A tumultuous, meteor-heavy phase of Mars’s early life may have lasted longer than previously thought, according to the authors of a new study. Previous research had suggested that the rate of giant impacts into the planet had slowed 4.48 billion years ago, leading to a potentially habitable Mars 4.2 billion years ago. But if the new findings pan out, it could mean Mars stayed inhospitable for at least 30 million years longer.

The study identified grains of the mineral zircon in a Martian meteorite that appeared to be “shocked” by high pressures, indicating large impacts on the Martian surface.

These meteorite impacts hit rocks with unimaginable pressure, “essentially squeezing them like an accordion,” says Aaron J. Cavosie, a geologist at the Space Science and Technology Centre at Curtin University in Australia and an author of the study published Wednesday in the journal Science Advances. “This process can cause crystals to bend and break, and even rearrange atoms, resulting in microscopic damage that remains over time,” he says.

Typically, Cavosie’s group uses electron microscopy to identify shock damage in zircon from Earth and the moon. “Shocked zircons are found at the largest impacts on Earth,” he says, such as the Chicxulub crater from the dinosaur-killing asteroid impact in Mexico.

However, this time they applied this technique to zircon in a Martian meteorite called Northwest Africa 7034, or Black Beauty. The meteorite is a kind of “rubble pile” made from Martian soil, called regolith, which consists of fragments of material from across the planet, Cavosie says. The team studied 66 microscopic zircon grains on the fist-sized rock.

Zircon is “about the most resistant mineral in existence, maybe just the side of diamond,” says Allan Treiman, planetary geologist at the Lunar and Planetary Institute of the Universities Space Research Association who studies Martian meteorites and was not involved with the study.

Because it “sticks around pretty much forever,” the mineral is what scientists use to study the very early Earth, he says.

