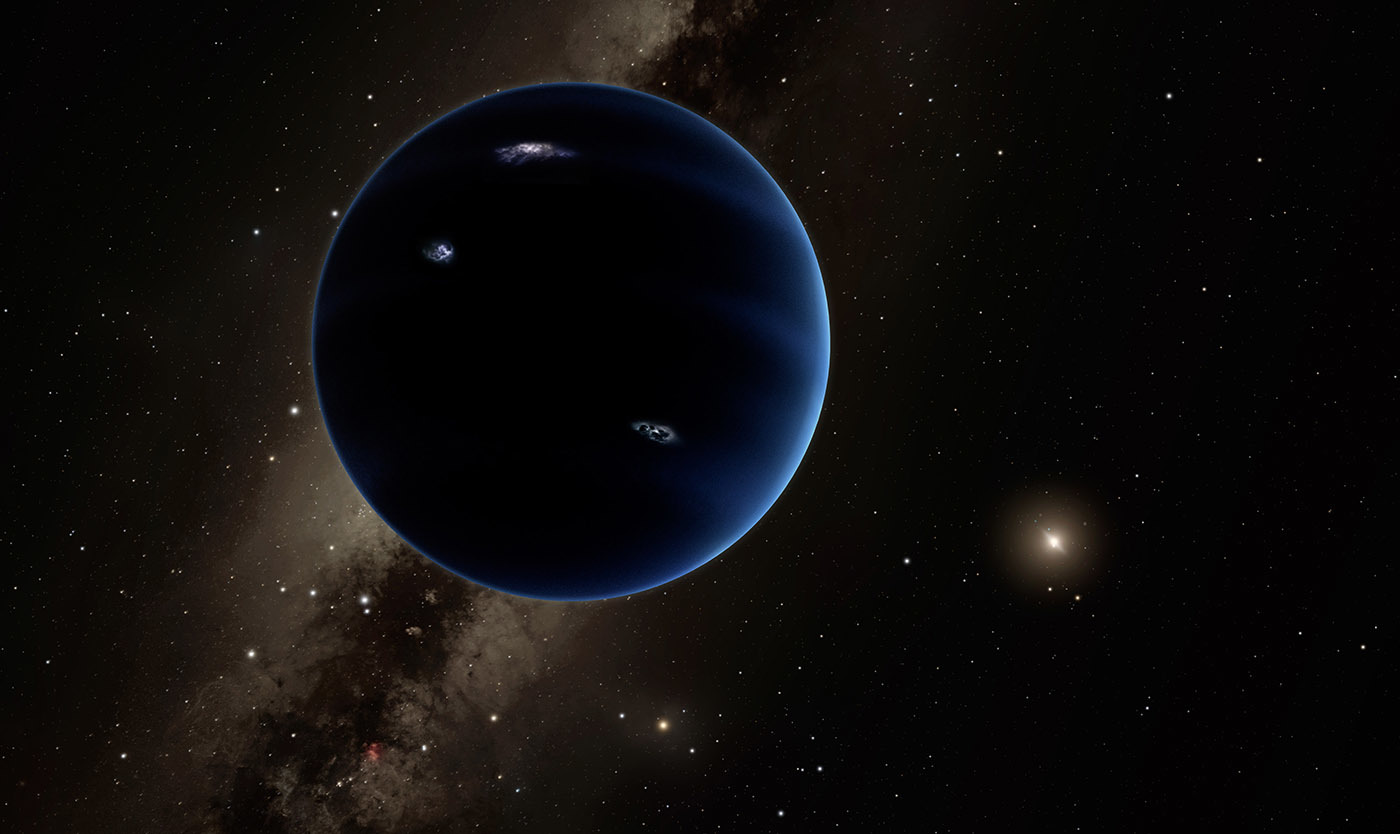

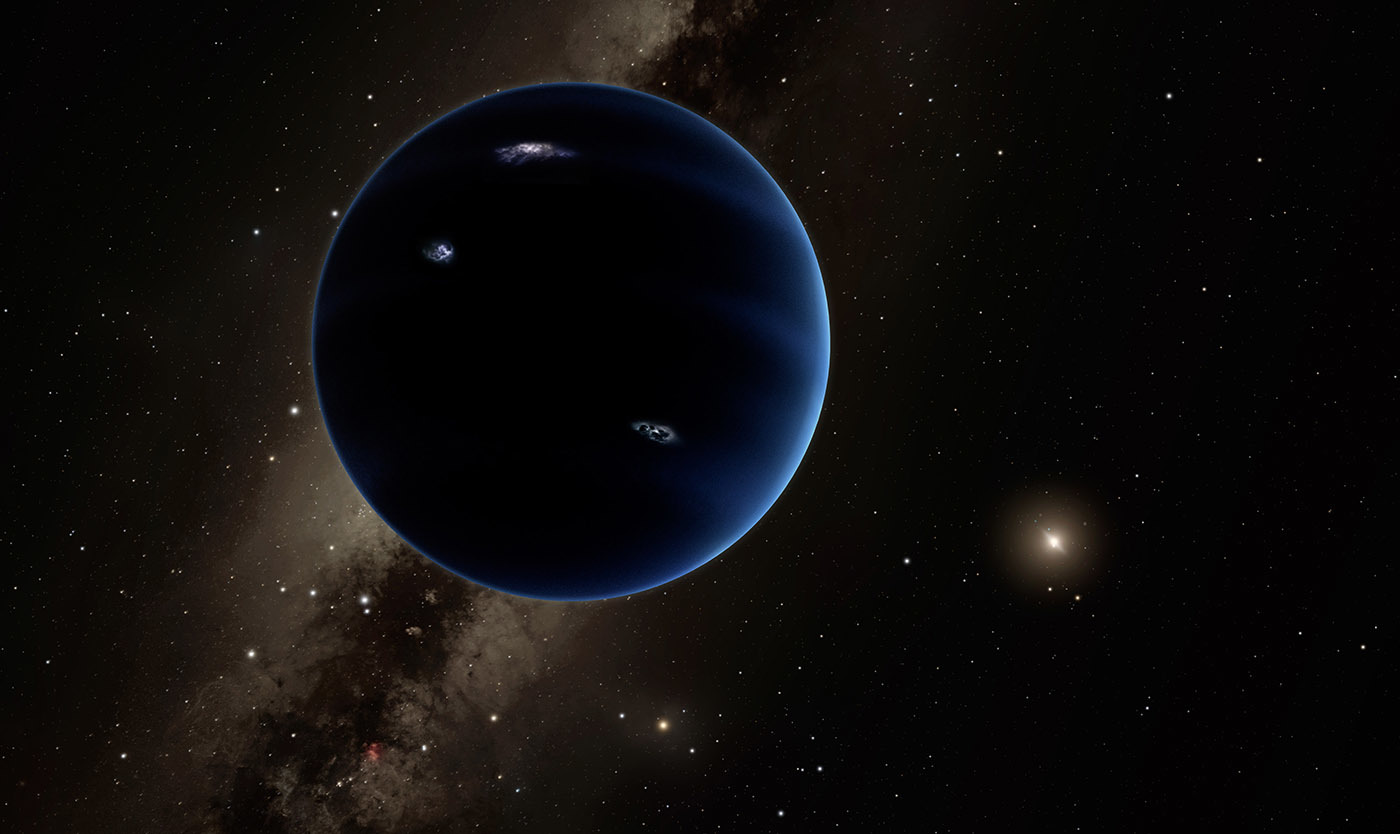

After centuries of watching the skies, the map of our local solar system has grown quite detailed. We live on one of the rocky inner planets. Next there’s a belt of asteroids, two gas giants, two ice giants, and then a second belt of many smaller icy bodies. In the impenetrable outer solar system, however, lies an unseen dragon, researchers have come to suspect.

Scanning the darkness, astronomers have managed to catch a few glimmers of what might fill the nether regions far beyond Neptune. And what they see doesn’t make sense. Where researchers predicted chaos—strewn flotsam leftover from the solar system’s tumultuous formation—they see unexpected order. Orbits of distant objects cluster together. Their points of closest approach stop short of a certain line for no apparent reason. In a handful of such patterns, many scientists see the work of some invisible entity.

“There has to be a lot more mass out there,” says Ann-Marie Madigan, an astrophysicist at the University of Colorado Boulder.

The leading theory is that a giant planet perhaps ten times heavier than Earth—Planet Nine— pushed its smaller neighbors around. A painstaking search for the dim bully has been underway for a few years, and as it stretches on alternative ideas are bubbling up. Madigan and collaborators, for instance, have found that a vast disk of smaller bodies could have identical effects, Scientific American reported last week. Other researchers have gone to the other end of the size spectrum, suggesting that the mystery object could be a softball-sized black hole. If either team is right, and there is no large object to find, current telescope hunts could continue to come up short. In that case, astronomers would have to get more patient, and potentially more creative.

