Six months after its touchdown in February, having completed a battery of preliminary tests, the Perseverance rover is finally diving into the mission’s science.

NASA announced on August 6 that the rover had tried to take its first rock sample—but as often happens in science, things didn’t quite go as planned. A week later, a chief engineer wrote that the sampling failed because the rover drilled some unexpectedly crumbly material. But Perseverance will, well … persevere; it still has 42 sampling tubes to go.

Getting up and flying

Over the months, Perseverance has had to complete an enormous number of system tests after the team released this “animal into its native habitat,” says Jim Bell, a planetary scientist at Arizona State University who led the Mastcam-Z project, the zoomable camera on the front “mast” of the Perseverance rover. Bell has worked on all five of NASA’s Mars rover missions.

The Mastcam-Z team began by checking the rover’s cameras and vital systems. “The first thing you want to do is look around,” Bell says. These tests are difficult because “everything has got to come through this narrow little straw of data, getting it back to the Earth.”

Once up and running, the piggybacked, first-of-its kind Mars helicopter, Ingenuity, separated from Perseverance. Ingenuity made its successful first flight on April 19 and completed its twelfth flight just a few days ago. The tiny chopper has snagged aerial photos which include a selfie of Perseverance and shots of the same terrain from different angles, which allow 3D mapping of the Martian surface.

[Related: Marsquakes reveal the red planet is way more radioactive than we thought]

“We took a month out of our primary science mission to support the helicopter,” Bell says. That was a tradeoff for the amount of science the main mission can accomplish, but “I think the payoff is going to be great,” he says.

Ingenuity has been surveying the landscape from above, traveling alongside Perseverance, but recently peeled off toward the South Séítah region, cutting across some dunes that would be perilous for Perseverance’s wheels.

“The helicopter is really kind of a separate mission of its own now,” Bell says.

Finding (or making) water and air on Mars

In its first six months on Mars, Perseverance has also successfully produced oxygen with an instrument called MOXIE. The tree-like machine sucks up carbon dioxide from Mars’ very thin atmosphere and breaks it down into oxygen and carbon monoxide. The experiment serves as a kind of proof of concept for future human missions, which will need to produce oxygen for breathing and refueling rockets.

Currently, Perseverance is studying both the geology on the floor of Jezero Crater and an area called Séítah (meaning “amidst the sand” in Diné, the native Navajo language), which has geologically interesting features like ridges, layered rocks, and sand dunes.

It wasn’t by accident that the rover was sent to Jezero Crater: Scientists believe this region of Mars once had a liquid lake, which means there’s hope it contains evidence of ancient microbial life.

[Related: Sorry, there’s probably no water under the South Pole of Mars]

