Lurking in the waters off the coasts of East Africa and Indonesia is the coelacanth—an ancient species of fish that can reach up to 6.5 feet in length. They reside in the ocean’s “twilight zone,” the dimly lit depths 500 to 800 feet below the surface. Little is known about these slow-moving giants. In fact, scientists previously thought they went extinct about 65 million years ago along with the dinosaurs. It wasn’t until the first live specimen was caught in 1938 that scientists realized the marine mammoths were swimming in the deep today.

Scientists have observed very few coelacanths partially due to their mysterious behavior—they spend most of the day clustered together in volcanic caves. The creatures are classified as critically endangered, which means fishing them is prohibited, so very few ever make it up to the surface. However, a study published this month in Current Biology has begun to unravel some of these scaly critters’ secrets.

The latest study, which was unfunded, found coelacanths live five times longer than once predicted. Prior to this discovery, marine ecologists believed the behemoths lived to the age of 20, which would have classified them as one of the fastest-growing aquatic species. Now, ecologists believe they could reach the ripe old age of 100, a relatively rare feat.

To scientists who know the bizarre creatures, a long lifespan actually isn’t a huge surprise. Characteristics like a slow metabolism, low oxygen extraction capacity, producing small batches of eggs, and ovoviviparity, or when a mother carries eggs within their body until they are ready to hatch all hint at a slow-growing, long-lasting life.

[Related: Animal Crossing’s most elusive fish has a bizarre real-life backstory.]

“That extremely fast growth rate once believed was extremely strange compared to other characteristics [of coelacanths],” Bruno Ernande, a marine ecologist at the French Marine Institute and co-author of the study says. “It was not fitting the picture. So this is why we decided to reinvestigate the age range of coelacanths.”