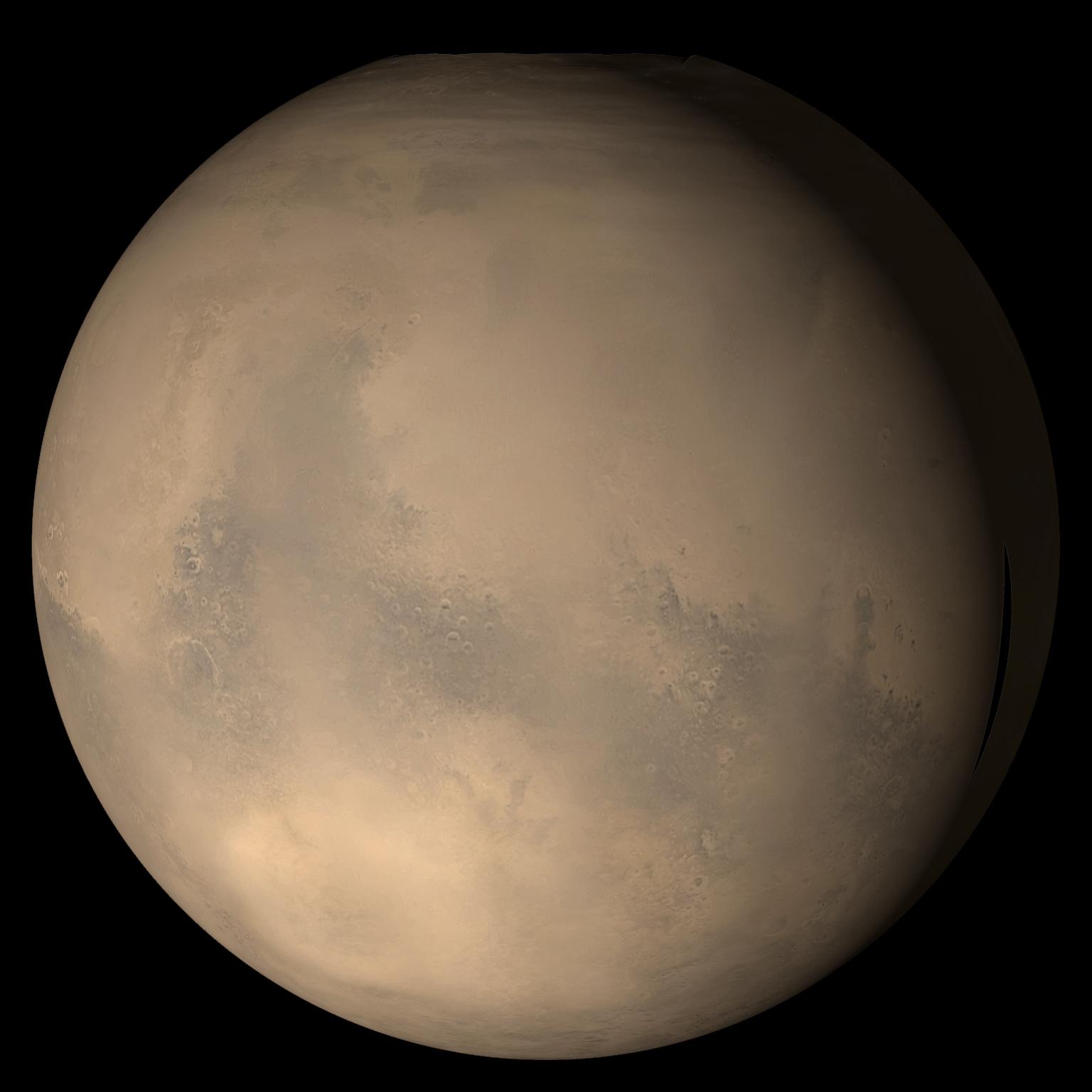

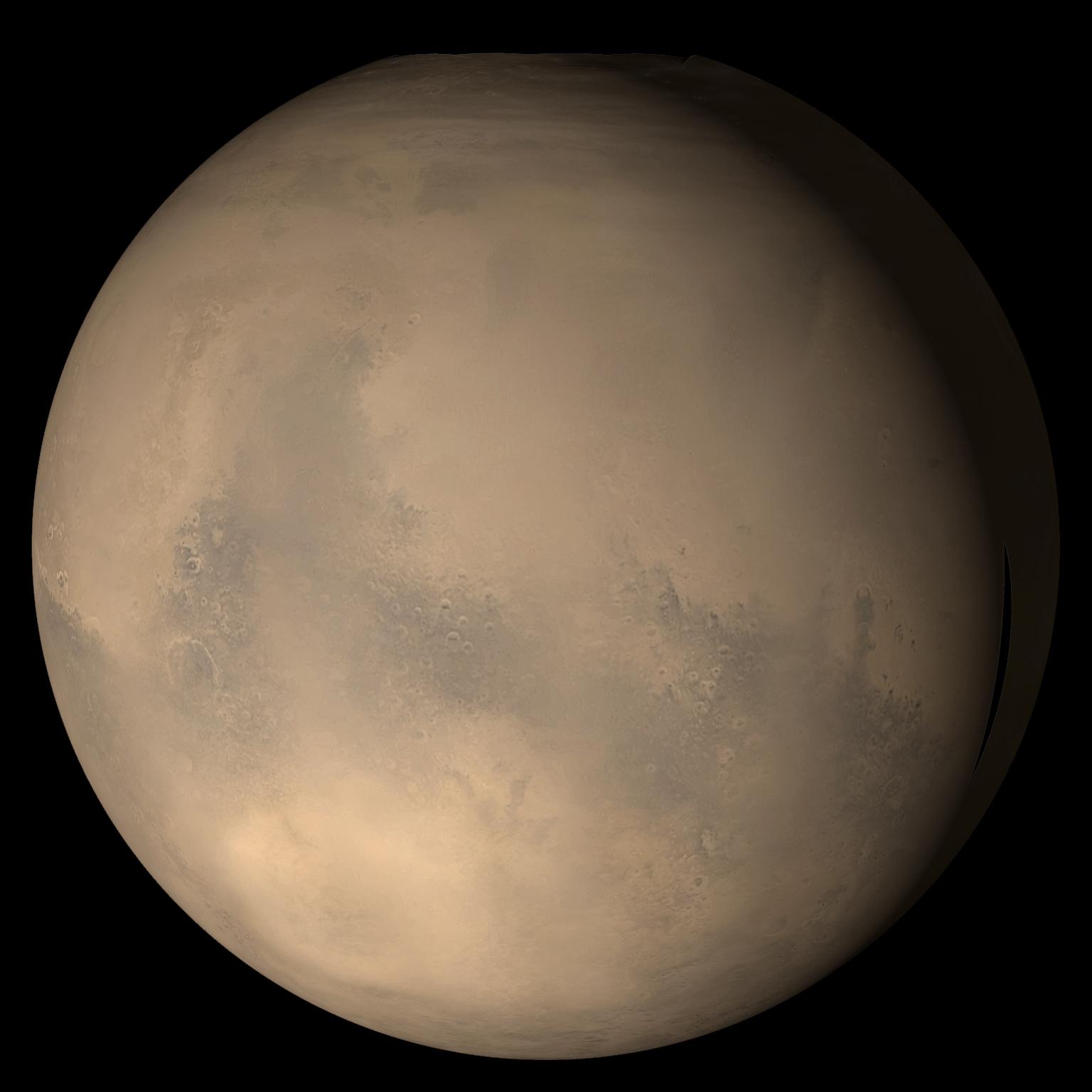

[Related: Mysterious bright spots fuel debate over whether Mars holds liquid water]

Most of the previous studies of zircon in Black Beauty focused on radioactively dating the formation of the crystals. This is only the second work to use a certain kind of electron microscopy to focus on signs of shock, Cavosie says, following a 2019 study by a different group of researchers. According to those radioactive measures, the zircon in Black Beauty crystallized about 4.45 billion years ago, “meaning it is among the oldest known zircons from Mars,” he says.

The group interprets the shock to mean that Mars was still being bombarded with large numbers of space rocks at this time, making it an unlikely time for life to evolve.

Treiman says the article was interesting and a sort of rebuttal to the 2019 study, which used similar evidence to arrive at very different conclusions. The 2019 study examined 121 similar zircon grains and found that only a handful showed signs of shock. Because the shocked grains were in such a stark minority, the authors took this as evidence that planet-wide meteor bombardment had already stopped by the time the rock formed 4.45 billion years ago.

By contrast, the new study found only one grain out of 66 with signs of shock, leading the study authors to the opposite conclusion: That because there was evidence of shock, there likely were active impacts still blasting Mars by that time. Both sources of evidence are from the same rock sample that could have been shocked by a local impact, Treiman says, so he’s wary of generalizing these effects to the whole of Martian history. “It all goes into how they interpret that small proportion,” he says.

This debate does have implications for the habitability of Mars, Treiman says, but it’s also involved in a bigger debate about what’s called the Late Heavy Bombardment–the existence of which has been a controversy since early lunar studies. This is the idea that after the chaotic formation of the solar system, just when things began to quiet down, there was a secondary period of major collisions that blasted the Earth, moon, Mars and other bodies with meteors and asteroids. The answers to these questions will have to wait.

But, Cavosie says, this provides a window into Mars’s history and “a wealth of new questions to follow going forward.”