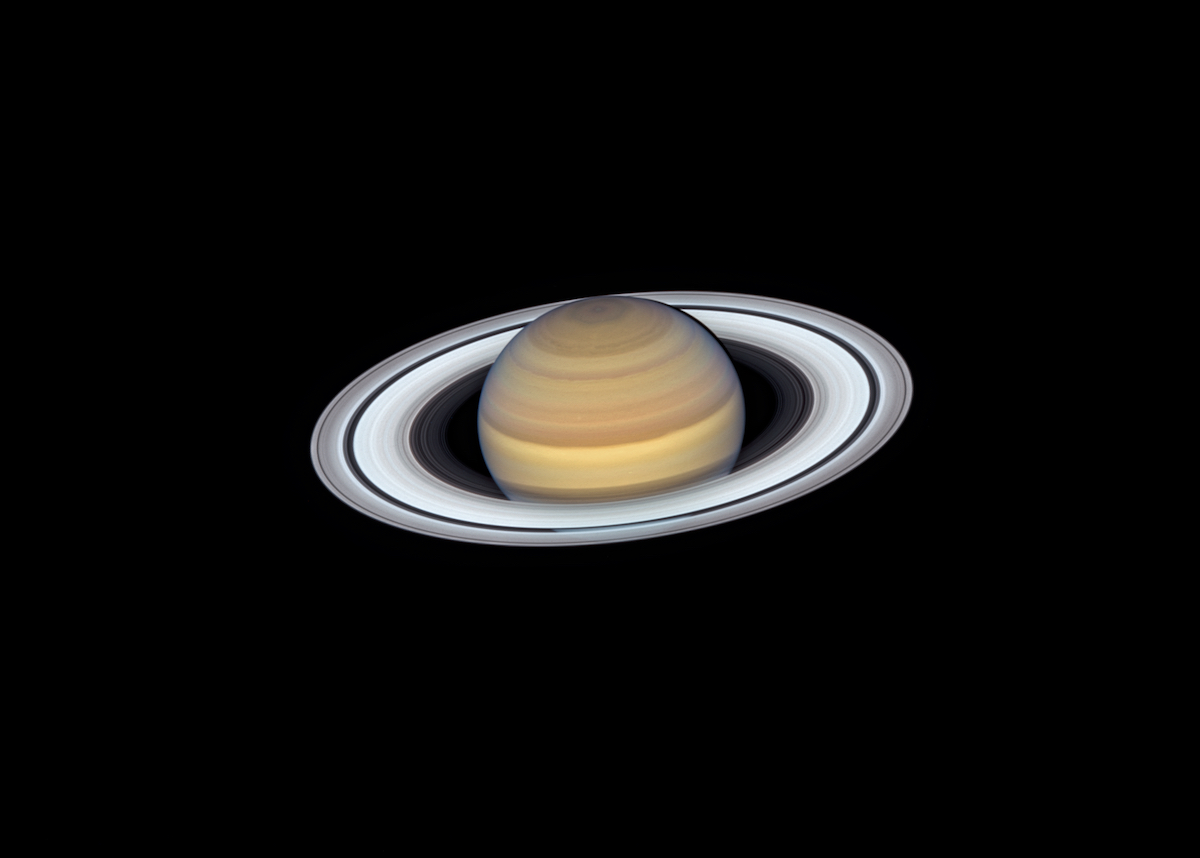

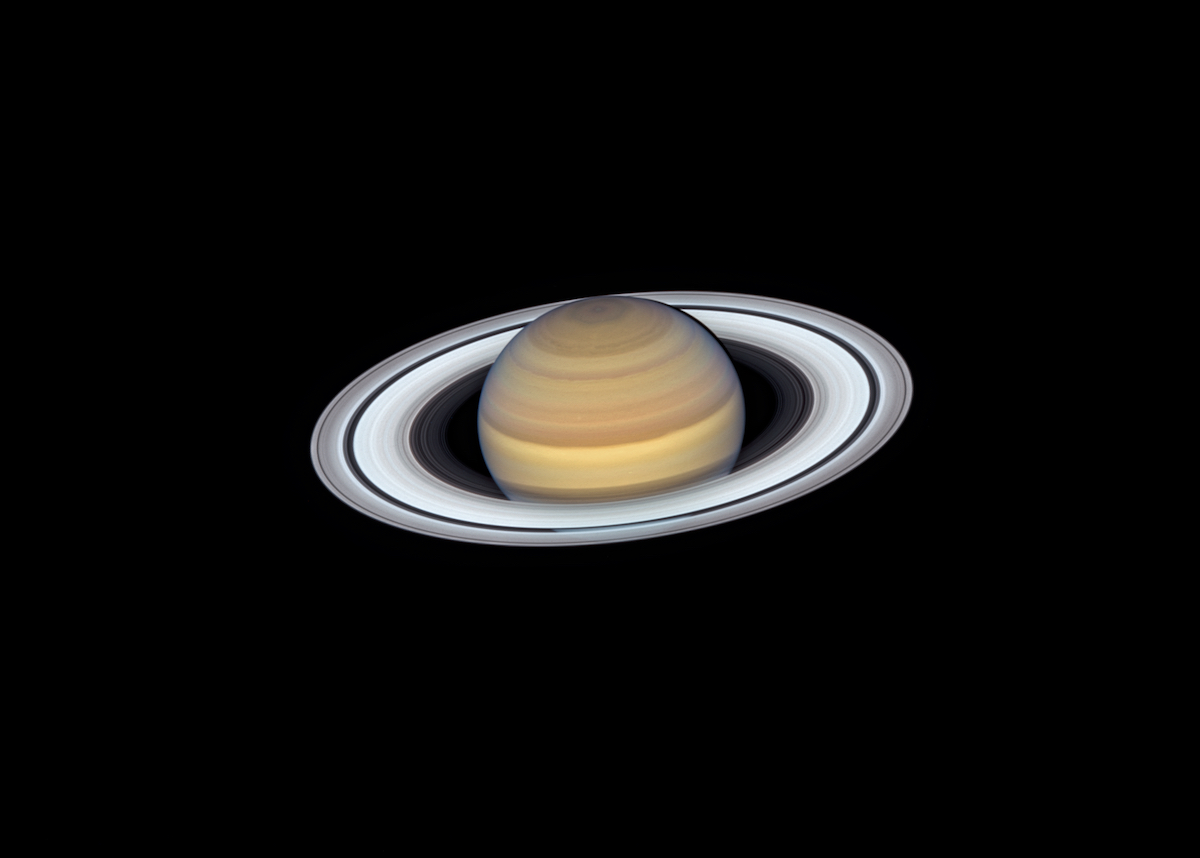

The colorful rings that swirl around Saturn’s mid-section aren’t the only characteristic that makes it stand out among the planets of our solar system. Called a “belted giant,” the second largest planet is also spinning at a bit of a tilt: a 26.7-degree angle relative to the plane in which it orbits the sun, to be exact (compared to Earth’s 23.4 degree angle).

So why does the belted giant lean? Astronomers surmise that Saturn’s tilt is due to gravitational interactions with its planetary neighbor Neptune. Saturn’s tilt precesses (a circular motion similar to a spinning top) at nearly the same rate as the orbital spin as Neptune.

A new study published today in the journal Science finds that Saturn and Neptune’s gravity may have once been in sync, but Saturn has since escaped Neptune’s pull due to a missing moon.

The team first modeled the interior of Saturn and found a distribution of mass that matched its gravitational field. This newly identified moment of inertia placed Saturn close, but just outside resonance, with Neptune. “Then we went hunting for ways of getting Saturn out of Neptune’s resonance,” said Jack Wisdom, professor of planetary sciences at MIT and lead author of the new study, in a press release.

[Related: Here’s why Saturn’s ‘ocean moon’ is constantly spewing liquid into space.]

