This week, a hospital in New Orleans reported two patients with a fungal disease caused by Candida auris, which can be deadly, hard to clean, and resistant to treatment. The cases were the first in Louisiana, and came just a month after Oregon reported its first outbreak.

Nirav Patel, chief medical officer of University Medical Center New Orleans, where the cases were reported, says that the fungus was spotted during general lab tests, which involved screening samples from patients for telltale proteins, including those produced by C. auris. “It’s a difficult-to-identify organism,” he says. “It’s hard for most labs to isolate it at a very specific level.” Because of that, it can be misidentified as another, less concerning fungus.

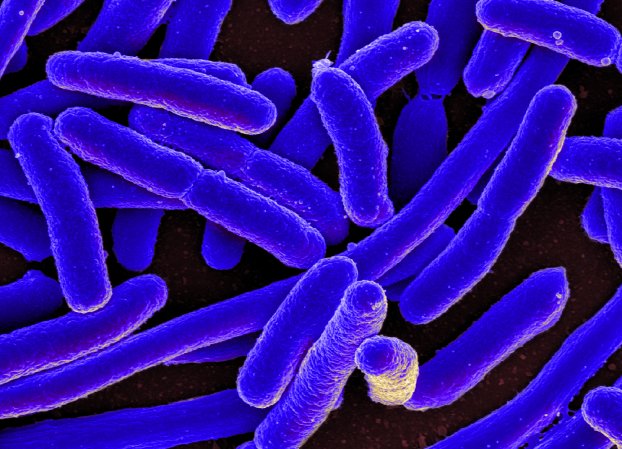

C. auris is a type of yeast that can grow on the skin of people with healthy immune systems, but it rarely gets inside. But in those who are weakened by an immune disorder or other illness, an infection can turn deadly. “Getting them [in the body] is hard, but once you get them, they’re really bad,” says Arturo Casadevall, an immunologist at Johns Hopkins University who studies fungal illness. “Fungal cells basically invade tissue and they grow as masses. People often get them in an IV, and then they can go anywhere.”

Between mid-2020 and mid-2021, more than 1,000 people were diagnosed with an infection, with the bulk of cases in Florida, Illinois, New York, and California. C. auris can be difficult to detect because the fungus manifests differently depending on where in the body it grows. One strain mostly causes ear infections, which can lead to pain, pus, and in the worst cases, an infection of the underlying bone. Infections in other parts of the body can result in flu-like symptoms. But in some cases, C. auris can be deadly: Around 30 percent of people with blood, heart, or brain infections die.

[Related: There’s a new fungal superbug, and it’s probably humanity’s fault]

The fungus is also exceptionally good at hanging out in hospitals and long-term care facilities, where vulnerable people are at high risk of developing severe disease. “This particular organism colonizes medical devices readily,” says Bhavarth Shukla, director of infection control at the University of Miami Health System. C. auris is known to invade the body during intubation with a ventilator. It also easily spreads via surfaces, and can survive some disinfectants commonly used to clean medical equipment and facilities. (Alcohol, bleach, and other sanitation products still work.)

“This is different than COVID, where you need masks,” says Patel. “It’s making sure we maintain strict isolation, good hand hygiene, [and] environmental cleaning.” UMC, he noted, was already using cleaning products that had been tested on C. auris.

Unlike the coronavirus, C. auris is not known to be an airborne pathogen, and transmission typically occurs through physical contact and spreads through the bloodstream. But C. auris cases have become a rising threat during the pandemic. In a paper last fall, Shukla and colleagues described a dozen patients in the COVID-19 ward during the summer of 2020 who were coinfected with C. auris. The team says resource shortages forced healthcare providers to reuse masks and gloves, which may have led to the spread of the fungus. But the combination of treatments and COVID infection could have also played a role. “There’s some evidence that the microbiome changes for COVID patients,” says Shukla, although why exactly that happens is unclear.

Critically ill patients were treated with steroids for COVID-19, as well as antibiotics to control bacterial infections. It’s possible that the combination of drugs cleared out C. auris’s microbial competitors, leaving patients vulnerable to fungal infection?. The outbreak cleared as COVID cases declined and as the hospital implemented control measures, so it’s hard to judge cause-and-effect, Shukla says. But Patel in New Orleans agrees that C. auris’s presence is a sign of a strapped medical system.

Disease-causing fungi are, in general, less understood than other pathogens. Humans are much more closely related to fungi than bacteria, or even plants, making it hard to develop safe treatments. Drugs that kill fungal cells are also more likely to kill human cells, causing some antifungal treatments to have debilitating side effects. There are only three basic types of antifungals available for treatment that each target unique features of fungal cells. According to the CDC, 85 percent of C. auris strains are resistant to a drug that hits the cell membranes and 33 percent are resistant to those that poke holes in fungal cells. Only one percent of strains are resistant to the third type of antifungal, which targets a cell wall sugar. Still, there have been a few cases of “pan-resistant” C. auris in the US.

Patel says that they have sent samples out for testing, but don’t yet know if the New Orleans strains are drug resistant.

C. auris was first identified in a Japanese patient’s ear canal in 2009, hence the name “auris.” Genetics of various C. auris strains suggests that the fungus had spread across the world before it became deadly. But until 2019, when it was discovered in wetlands on the remote Andaman Islands in the Indian Ocean, no one had even seen the species in the wild.

“This thing just showed up in hospitals,” says Casadevall. “Where the hell did it come from? It was not in any fungal collection going back hundreds of years.”

Casadevall’s theory is that its emergence is related to climate change. Humans and other warm-blooded species, he says, have a natural shield against fungal infections, which don’t like the heat. But increasingly frequent heat waves could act like a sieve, selecting for fungi that are more and more tolerant of warmth. C. auris survives in environments 100 degrees Fahrenheit or higher, suggesting that it may have crossed a temperature threshold that allowed it to enter human bodies.

Researchers are looking into other potential driving factors of C. auris infections: The increase in long-term care may have also created the right settings for severe disease to emerge. The growing use of antibiotics could have cleared out a niche for a previously obscure fungus.

“I think that Candida auris is a reflection of the significant burden of infections in the healthcare system, but also the use of antibiotics,” Patel says. “When we have these sorts of bugs come out, it’s a reflection of antibiotic selective pressure more than anything else.”

But the rapid emergence of a drug-resistant fungus like C. auris isn’t a good sign. Recent research found resistant staph bacteria growing wild in hedgehogs without any antibiotic exposure, implying that other drug-resistant diseases can pop up fully formed. “We don’t even have a handle on how diverse the fungal world is,” says Casadevall. “I think the fear is that the next one could be [a C. auris strain] that could be [more] resistant, or spread by air, or more pathogenic.”