When life hands you lemons, you make lemonade. And when life hands you pearlfish that want to burrow up your anus, you grow teeth on your anus.

The animal kingdom is a pretty weird place, and science writer Matt Simon has made it his job to enlighten you about some of the craziest solutions evolution has come up with to solve life’s challenges. Simon writes the Absurd Creature Of The Week column at Wired, and he’s just finished writing a book compiling all of the grossest, funniest, and most fascinating critters out there.

In this excerpt from The Wasp that Brainwashed the Caterpillar, which goes on sale October 25, we meet the pearlfish. These slender fish dwell near the barren seafloor, where there aren’t a lot of places to hide from bigger fish that want to eat you. The pearlfish’s solution: swim up a sea cucumber’s anus and eat its gonads.

They say home is where the heart is, but for the pearlfish, home is more like where the gonad is. Because to find shelter it wiggles up a sea cucumber’s anus. And lives there. And eats its gonads.

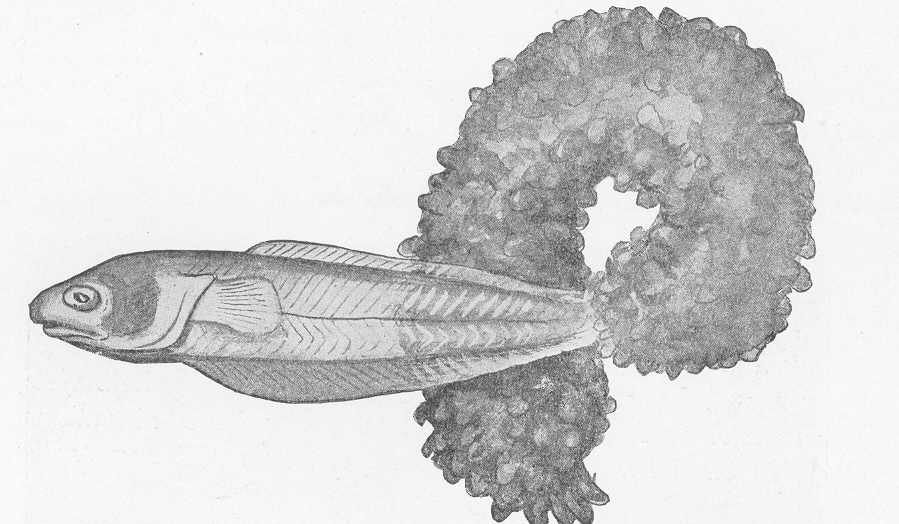

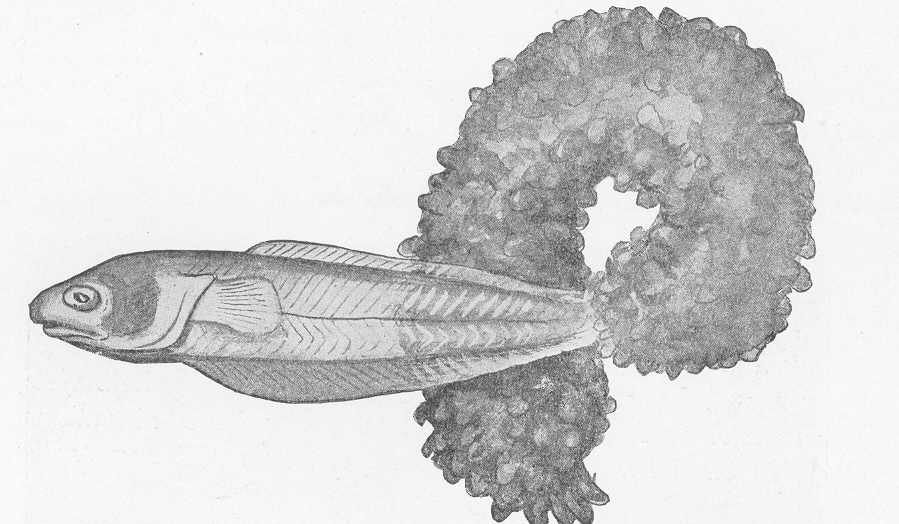

It all begins innocently enough. The skinny, eel-like fish approaches the sea cucumber and gives it a sniff, moving up and down the length of its soon-to-be victim with its body pointed almost vertically. It’s looking for the sea cucumber’s breath, because, well, sea cucumbers breathe through their derrières. If the sea cucumber detects the pearlfish, it’ll hold its breath, sealing its butt like a human holding in a fart. But the sad sack is only delaying the inevitable. At some point it has to breathe, and that’s when the pearlfish strikes.

