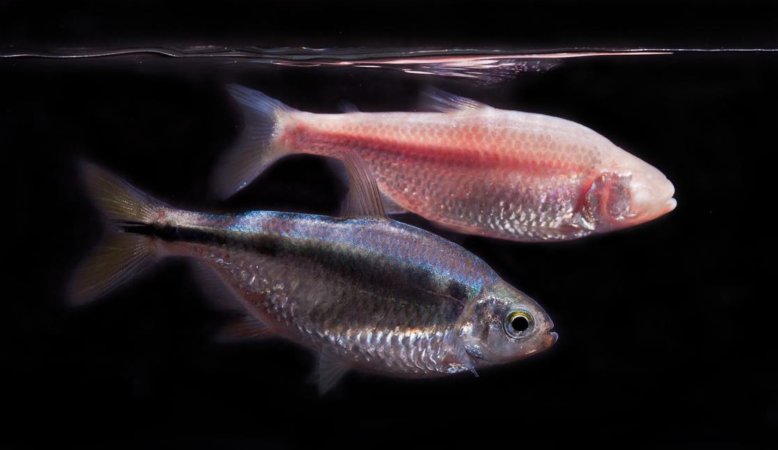

Climate change is causing glaciers around the world to melt, which in turn worsens sea level rise and disrupts ocean currents and coastal ecosystems. But for some fish, there may be a small silver lining.

Scientists used computer models to simulate how meltwater will feed new streams and lakes across western North America, and found that retreating glaciers could create thousands of miles of new habitat for Pacific salmon by the end of the century. Understanding where and when these piscine frontiers will emerge will be key for future conservation plans, the researchers reported on December 7 in Nature Communications.

“This showcases how climate change is fundamentally transforming ecosystems; what is now under ice is becoming a brand new river,” says Jonathan Moore, who leads the Salmon Watersheds Lab at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia and coauthored the new findings. “We can’t just manage for current salmon habitat, we also need to think about how we can manage for future salmon habitat.”

Glacial retreat does pose a threat to salmon in some areas. “It can decrease the air conditioner effect that glaciers have on downstream rivers, so rivers will be getting warmer during the summer,” Moore says. And as glaciers shrink, less seasonal meltwater is available to feed these rivers in summertime. However, when glaciers melt away from valley bottoms they can create new streams. “The rivers will be lengthening as the glaciers will be retreating up the valley, and other work has found that salmon can find and thrive in these newborn river systems,” Moore says.

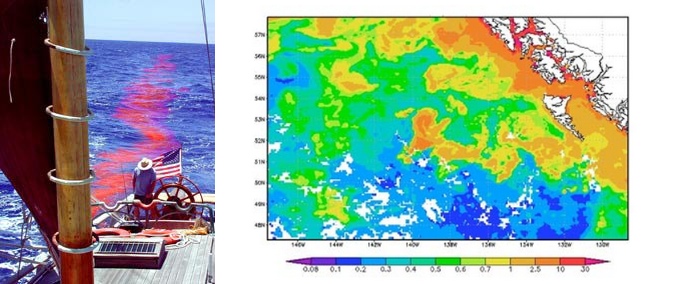

He and his colleagues investigated how this might play out in the coming decades across a 623,000-square-kilometer (240,542-square-mile) region stretching from southern British Columbia up into Alaska. About 80 percent of the glacier-covered territory in North America’s Pacific mountain ranges fall within the range of Pacific salmon, which support subsistence harvests and fisheries worth billions of dollars annually.

Led by Kara Pitman of Simon Fraser University, the researchers identified 315 retreating glaciers at the headwaters of existing streams that could create a habitat that salmon would be able to reach. The team then estimated when and where those glaciers would retreat under several climate change scenarios. “The next phase was to use predictions of what the land looks like underneath the ice…[to] imagine the future rivers in these future salmon habitats,” Moore says.

The researchers calculated that by 2100, Pacific salmon will have access to 6,146 kilometers (3,819 miles) of new streams. Much of this habitat will come from areas with large, low-lying glaciers near the coast, such as the Gulf of Alaska and Copper River.

[Related: Salmon are dying off and your car tires might be to blame]

The team also explored which parts of the aquatic network would provide suitable habitat for the fish to spawn and rear young salmon, based on the expected steepness of the stream channels. They found that about 1,930 kilometers (1,199 miles) of the burgeoning streams could offer gently sloping conditions ideal for the salmon.

As glacier ice disappears, more of the northern landscape will become available to mining and other industries. Forecasting where new salmon habitat is likely to open up may allow researchers to identify areas in need of protection, the researchers concluded.

However, Moore says, this will be a complicated undertaking. He and his team estimated how much potential habitat melting glaciers could create, but didn’t analyze how temperature and other environmental conditions could render new streams more or less inviting for the salmon.

Another complication is that salmon don’t spend all their time in freshwater habitats; they’re also tied to the sea. “If the ocean is increasingly unsuitable because of the warming that has created new freshwater habitats, that will not lead to more salmon populations,” says Peter Westley, an associate professor in the College of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. Westley is a co-leader of the Salmon Science Network Initiative, which provided funding for the research, but wasn’t involved directly in the current study. “You need both suitable ocean and available and suitable freshwater habitats.”

Moore wants to make it clear that the research doesn’t mean salmon will thrive as Earth warms. Salmon are facing many climate-related burdens, including marine heat waves, ocean acidification, and extreme floods and droughts. “The paper does not suggest that climate change is good for salmon,” Moore says. “It’s possible that these local opportunities might be overshadowed by large-scale declines in salmon populations.”

And even if salmon do move into new areas where glacial ice has waned, there will be consequences for people who depend upon the fish.

“The shifting distribution of salmon, while good for the salmon, does not address those really stark and pressing societal and cultural issues of the loss of salmon in certain rivers,” Westley says. “That does not help the person that’s on their river and seeing their salmon disappear because it’s too warm.”