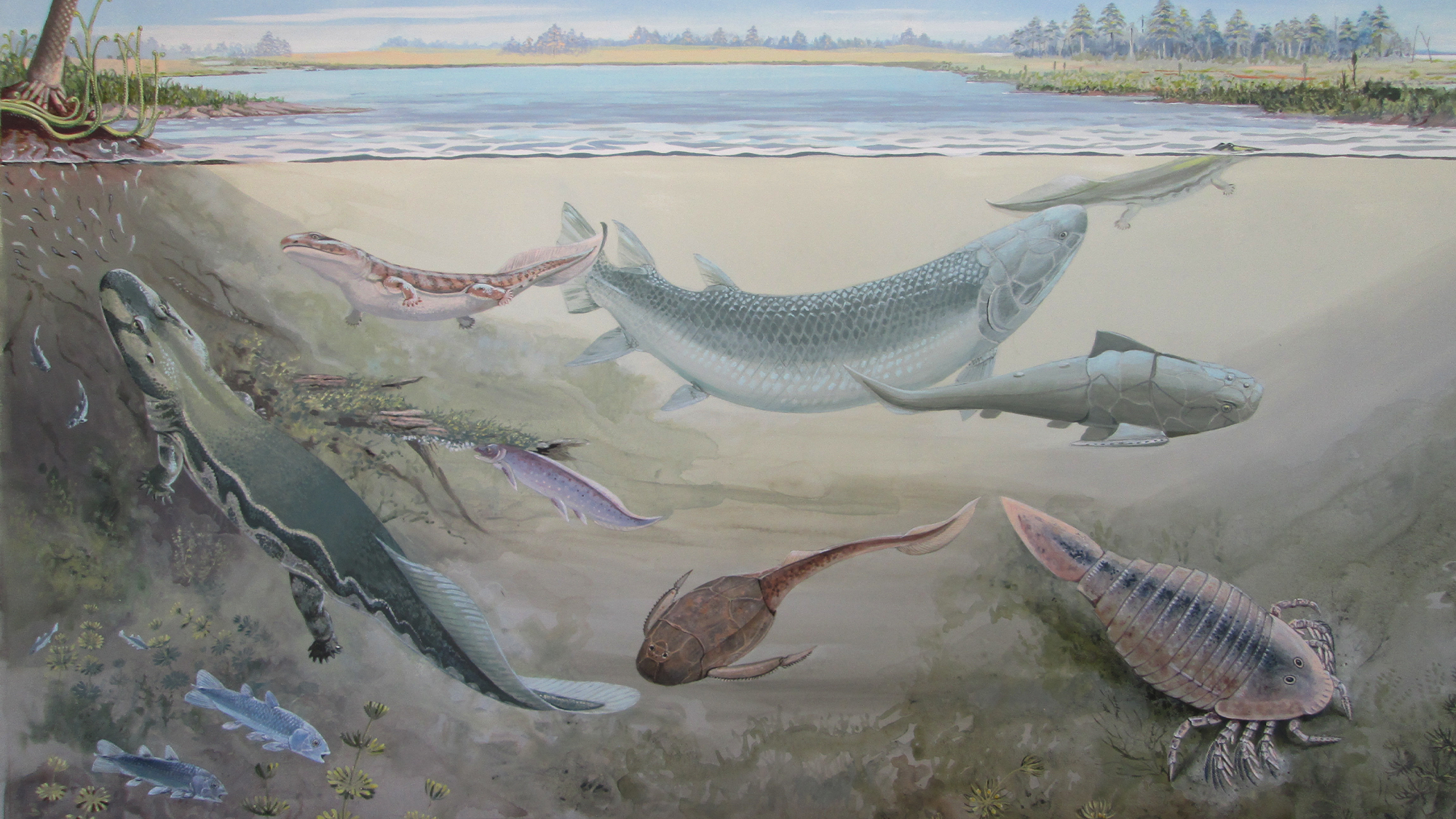

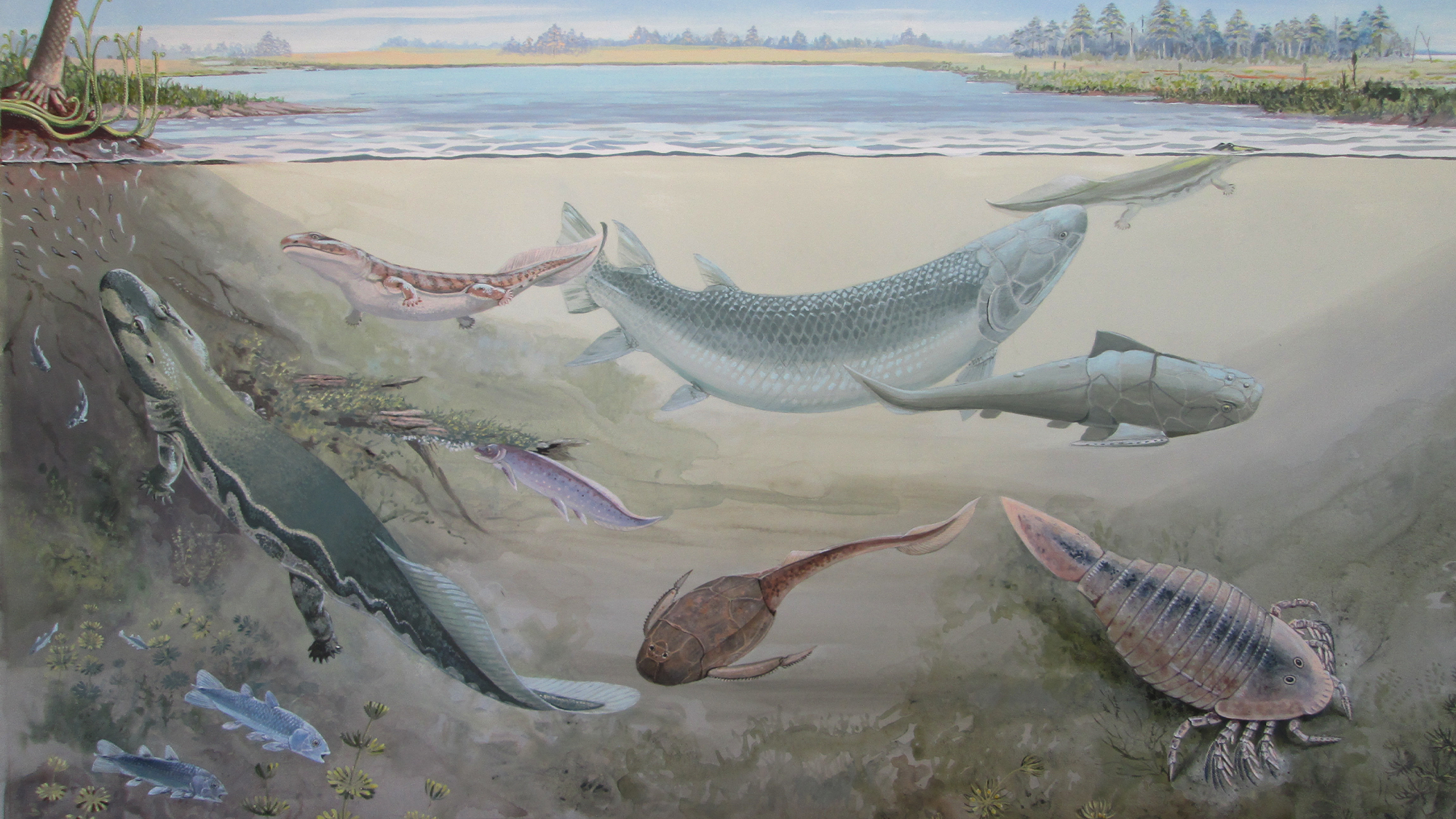

The waters of the 360-million-year-old subcontinent Gondwana were a dangerous place for a swim. A killer, bony fish the length of an adult California sea lion stalked freshwater rivers as a top predator. It was massive—as a new discovery reveals, this was the largest prehistoric bony fish ever discovered in southern Africa.

Its ferocity is reflected in its name, Hyneria udlezinye (H. udlezinye), which means the “one who consumes others,” in IsiXhosa, an Indigenous language spoken widely in southeastern South Africa where its bones were found.

[Related: One wormy Triassic fossil could fill a hole in the evolutionary story of amphibians.]

“Picture a fish looking a bit like a gigantic alligator. About 8 feet long, but with a more rounded head like the front end of a torpedo,” Per Ahlberg, a paleontologist and zoologist at Uppsala University in Sweden, tells PopSci. Ahlberg is the co-author of a study published February 22 in the journal PLOS One describing the carnivore. “The small eyes are located near the front of the head. In the mouth there were rows of small pointed teeth together with pairs of large fangs, up to a couple of inches tall.”

The specimen was found on the edge of Makhanda, South Africa, at the Waterloo Farm lagerstatte, a fossil site rich in specimens from the Late Devonian world, about 419.2 million and 358.9 million years ago. Co-author Rob Gess, a paleontologist from the Albany Museum and Rhodes University, South Africa has been collecting specimens from the site since 1985, where he has uncovered bones, teeth, and small invertebrates, as well as weeds and plants.

“This fossil site is globally significant for understanding biogeography of the Late Devonian world as it provides us with the only known window into a polar ecosystem during this pivotal time interval,” Gess tells PopSci.