Once the pearlfish sees its window of opportunity, it has to make one of the toughest decisions in the animal kingdom: whether to enter the sea cucumber’s bum tail first or head first. This, of course, all depends on the size of the orifice (called a cloaca, since it’s used for not just waste removal but also reproduction and breathing). If the opening is big enough to enter head first, the pearlfish goes at it full tilt, jamming its face in and rapidly flicking its tail to fire itself into the sea cucumber. If the opening is too small, the fish first inserts its thin tail, then backs in slowly.

Once the fish is in there it wiggles into what’s known as the respiratory tree, which branches out as tubes on either side of the sea cucumber’s intestines. The sea cucumber breathes by pumping water in and out of its cloaca and into the tree. So not only is the pearlfish enjoying shelter while it’s in there, it’s getting a constantly replenished source of water, and therefore oxygen.

Some species of pearlfish are content sitting there biding their time, safe from predators circling above. Others . . . they get a bit hungry. They’ll start feeding on various parts of the sea cucumber, including the gonads, which isn’t as bad as it sounds. Once the gonads are gone it can grow new ones. The same goes for its other organs: The critter is a remarkable regenerator.

While the sea cucumber can regrow the bits one pearlfish has eaten, another is bound to show up and hack away at its insides once again. In fact, a biologist once found fifteen pearlfish in one poor bastard of a sea cucumber.

And if you thought the fish were ignoring each other’s advances in there, you’ve got another thing coming. Pearlfish also get busy in the respiratory trees, the ultimate indignity after the sea cucumber has itself been sterilized. It takes a tremendous amount of energy and resources to reproduce. If a parasite can figure out how to sterilize its victim, that means more energy is available to support its own shenanigans. Whether sterilization is the pearlfish’s strategy or the gonad happens to be tasty isn’t yet clear. Could be both, really. You’d have to ask a pearlfish.

And pearlfish don’t limit themselves to taking up residence in sea cucumbers. Some species instead invade sea stars, and still others go after bivalves like oysters. Those strategies would appear to be better options, considering the sea cucumber itself is vulnerable, on account of being essentially a tube of meat wandering along the seafloor. But while it may look appetizing, in reality, it’s not, for the sea cucumber has a secret weapon: It disembowels itself to scare away predators.

Admittedly that doesn’t sound like an effective defense at face value, but hear me out. When a sea cucumber feels threatened, the connective tissues that hold its organs in place soften in an instant. Depending on the species, the body wall around either the mouth or the heinie also softens. With everything loosey-goosey, the sea cucumber contracts its muscles, firing its guts through the weakened body wall at one end or the other. The explosion is a kind of surprise that maybe, just maybe, is weird and smelly and goopy enough to scare away predators. And as traumatic as it all sounds, sea cucumbers can regenerate the lost organs in a few weeks.

Interestingly, the pearlfish doesn’t seem to trigger these defenses, and as yet no one is quite sure why. Maybe it’s more energetically cost-effective for the sea cucumber to deal with regrowing gonads than the intestines and all the other ejected bits. So what the pearlfish ends up with is a living, breathing mobile home, which staves off attack by dropping its guts out, like a James Bond car deploying caltrops to slow pursuers. Except the sea cucumber isn’t going to get the girl. You know, on account of missing its gonads.

Adapted from The Wasp That Brainwashed The Caterpillar by Matt Simon, on sale October 25, 2016. Reprinted by permission from Penguin Books, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2016 by Matthew Simon.