One challenge to the Planet Nine theory is that while it explains the odd orbits of objects astronomers see today, theorists aren’t sure how such a huge planet could exist in the outer solar system. The sun’s gravity weakens along with its light, so a large planet that formed out there should have gotten snatched away by a passing star. Or if it started out close to the sun and then drifted outward, what stopped it? “If it’s a planet, it’s a weird place for a planet to be,” says James Unwin, a physicist at the University of Illinois Chicago.

But Madigan’s simulations have convinced her that she can get the weird, clustered orbits without the headache of Planet Nine. As the solar system formed, she says, Jupiter and Saturn should have punted lots of planetary rubble into long, oval orbits that collectively form an undetected washer-shaped disk beyond the realm of Pluto. Other researchers have assumed the tiny masses of any objects out there should amount to rounding errors math- and modeling-wise, but Madigan has discovered that they might add up after all.

When she runs digital models of the solar system, she finds that at one point in the distant past, the disk could have morphed into a short-lived cone before relaxing back down into a “puffier” disk. And when the dust settles in such systems, they display the same aberrations that inspired the Planet Nine hypothesis, according to two not-yet-peer reviewed publications posted this spring. “You can explain everything that’s been anomalous in the outer solar system,” Madigan says. “And that’s not something I say lightly.”

Still, she points out that her story requires its own leap of faith. For the disk to completely supplant Planet Nine, it needs 20 Earth masses of material, the absolute maximum amount of leftover debris predicted to exist. “We’re really just at the edge of what is reasonable,” she says.

Another team has proposed a smaller disk that operates through a different mechanism. This object could shoulder outer solar system sculpting responsibilities with Planet Nine, says co-author Antranik Sefilian, a doctoral candidate at Cambridge University, letting the theoretical size of both structures shrink.

Whether the culprit is a perfectly placed planet, an especially massive disk, or some combination of the two, astrophysicists are leaning toward the conclusion that something improbable has taken place in the outer solar system. And some are leaning farther than others.

Last fall, Unwin co-authored a publication speculating that the mystery mass could be a petite black hole left over from the formation of the universe. No such “primordial” black hole has ever been detected, but one survey has found circumstantial evidence that either rogue planets or black holes of Planet Nine-like mass might roam the Milky Way. If our sun could capture the former, Unwin reasons, why the latter? “This is a crazy idea,” he says, “but it’s not an unreasonable one.”

The tough task of deciding amongst the not-unreasonable ideas will likely fall to astronomers. Mike Brown, an influential champion of the Planet Nine theory, is leading a search for the elusive body that could end the debate at any time. Just last week while combing through astronomical data he spotted a point that looked promising, he recently recounted on Twitter, although it turned out to be a mock object he had injected to make sure his search process is working.

If Brown sees nothing, the next-generation Vera C. Rubin Observatory, which is anticipated to take its first images this year, will likely deliver a decisive ruling within five years. Because it will spot far fainter objects than current telescopes can, Madigan expects it to either pinpoint Planet Nine or to start mapping out the objects in her disk’s inner edge. Or, it could spot enough new objects that today’s observed patterns melt back into disorder and there ends up being no mystery to explain.

In the unlikely event that all current telescope surveys fail, and the anomalies endure years of the Vera C. Rubin Observatory’s operations, Unwin’s primordial black hole theory might start to look even more reasonable. Edward Witten, a theoretical physicist and string theory pioneer, imagined such a future last week when he published a pre-print describing extreme measures for locating the absolutely invisible: send out a search party.

Inspired by Breakthrough Starshot, an ambitious project that aims to someday send nanoprobes to the nearest star, Witten did the math on spraying a fleet of simple probes out in many directions, in the hopes that one might quiver as it flew past the black hole. Equipped with light sails, the probes would fly at perhaps one percent of the speed of light (pushed by a powerful Earth-based laser beam), bringing the journey to the realm of the theoretical black hole down to about a decade. Such probes could, if sensitive enough, complete a definitive map of mass in the outer solar system, be it in planets, disks, black holes, or all of the above.

A response published this week pointed out that once the probes leave the lee of the solar wind, jostling from charged particles might mask the tug of any black hole. Even those used to thinking big, however, acknowledge that the scheme will have to overcome a few more pressing hurdles first. Developing the launch infrastructure is expected to cost at least half a billion dollars, and the necessary laser and materials technologies don’t exist today.

“This is a super fun idea,” Unwin says. “However, it comes at a premium price tag.”