Turning off your lights at night may mean more than just saving energy. For migrating birds, bright buildings are just another of a long list of threats to their populations. Of the more than one thousand bird species that are protected under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, 92 are listed as endangered.

A new study in PNAS based on decades’ worth of data on birds collected by Chicago’s Field Museum scientists. The researchers found that turning off lights in buildings significantly decreased the deaths of migrating birds like warblers and thrushes. On nights when half the windows were darkened, there were 11 times fewer bird collisions during spring migration and six times fewer collisions during fall migration than if those windows stayed lit.

Estimates indicate that between 365 million and 988 million birds die annually from collisions with buildings in the United States. Threats to migratory birds, including weather conditions and light pollution, have caused North America to lose “nearly one-third of its birdlife in the last half-century with migratory species experiencing particularly acute declines,” the authors write.

“Our research provides the best evidence yet that migrating birds are attracted to building lights, often causing them to collide with windows and die,” Benjamin Van Doren, a postdoctoral associate at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and the paper’s first author said in a press release. “These insights were only possible thanks to over 40 years of work by David Willard at the Field Museum, who led collisions and light monitoring efforts.”

[Related: One of the most important laws protecting birds in the US just got gutted.]

In the late 1970s, Willard, the Field Museum’s collections manager emeritus, heard about birds hitting McCormick Place, a large convention center in Chicago. He found five dead birds that day. After 40 years, he has seen about 40,000 birds meet their demise after colliding with this one building alone.

In the 1990s, after two decades of recording and collecting dead birds Willard and his colleagues discovered the pattern of fewer deaths around specific times, specifically holidays when lights in the center would be turned off.

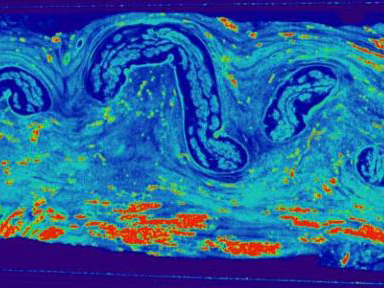

“It was quickly clear that there was a general correlation between the amount of light at McCormick Place and the number of collisions,” Benjamin Winger, an assistant professor in the University of Michigan Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and senior author said in the press release. “But to really understand the relationship between artificial light at night and collisions, a more sophisticated analysis that also involved data on migratory passage from radar and weather patterns was required.”

Willard and the other researchers developed a statistical model based on the number of windows that were illuminated in the McCormick Place, the weather conditions, the time of season, and the migratory passage of different bird species. It allowed them to isolate different factors and to pinpoint that though weather and the number of birds in the sky were a factor, lighting played the most role in the uptick of bird deaths.

There have been past efforts to stop light pollution that birds across the country. In 1995, Chicago implemented the Lights Out Chicago program that encouraged owners or managers of tall buildings to dim or turn off decorative lights to protect migratory birds. In New York City, volunteers and members of the local Audubon society monitor 9/11 memorial lights. If too many birds start to swarm, volunteers alert the museum and memorial staff to periodically shut off the bird-attracting bulbs.

Saving migratory birds can be as simple as having scheduled shut-offs until certain species fly off to their next destination—something the researchers hope to see applied soon.

“Our study contains a hopeful message: We can save birds simply by turning off lights during a handful of high-risk days each spring and fall,” Van Doren said. “By adapting our existing public migration forecasts to identify nights with high collision risk, we will be able to issue targeted lights-out advisories several days in advance.”