These days, the Jezero crater on Mars is an arid, barren depression. But it was a very different place billions of years ago, images taken by NASA’s Perseverance rover have revealed.

Scientists examined layers of sediments and rocks lodged in the sides of the crater, and determined that it was once a placid lake and river delta. That ultimately changed when powerful flash floods struck the crater, pummeling it with boulders swept in from the rim or beyond.

The geological history of the Jezero crater could help scientists understand how the Red Planet changed from being wet and possibly habitable into a harsh desert world. It also provides a compelling target to search for traces of life, says Benjamin Weiss, a planetary scientist at MIT. “Definitely we hit the jackpot here,” says Weiss, whose team reported the findings on October 7 in Science.

The surface of Mars was once dotted with massive crater lakes. The 28-mile Jezero crater held one such lake around 3.7 billion years ago. Scientists have previously detected fan-shaped structures along the edges that resemble deltas on Earth, suggesting that ancient rivers carried water, sand, and mud into the crater.

“We know that we’re dealing with a lake and river system; these tend to be very habitable on Earth,” says Amy Williams, an astrobiologist at the University of Florida and coauthor of the study. That made the Jezero crater an inviting site for the Mars 2020 mission, which deployed the Perseverance rover to explore environments that could have hosted microbial life.

[Related: After a few hiccups, NASA’s Perseverance begins its main missions on Mars]

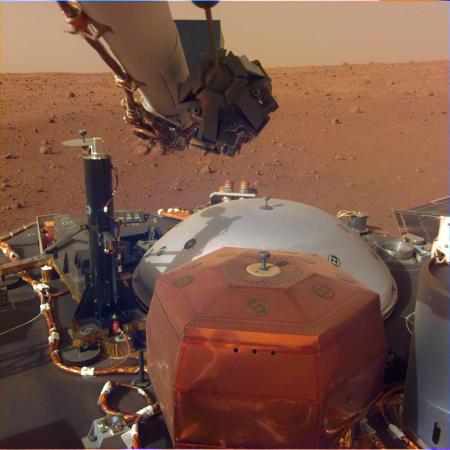

On February 18, Perseverance touched down on the floor of the crater, several kilometers from the relatively well-preserved westernmost delta. Over the next three months, the rover stayed put while researchers made sure its instruments and software were working. This gave Perseverance plenty of time to snap pictures of the main fan and an isolated hill the team called Kodiak butte about a half mile south. Leftover “islands” like Kodiak indicate that the delta was much larger in the past, before it was worn down and fragmented by billions of years of erosion, Weiss says.

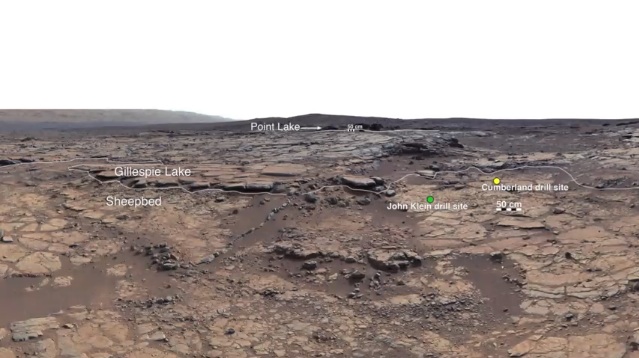

When he and his team analyzed the images of both sites, they observed sloped layers of sediments.

“These delta deposits tell us that the lake levels within Jezero changed a lot through time, implying that the climate was warm enough (at least in this region) to allow large rivers to flow and fill a lake while forming a delta,” Stefano Nerozzi, a planetary geologist at the University of Arizona who was not involved in the research, told Popular Science in an email.

When a river flows into a lake, heavier objects are the first to settle, Williams says. Lighter materials tend to travel farther from the mouth of the river. She and her colleagues were particularly excited by gently dipping beds of fine-grained sediments most visible on Kodiak butte.

On Earth, such sediments are prime places to look for evidence of past life, says Tanja Bosak, a geobiologist at MIT and another coauthor of the findings. For one thing, they tend to be deposited under gentle conditions. “If there’s any life, nothing grinds it up; if you have boulders bouncing, that will not do good things to your life,” Bosak says. “Another reason is these sediments tend to be chocked full of clay minerals, and clay minerals act like natural sponges for organic matter.” Clays smother this precious cargo and preserve it from sunlight and other hazards for millions of years, she says.

The team also noticed boulders several feet in diameter sitting atop the older sediment layers of the delta. “These rocks are not the kind of thing that are deposited in a quiescent, low-energy environment like a lake with a lazy river flowing into it,” Weiss says. “To carry such big rocks, you need really intense energetic flows like you’d expect from flooding events.”

[Related: Mars may be too small to have ever been habitable]

Many of the boulders have “nicely rounded” sides, Williams says. “This tells us that they actually have undergone long-distance travel from wherever they came from to be deposited here,” she says. The boulders might be pieces of crater rim that were dislodged and washed into the delta. Alternatively, the boulders might be even older rocks from outside the crater, carried from perhaps as far as 40 miles away, Weiss says.

It’s not clear yet what caused the small-scale flash floods that arrived late in the crater lake’s history. “Maybe we’re capturing the transitioning [of Mars] to the colder and drier conditions of today,” Weiss says. “Right now we don’t know whether this is a sign of the global climate change on Mars or not.”

This question could be answered over the next several years as Perseverance takes a closer look at the rocks and sediments strewn about the delta, and gathers samples that will hopefully be brought to Earth.

The samples could also be researchers’ best chance yet at identifying signs of past life on Mars. “Finding well preserved lower delta deposits means that we have sediments with the highest preservation potential for organic matter, at least by Earth’s standards,” Nerozzi says. “This is definitely the right place to be to look for traces of possible ancient life on Mars.”