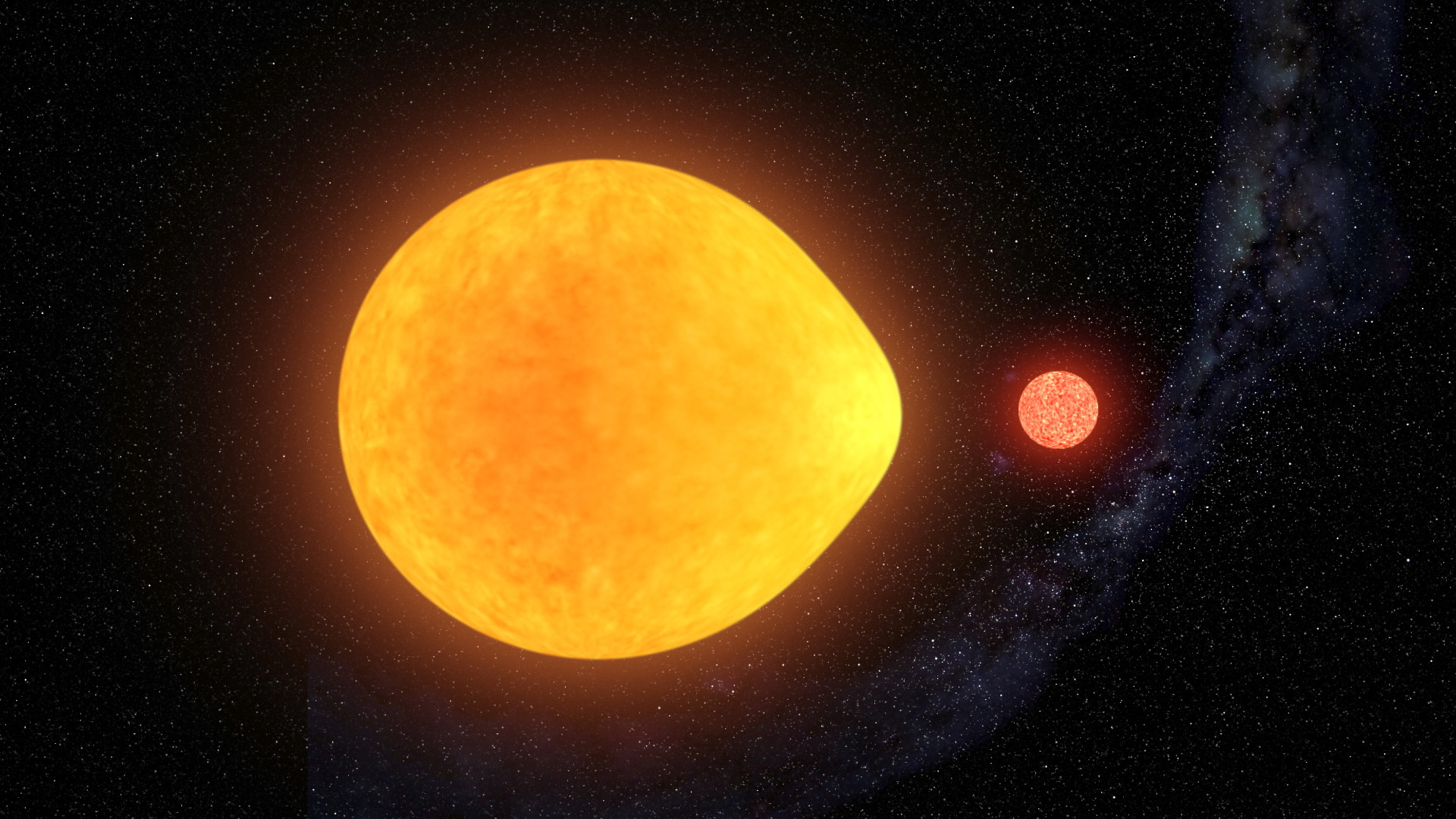

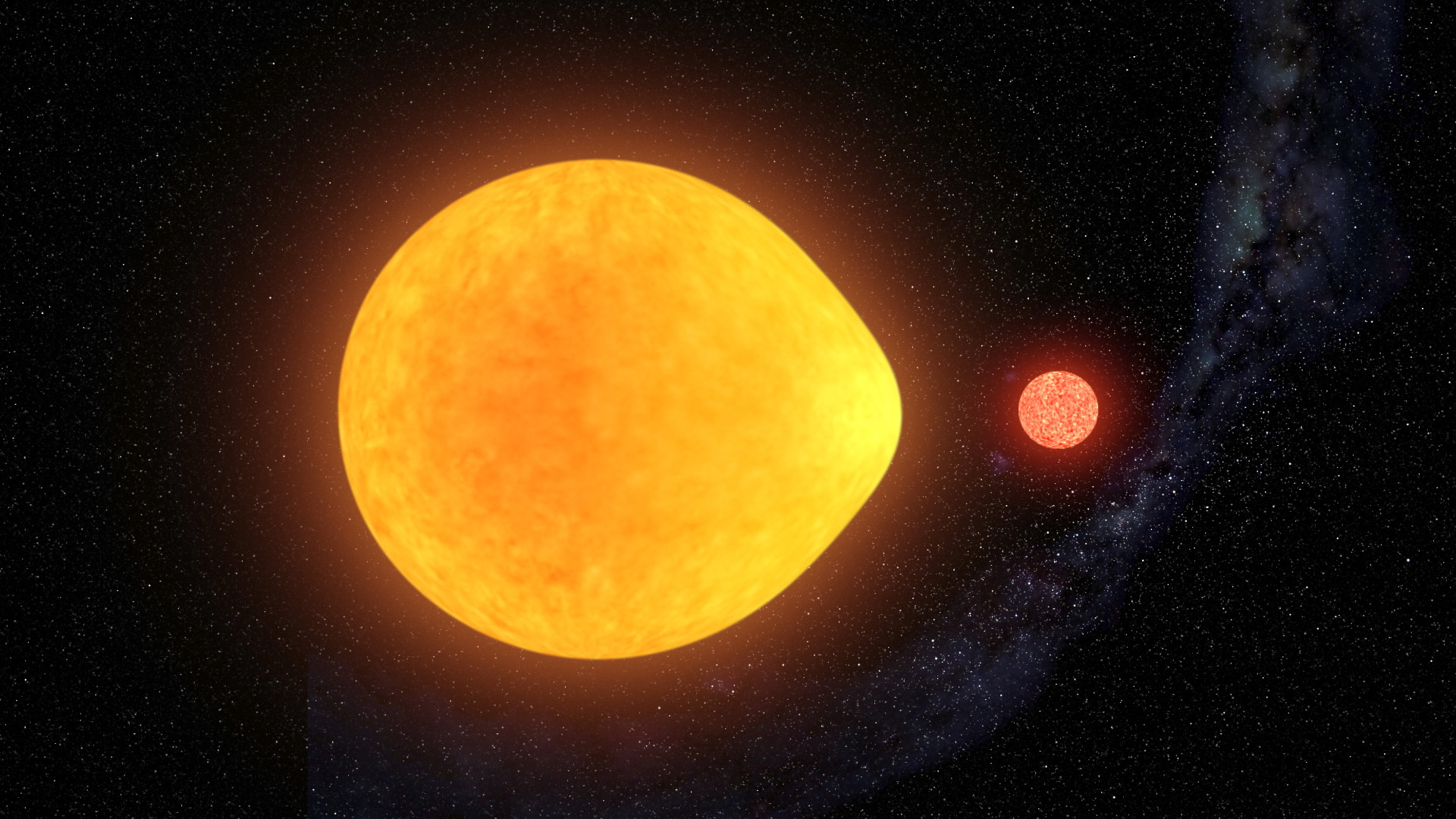

If any beings live in the solar system HD 74423, their young ones would sketch daytime scenes quite differently than human children do. Where we draw one sun, they’d draw two. And where we draw our star as a round orb, they’d likely draw one of their suns as a bulging teardrop. Gifted animators might even capture the bump’s motion as it stretches toward and recedes from its companion over a matter of hours.