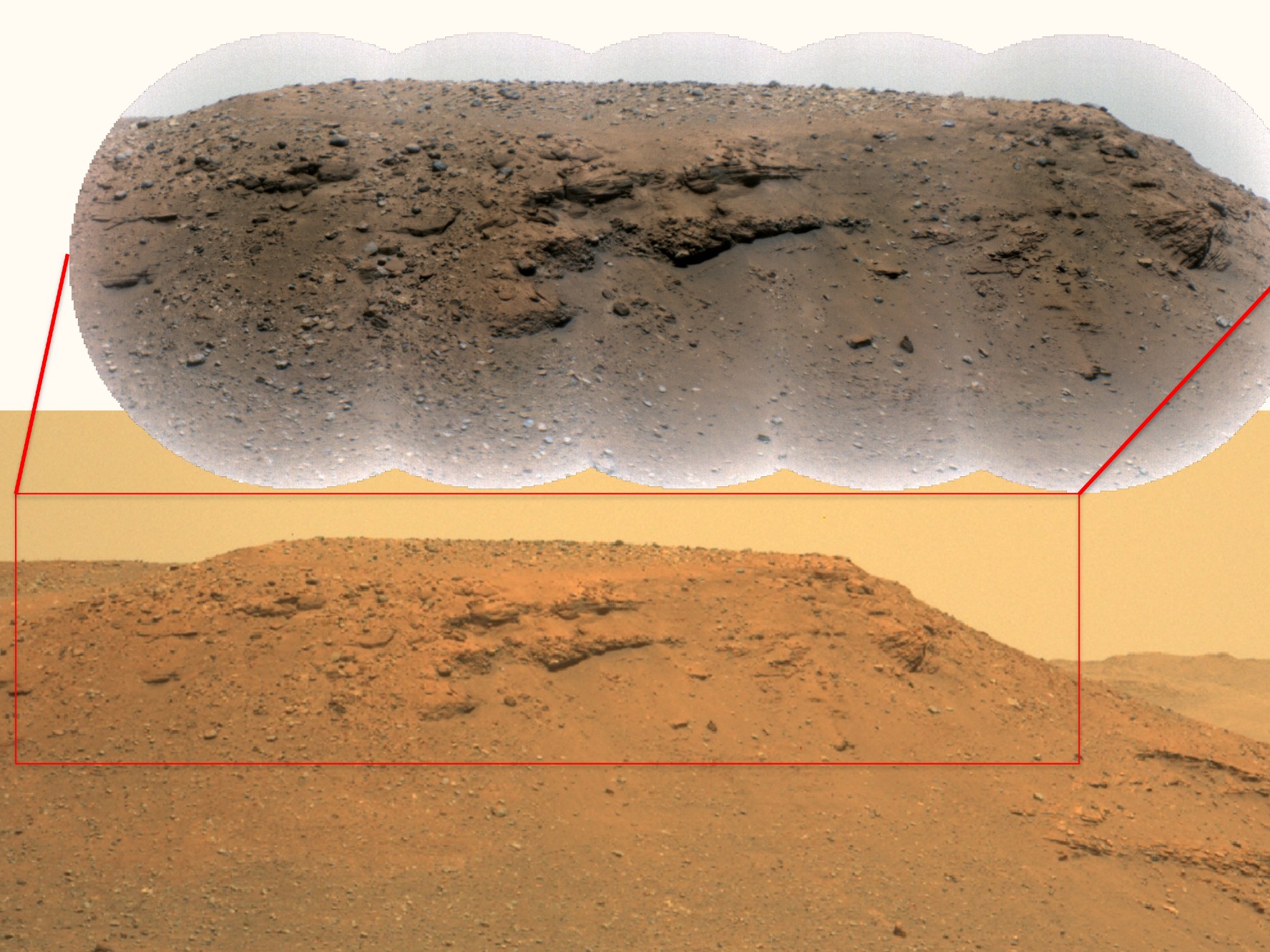

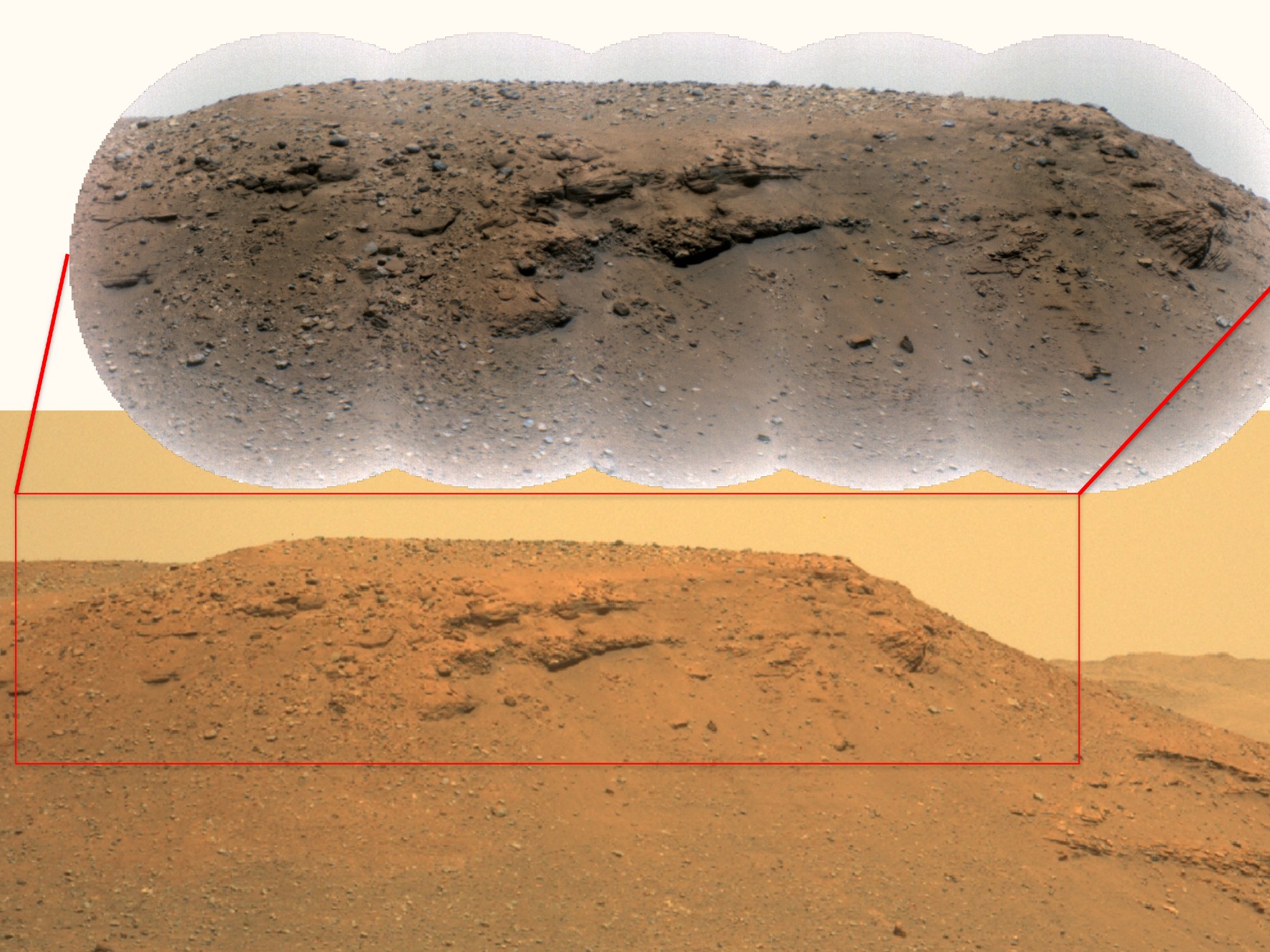

“We see clear evidence that there was indeed a lake [in Jezero Crater],” said Ken Farley, a project scientist for Perseverance, at a NASA press conference last month. The rover has spotted layered rocks which were probably built up as the composition of the water body changed, supporting the idea that the lake grew and shrank over time and could even have had flash floods. These rocks could hold evidence from multiple time periods trapped in the many layers of deposits, and have a better chance of showing signs of past life from any of those wet eras, compared to a rock sample that was formed all at once (like cooled lava, for example).

Later on, the rover will head toward an even more interesting site: the remains of a lake delta which lie just 2 to 3 kilometers away, Bell says. So far the rover has traveled just over two kilometers. After the primary mission, which lasts one Martian year (a little over two Earth years), NASA scientists have plans to explore further, possibly beyond the edge of the crater.

“We’ve spotted some really interesting rocks that aren’t too far away and that are scientifically interesting,” Bell says of Perseverance’s next sampling goals. He says the team is currently figuring out how to navigate the rover closer to figure out if, “in fact, these are the droids we’re looking for”—meaning rocks that are hard enough to extract a solid rock core sample from.

Perseverance has already taken pictures of at least one potential sampling spot with layered rock, possibly built up from successive layers of mud over millennia. A sample sliced from that Mars cake would give a cross section of millions of years of lake deposits, providing scientists with a window into how the lake changed over time—and whether life ever emerged there.