In an effort so astronomically full of cooperation and enthusiasm it could have been scripted, last Sunday, some of the streets near Comodoro Rivadavia, Argentina went dark.

Streetlights blinked out, and a major highway closed for two hours to prevent the glare of headlights from obstructing the view of 24 portable telescopes all pointing at a distant, unnamed star. Semi-trailer trucks were driven to remote locations to help block the telescopes (and the astronomers crewing them) from the harsh, Patagonian winter wind.

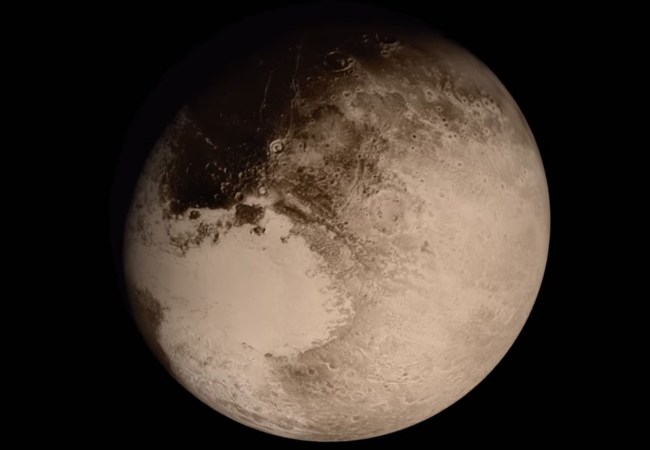

Then 60 researchers waited for the star to blink. They were watching for the few fractions of a second when a distant object in our solar system would zip in front of the star, giving us our closest and best look at the next target for NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft, which is still speeding through the outer solar system after its triumphant flyby of Pluto two years ago.

2014 MU69 is a cold classical object a billion miles further away than Pluto. It’s something that researchers think has been around since the very early days of the solar system. We don’t know much about it—not even its size or shape. But thanks to measurements gathered by the Hubble, we do know its trajectory.

The effort on Sunday was the last in a set of three observations that occurred in June and earlier in July in an attempt by astronomers to get a better look at the object before New Horizons goes flying by it on New Year’s Day, 2019.

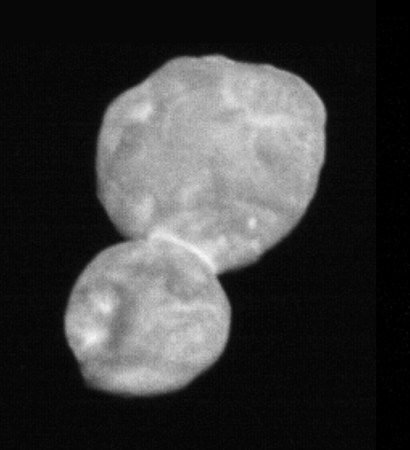

By watching as 2014 MU69 passes in front of a light source like a star (a process known as occultation) researchers can get more information about how big the object is, and if there is any debris around it (like rings or moons) that might pose a problem for New Horizons.

The first two attempts yielded some information, but didn’t quite capture 2014 MU69 crossing directly in front of a star. The last effort had more luck. New Horizons scientist Amanda Zangari was the first to notice that the telescope she was working on had captured the needed data. In the end, five of the 24 telescopes that were deployed managed to catch MU69 in action, which is great news for scientists.

“If you have one measurement of a shadow you can only really measure the minimum size of the object,” says Alex Parker, a NASA astronomer on the project who also was on the team that discovered 2014 MU69. “More than one, then you can really start to constrain the actual size of the object because you can start to tease out its shape. But with five you can do a really good job. “

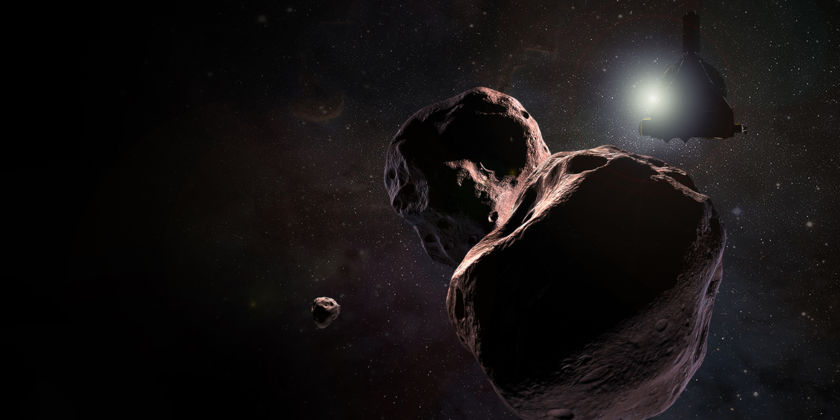

Parker says that while it will take a while to process, the new information can help the team figure out how to calibrate New Horizons’ instruments for the flyby. Knowing if the object is large and dark, small and bright, or some other combination can help the team decide whether to have a long or short exposure on New Horizons’ cameras, enhancing the chances that we’ll get images and data from the most distant object ever explored by human technology.

“This is really the first time we’re seeing the size of the object we’re sending New Horizons to,” Parker says. Parker wasn’t at the latest mission to Argentina, but participated in one of the earlier attempts this year. He was also part of the group scouting locations for where to set up the telescopes.

“We had to go up to farmers’ doors and say ‘Hi, we’re here from NASA, we’re wondering if we can set up telescopes in your back pasture?’” Parker says. “More often than not people were like ‘that sounds awesome, sure, we’ll help out!’”

In order to know which fields were suitable, astronomers had to develop completely new methods of combining data from the Hubble with an existing and remarkably detailed star catalogue. That enabled them to predict where the shadow of the object would fall on Earth at a particular time. The fact that it worked is incredibly exciting to everyone working on the New Horizons project, because it gives them more confidence in their measurements as they continue to ramp up planning for the 2019 flyby.

“This is kind of sight unseen. We’re flying to this object whose orbit around the sun takes hundreds of years, we only discovered it in 2014, it’s the faintest object that we’ve ever tracked for more than a year with any kind of telescope facility, and we’re trying to fly a spacecraft to it,” Parker says. “We’re doing this flyby at super high speed, so it all comes down to being extremely precise and accurate with our modeling and knowing where it is.”