But the remains of bigger things lurk there, too. H. udlezinye belongs to an extinct group of lobe-finned fish called the Tristichopterids. Late in the Devonian period, one branch of the Tristichopterid family developed into a cluster of giants. These huge Tristichopterids possibly arose in Gondwana, the ancient supercontinent, before migrating to Euramerica. The study authors determined that H. udlezinye is closely related to its North American cousins by comparing it with specimens of Hyneria lindae found in Pennsylvania’s Catskill Formation. The authors say that this supports the idea that all of these giants originated in Gondwana and adds a piece to their evolutionary puzzle.

[Related: Tiktaalik’s ancient cousin decided life was better in the water.]

All other fish in the Tristichopterid group were largely believed to live in the more tropical, or central, regions of the subcontinent, but these specimens were found south of where the paleoantarctic circle (our southern polar circle) was at this time. This suggests a more global distribution of the fish, from the equator down closer to the poles.

H. udlezinye was a ferocious predator that would have eaten most of the larger kinds of fish—including the relatives of modern coelacanths—and four-legged animals found near the site. Their body shape also suggests that they were likely “lie-in-wait predators,” who quietly hid and then quickly lunged to grab passing prey with fanged jaws.

As fearsome as it must have been, this apex predator was not completely invulnerable. The Tristichopterids, along with many other species of lobe-finned and armor-plated fish, “went extinct in the End Devonian Mass Extinction event 358.9 million years ago—the second of the big five global extinction events that radically altered the make-up of life on Earth,” explains Gess.

Learning more about the Denovian world can help scientists better understand not only the flora and fauna that went extinct during this mass extinction event, but also more about evolution and even ourselves as humans.

“This was a particularly interesting time in the history of the planet, when life had recently become established on land and was diversifying rapidly,” Ahlberg says. “Our own distant ancestors”—the earliest animals with four limbs, or tetrapods—“emerged out of the water during the Devonian.”