This star’s outlandish shape and behavior are prominent enough to be detected from Earth, 1,600 light years away, astronomers announced on Monday with a publication appearing in Nature Astronomy. Theorists have long suspected such a system was possible, but HD 74423 is the first confirmed binary containing one star whose pulses reach out toward its partner. And because it represents a new way for two stars to interact, it could also help astrophysicists better understand what makes some stars ripple and contort while others stay largely motionless.

“Wow,” wrote Gerald Handler, an astronomer at the Nicolaus Copernicus Astronomical Center in Poland in an email to a colleague upon first seeing data containing the flickers of the bulging star. “I have never seen something like that before.”

Our sun appears pretty unchanging day after day, but that’s because we’re looking at it from so far away. Up close, boiling blisters on its surface reveal the star’s more variable, liquid side. Other stars experience internal churning and bubbling too, and under the right circumstances they can positively pulse with activity. (The field of asteroseismology uses these reverberations to infer what’s going on deep beneath a star’s surface.)

One dramatic case of stellar throbbing is the type of star known as a “heartbeat star.” They occur in pairs with elliptical orbits that bring the two stars alternatively nearer together and farther apart. When the partners draw close, they give each other an extra gravitational squeeze that then relaxes as they pull away. Overtime these regular squeezes cause one or both stars to undulate—stretching out like an egg and then collapsing back into a squat orange-like shape.

HD 74423, the new discovery, is a pair of stars that whip around each other in a roughly circular orbit once every 38 hours. They keep a pretty constant distance from each other, Handler says, which means they don’t fit the definition of heartbeat stars. Their behavior is even weirder.

Since the partners orbit each other so closely, one partner’s gravitational pull drags the surface of the other toward it, stretching the star out into a persistent teardrop shape. And the teardrop pulsates inward and outward toward the companion. In an upcoming publication, the astronomers will propose that this pulsation takes place because the tapered part of the star is “fluffier,” Handler says, and this fluffiness amplifies natural ripples from deeper in the sun in the direction of the partner.

Astrophysicist Donald Kurtz of the University of Central Lancashire in the UK first predicted that such a setup might be possible decades ago, but no astronomer had located one until now. “I’ve been looking for a star like this for nearly 40 years and now we have finally found one,” Kurtz said in a press release.

And they almost didn’t find it. NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), which focuses on looking for exoplanets, made the discovery possible. In HD 74423, the companion star blocks light from the teardrop star much as an exoplanet might, but not similarly enough to get picked up automatically by NASA’s planet-hunting algorithms.

Instead, two volunteer citizen scientists—Robert Gagliano and Tom Jacobs—independently noticed anomalous flickers in the light coming from HD 74423 as the teardrop grew, shrunk, and turned. They flagged the system as a potentially interesting target, and Handler confirmed the details by observing it more closely with the South African Astronomical Observatory. “Without those guys we probably would never have found it,” he says.

And now that they have it, the next step is to look for more. While this case is largely an astronomical curiosity, finding other pulsating teardrop stars could help answer a larger question in the study of stellar vibrations: why do some stars quake while others remain still? Even in the twin stars of HD 74423, only one appears to be quivering. Astronomers would also like to figure out more about how much oomph is required to orient the pulsations in a given direction, and what the system will look like in billions of years—all questions that require deeper insight into the structure and behavior of the balls of plasma that dot our universe.

“We just need to keep looking,” Handler says. “We have more questions right now than answers.”