About 650 light years away, a planet hotter than many stars is hurtling around its sun, leaving a glowing trail of gas in its wake like some sort of superheated comet.

In a paper published Monday in Nature, researchers announced the discovery of the gas giant orbiting an incredibly hot star, KELT-9, which is twice as large and twice as hot as our sun.

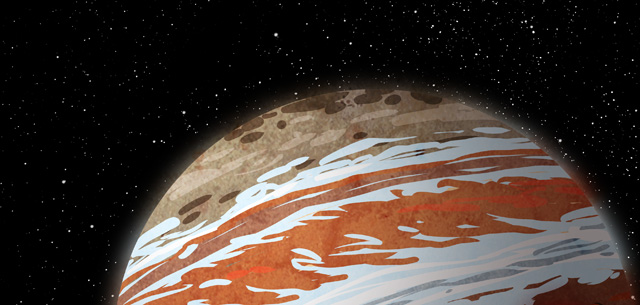

The Jupiter-like planet orbits KELT-9 over the star’s poles—as opposed to around the star’s equator—at a rapid clip. It transits once every 36 hours, passing between its host star and Earth’s observing telescopes. The planet, known as KELT-9b, is tidally locked, with one side constantly enduring the intense radiation of its sun and the other side plunged into perpetual night.

On the day side of the planet (which is almost three times the size of Jupiter, but only half the mass) temperatures reach 7,800 degrees Fahrenheit. That’s only about 2,000 degrees cooler than our own Sun, and it’s the same temperature of stars called brown dwarfs.

But despite its size—and the heat of its surface—the researcher say it’s definitely not star material.

“The inside of the center of the planet is nowhere near hot enough to fuse hydrogen and helium,” says study author Scott Gaudi.

Gaudi and his colleagues kept track of the planet with the help of observations from volunteer amateur astronomers, watching as the planet crossed in front of its star and disappeared behind it. One of the major telescopes used in this endeavor was the Kilodegree Extremely Little Telescope (KELT), which helps astronomers look for planets around very hot stars, like KELT-9. The researchers used those measurements and observations to start getting a clearer picture of what this strange planet is like.

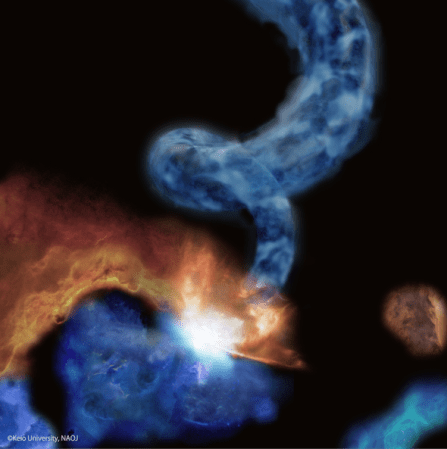

For one thing, the extreme radiation and heat from the star are probably pushing material out of the planet, forming a glowing trail of gas behind it. And molecules like water or methane couldn’t form in the intense heat of the day side of the planet.

Most other things about the planet remain unknown, but researchers do think that the planet’s strange orbit points to a violent past.

“This planet has a very long and tortured history,” Gaudi says. He explains that planetary scientists think that many planets form in protoplanetary discs—vast discs of gas and dust orbiting roughly around a host star’s equator. The planets forming in the disc tend to stay in that same plane, but might get knocked into a different orbit (like the strange perpendicular orbit of KELT-9B) if another object slammed into it like a billiard ball.

And things aren’t likely to get much better in the planet’s future. Eventually, the intense radiation from the sun might evaporate the planet entirely, or reduce it to a rocky barren world like Mercury, depending on the planet’s composition. If not, then it will get obliterated when KELT-9 blows up into a red giant later in its life cycle.

But that’s a very long way off in the future. The researchers still hope to get time on other observing platforms, like the forthcoming James Webb Space Telescope, to help them gather more data about what the atmosphere on the planet might be like in the present. They also hope to learn how well heat is transferred from the day side of the planet to its cooler night side. Strong winds might help redistribute the heat around the planet, but more observations are needed.

There’s still plenty of time to make observations, but this particular planet won’t be visible from Earth forever.

“We were pretty lucky to catch the planet while its orbit transits the face of the star,” co-author Karen Collins said in a statement. “Because of its extremely short period, near-polar orbit and the fact that its host star is oblate, rather than spherical, we calculate that orbital precession will carry the planet out of view in about 150 years, and it won’t reappear for roughly three and a half millennia.”