Astrobiologists Alberto Fairen, and Dirk Schulze-Makuch have beef with environmental protection policies. Not here on Earth, that is, but on Mars, where rigid regulations from NASA’s Office of Planetary Protection are holding back potentially life-discovering research, according to the pair’s paper in Nature Geoscience today.

While humans can’t make it to Mars just yet, it’s possible that some microbial spacecraft hitchhikers can survive the journey and make their home on the Red Planet. In fact, it’s probable that they already have. Some Earth life might have also been transferred naturally through meteorites.

NASA’s Office of Planetary Protection would like to minimize the risk of bringing more life to Mars than we bargained for. Its goal is to “promote the responsible exploration of the solar system by minimizing the biological contamination of explored environment,” which seems like a pretty noble goal–the first rule of interplanetary camping is leave your site less Earth-y than you found it.

But Fairen and Schulze-Makuch take issue with the fact that missions exploring “special regions”–places that the Office of Planetary Protection determines could theoretically support either Martian or Earth life–face extra sterilization requirements to ensure that there’s no cross-planetary contamination. These strict guidelines–including working in clean rooms with special airflow requirements and sterilizing spacecraft using dry heat microbial reduction–they argue, make the search for life on Mars too expensive, and curtail exploration. (It’s unclear what kind of extra expense we’re talking, though this clean room price calculator from 2001 makes them seem fairly pricey, at least to build.)

Thus, the scientists recommend, we should cut back on the regulations governing sterilization for orbiter missions and some surface missions, and re-evaluate the sterilization requirements for rover missions seeking to discover life on a case-by-case basis.

“If Earth microorganisms can thrive on Mars, they almost certainly already do; and if they cannot, the transer [sic] of Earth life to Mars should be of no concern, as it would simply not survive,” they write.

Essentially, they say that it’s likely Earth life has already contaminated Mars through meteorite impacts over the past 3.8 billion years, or through past spacecraft visits before sterilization requirements were put in place.

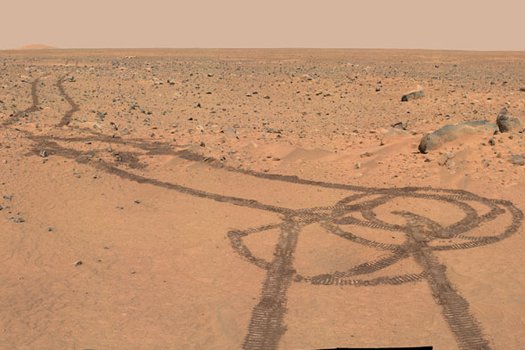

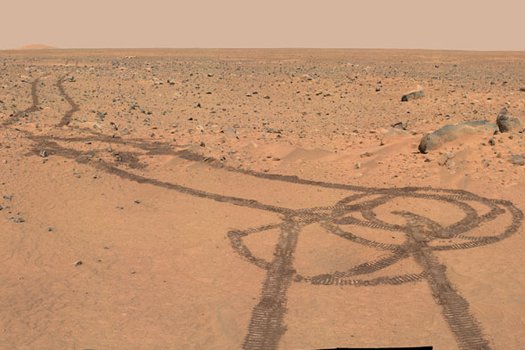

NASA’s spacecraft sterilization began with the launch of the Viking landers to Mars in 1975. Before being sent off into the great unknown, they were cleaned and then placed in essentially a giant casserole dish and baked for 30 hours at 233 degrees Fahrenheit to kill off any lurking microorganisms. But it’s uncertain if the unmanned Soviet missions to Mars and Venus during the period underwent any kind of sterilization. Some scientists say the missions probably deposited some organisms from Earth on those planets. More recently, the Mars rover Curiosity might have brought some Earth microbes on accidentally contaminated drill bits or on its wheels.

If the microorganisms that came to Mars over the past few billion years or during the Space Race didn’t survive, Fairen and Schulze-Makuch write, any new microorganisms probably wouldn’t either. If they did survive, well, the cat’s already out of the bag, and “it is too late to protect Mars from terrestrial life.” A little bleak. They still encourage cleaning spacecraft to prevent confusion between what microorganisms might be earthly in origin and which could be Martian.

And like any good argument, they make the case that scaling back requirements is all about your tax money: “As planetary exploration faces drastic budget cuts globally, it is critical to avoid unnecessary expenses and reroute the limited taxpayers’ money to missions that can have the greatest impact on planetary exploration,” they write. Fewer requirements, cheaper missions.

On the one hand, we’re all for making greater Mars exploration as easy as possible. But then again, we’re already pretty good at contaminating our own planet–maybe we should be strict about what we bring to another.