesting places,” he wrote in the New York Times. “Over the course of its lifetime it could travel many hundreds of miles. Every day there would be new Martian vistas radioed back to Earth by the rover’s cameras.”

Forty years later, we actually do this, every day, with two separate rovers called Curiosity and Opportunity. Their odometers haven’t hit the hundreds-of-miles mark yet, but the rovers continue to send color images of the Red Planet so frequently that they are routine, and even NASA doesn’t announce them anymore. The only disappointing thing is that while we’re very good at sending rovers and landers, after almost five decades of experience we are nowhere near sending humans.

And yet. We have hovercrafts dropping cars on Mars, probes dropping exploration dinghies onto the surface of comets, a sentinel whizzing past Pluto, Voyagers leaving the solar system, and a cartwheeling armored space tank swinging around Jupiter.

How lucky we are to be alive right now!