Uncovering secret growth rings

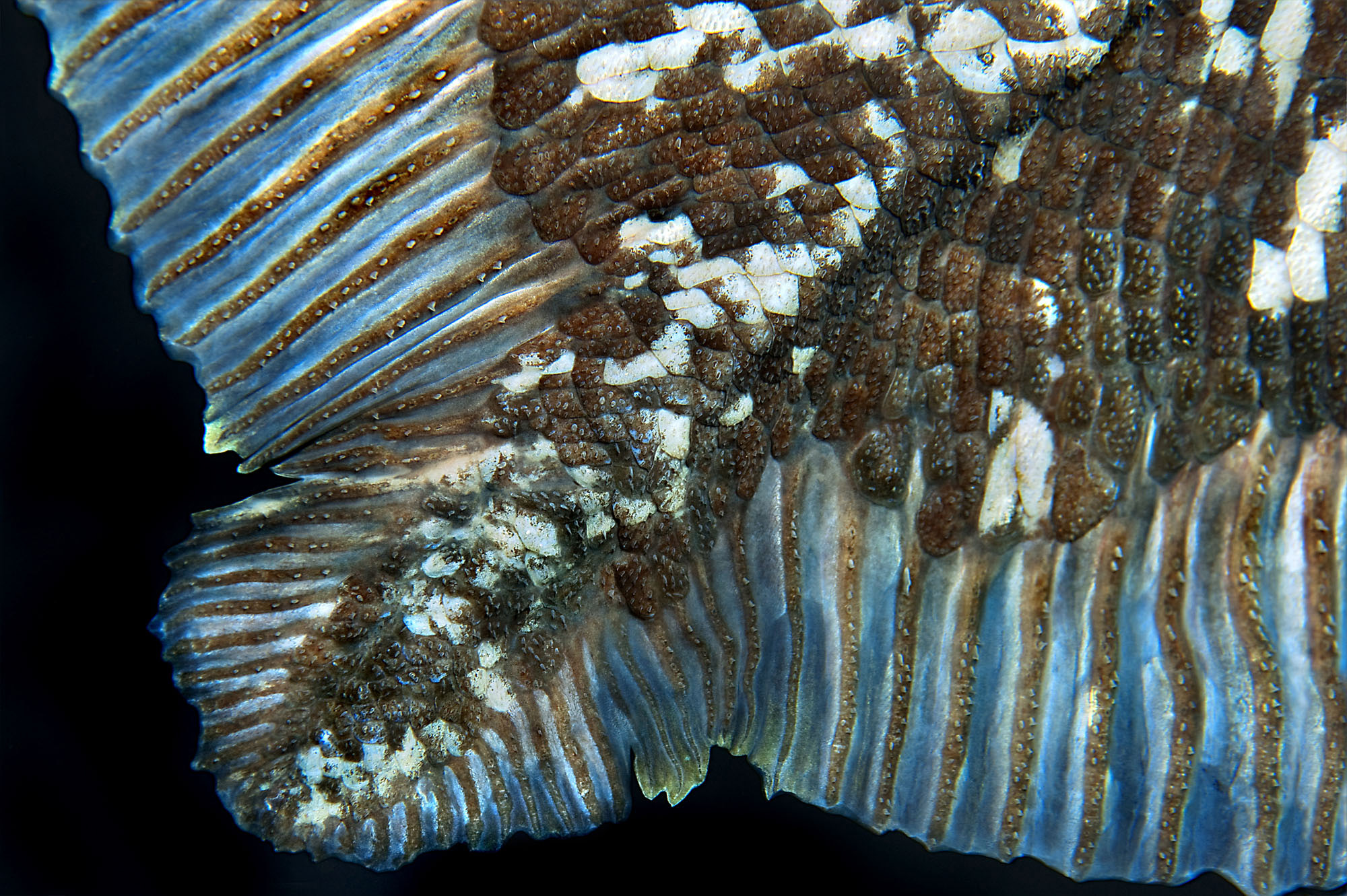

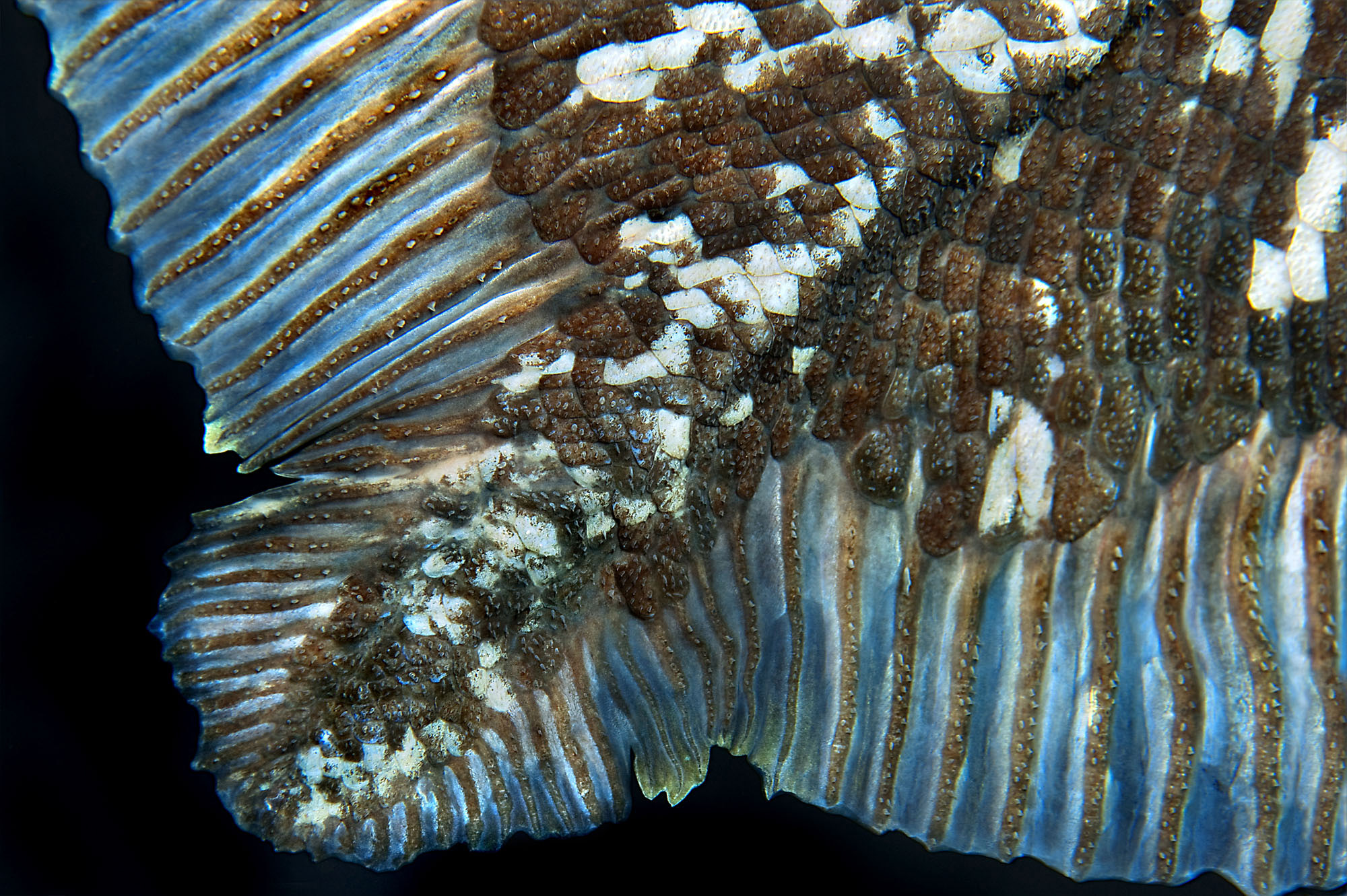

To determine the age of a fish, scientists count growth rings on their scales, much like tallying the rings of a tree trunk. Each ring corresponds to one year of life.

Past studies observed these growth rings with reflected light, like that found in a flashlight. However, Ernande and his colleagues utilized a more modern technology called polarized light which increases the contrast between the rings.

In total, the researchers examined 27 preserved specimens across varying ages and sex. The youngest were embryos and the oldest was 84-years-old.

“What we found when we used this different technique is that there were nearly imperceptible rings that originally went unnoticed,” Ernande says. For each bigger, thicker ring, he and his team found five faint ones. “So this is basically how we came to the conclusion that the age of coelacanths was underestimated by a factor of five.”

Thus, coelacanths may be able to live to the ripe old age of 100, and they don’t reach sexual maturity until their forties to sixties. And the animals don’t just live long lives—the aquatic giants have a gestation period of 5 years, which is possibly the longest of any marine fish and a decent chunk longer than most mammals.

[Related: ‘Living Fossil’ Fish Has Lungs.]

Ernande says his team is uncertain why every coelacanth specimens deposit bold bands every fifth year. They know it’s not due to environmental factors since the ribbons weren’t uniform across species, but it may have something to do with the five-year cycles of reproduction. However, this is entirely speculative, he says.

Why age isn’t just a number

Fishing, channel dredging, submarine blasting, and deep-water port construction, all threaten coelacanths, classifying the creatures as endangered and threatening their 360-million-year run on the planet.

Plus, species with a slow reproductive rate, such as coelacanths and the great ape, are particularly vulnerable to environmental or man-made changes. While some fish can carry over a million eggs per gestation, Ernande says, coelacanths only carry around 20 on top of being slow to mature and gestate.

“Any accidental or human-caused death takes a very long-time to replace,” Ernande says.

Understanding the true life span of these living fossils is essential for assessing the demography of the species, which, in turn, can inform conservation policy.

“There’s a lot more to be discovered about this species,” Ernande says.