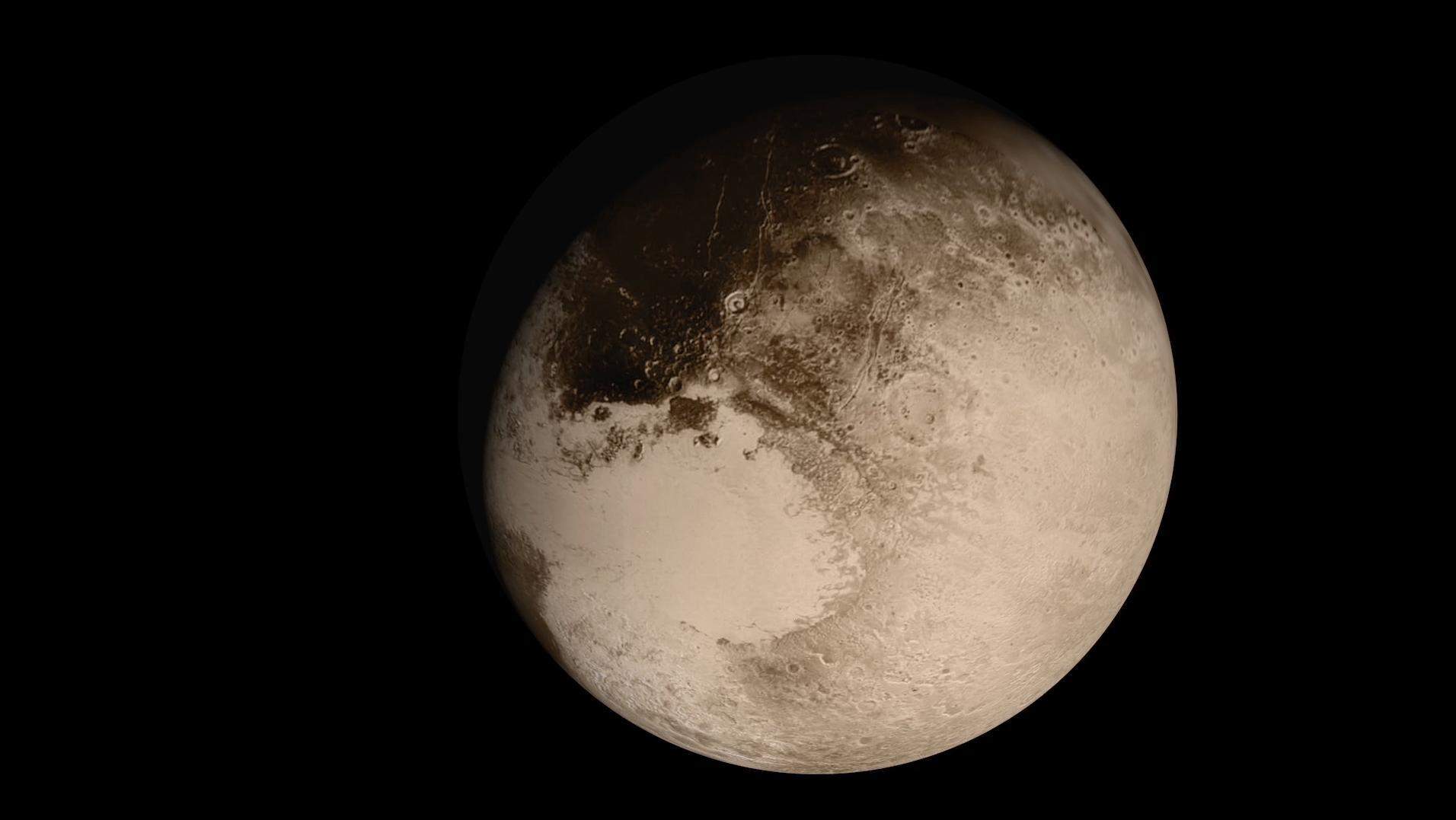

It was a lazy, hazy, crazy day on Pluto when a spacecraft from Earth flew by at a blistering speed of 31,000 miles per hour two years ago.

New Horizons took a bunch of snapshots, made some quick measurements of Pluto’s atmosphere, and sent them all back here, giving planetary scientists their first up-close look of the distant dwarf planet.

One of the more bizarre things they found was that the haze in Pluto’s atmosphere was much thicker than our previous peeks indicated. The icy hunk of rock also had an atmosphere much cooler than earlier estimates, topping out at -333.4 ºF (more than 50 degrees colder than expected, even for something about 40 times further from the Sun than Earth is).

Now, a study published in Nature links those two atmospheric observations. A computer model developed by University of California Santa Cruz planetary scientist Xi Zhang and colleagues shows the haze of tiny droplets in the upper atmosphere is likely scattering light from the Sun, preventing heat from reaching the planet below.

“It’s been a mystery since we first got the temperature data from New Horizons,” Zhang, said in a statement. “Pluto is the first planetary body we know of where the atmospheric energy budget is dominated by solid-phase haze particles instead of by gases.”

We see hazy skies on Earth too from time to time, whenever solid particles get suspended in the air—from water-based fogs, to ash and soot from fires, to the toxic droplets that make up a thick smog. But on Earth, the overall temperature of the planet is dominated by the distribution of gases in our atmosphere. On Pluto, the authors suggest, haze might be more influential.

This haze appears to be made up of large hydrocarbon droplets, created high in the atmosphere when ultraviolet light from the Sun strips electrons from particles of methane and nitrogen gas. The reaction helps form solid bits of hydrocarbon. But what gets created up there must still come down. Pulled back to the surface by gravity, the hydrocarbons start to bond together, eventually creating a thick haze. It doesn’t completely block sunlight, but rather absorbs and re-scatters it, theoretically warming up part of the atmosphere while keeping most of Pluto frigid below.

We know that particles can reflect light from the Sun here on Earth. We’ve seen it happen after volcanos erupt, putting sun-scattering aerosols into the atmosphere. Some people even propose mimicking this phenomenon to alleviate the effects of climate change. But our planet isn’t dominated by that process, or at least it hasn’t been for a few billion years.

If Pluto’s atmosphere is very different from ours and from that of other nearby planets, it could help scientists expand their understanding of exoplanet atmospheres. But right now, an accompanying paper [paywalled] points out, this is just a good guess based on data from New Horizons and a sophisticated computer model, not direct observations of the haze’s composition. There are other theories floating around to explain Pluto’s cool temperatures, including blaming the frigid air on gases in the atmosphere. Luckily, the authors will get a chance to test their notions when the James Webb Space Telescope launches in 2019. That observatory can detect infrared light, which the hazy Plutonian atmosphere would be positively glowing with as it scattered sunlight. The researchers just have to wait and see if the light from the telescope validates their bright idea.