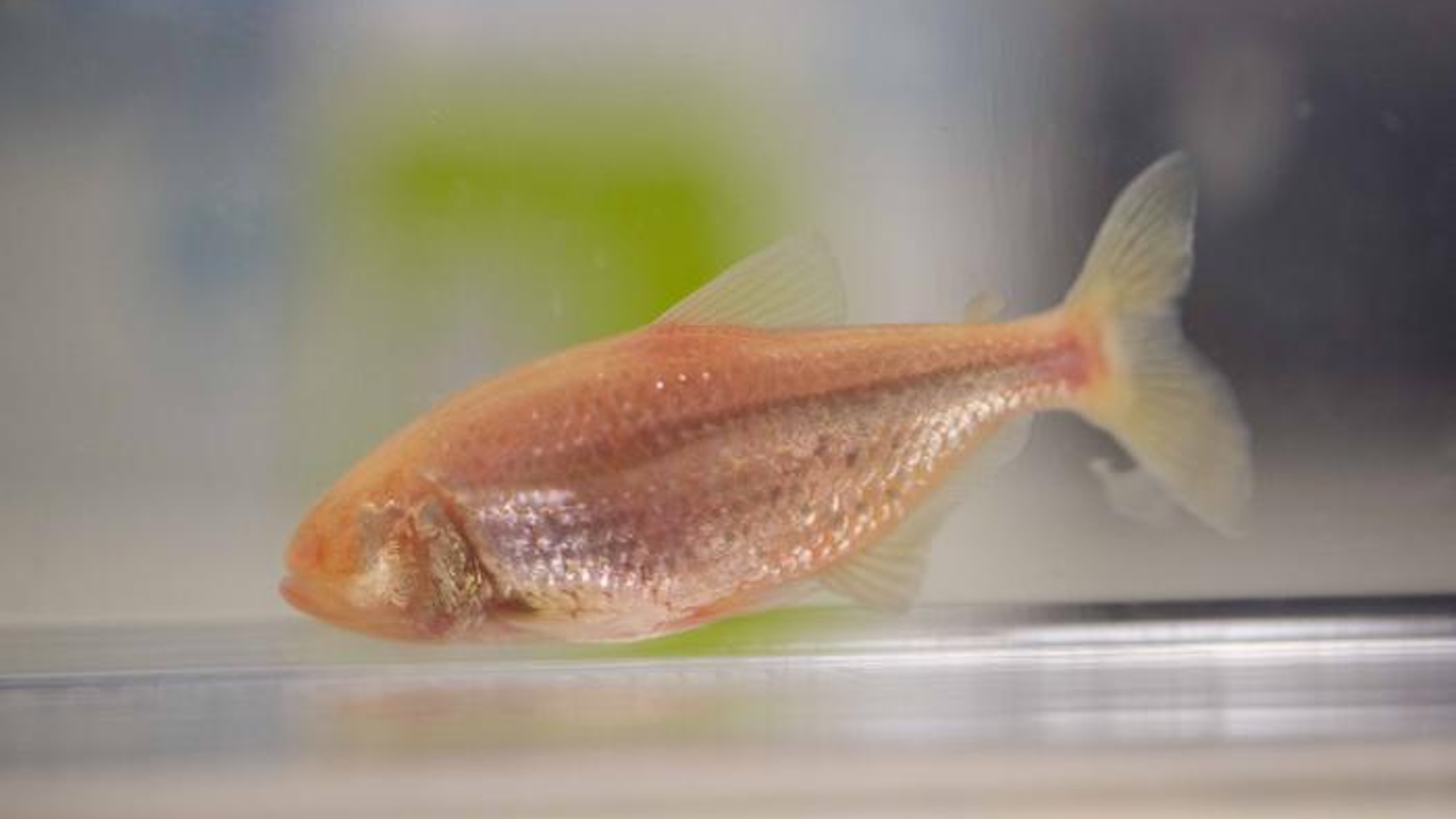

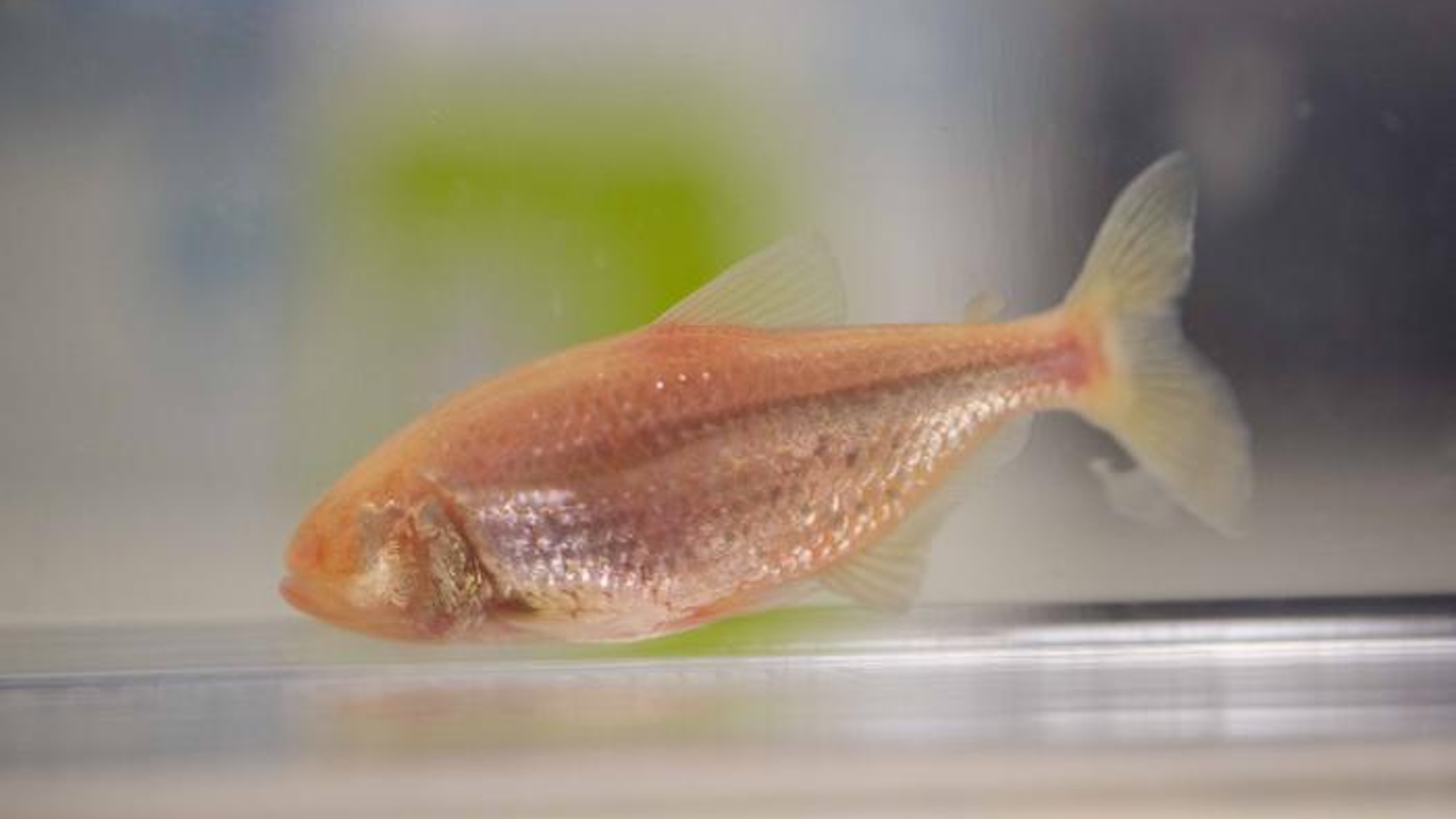

Despite belonging to the same species, there are technically two kinds of cavefish in northeastern Mexico: those with extremely large eyes and those with no eyes at all. But a lack of vision organs isn’t the only unique physical adaptation found in the “blind cavefish.” They also have evolved extra taste buds—just not in their mouths. Now, researchers are beginning to understand when and why this evolutionary adaptation happens.

Biologists first learned that blind cavefish in Mexico grow extra taste buds on their heads and chins back in 1967. Since then, however, scientists have spent little time investigating the evolutionary trait. As detailed in a study published on August 6 in the journal Communications Biology, a team from the University of Ohio, Cincinnati, recently traveled to Mexico to find out more about the evolutionary journey of blind cavefish (and their taste buds).

“Regression, such as the loss of eyesight and pigmentation, is a well-studied phenomenon, but the biological bases of constructive features are less well understood,” senior author and UC Cincinnati professor of biology Joshua Gross said on August 15 in an accompanying university profile.

To begin understanding these small, semi-translucent fish, Gross and his team focused on two separate populations of Astyanax mexicanu in Mexico’s Pachón and Tinaja cave systems. After studying their development cycles beginning at birth, researchers discovered blind cavefish possessed similar numbers of taste buds as their surface brethren until they reached around five months old. At that point, the eyeless variations started to grow additional taste buds across their heads and chins through maturation at 18 months, then well into adulthood. Given that cavefish lifespans can span five or more years, Gross theorizes that blind cavefish may develop even more over time. With the extra taste buds, these cavefish obtain a much more precise sense of taste compared to their eyed variants found outside caves.

[Related: How the archerfish evolved to shoot insects.]

The appearance of external taste buds also seems to correlate to when cavefish transition from a diet of live food sources to other options—primarily bat guano (aka poop), given the sparse food options in caves.

“Despite the complexity of this feature, it appears that more taste buds on the head are controlled mainly by only two regions of the genome,” said Gross.

The novel discoveries can potentially offer new avenues to study how vertebrates evolved their particular sensory organs. For now, however, researchers still aren’t sure what adaptive or functional relevance the additional taste buds provide the blind cavefish. To pursue this line of study, Gross and his team are now studying how the fish react to various flavors such as sweet, sour, and bitter tastes.