The team ran simulations to determine the characteristics of a satellite (properties such as its mass and orbital radius) and what it would be required to knock Saturn out of the resonance or path. Enter a mysterious, previously unknown moon of Saturn.

The authors suggest that Saturn (currently home to 83 moons) once had at least one more in its orbit that they named Chrysalis, which was about the same size as Iapetus, Saturn’s third-largest moon. The research suggests that Chrysalis and its moon (or satellite) siblings orbited Saturn for several billion years, pulling and tugging on the giant planet in a way that kept its tilt (also called obliquity) in resonance with Neptune.

Sometime between 200 and 100 million years ago, Chrysalis entered a chaotic orbital zone, and experienced a number of close encounters with the moons Iapetus and Titan, and eventually came too close to Saturn in a “grazing encounter,” which means the moon came into some contact with another object in space.

This celestial swipe broke the moon into pieces with enough force to remove Saturn from Neptune’s grasp, leaving it with its present-day tilt. It’s also possible that a fraction of Chrysalis fragments could have remained suspended in orbit, eventually breaking into small icy chunks to form the planet’s signature rings. The rings were previously estimated to be about 100 million years old, much younger than Saturn’s suspected age of about 4.5 billion years.

“Just like a butterfly’s chrysalis, this satellite was long dormant and suddenly became active, and the rings emerged,” said Wisdom.

[Related: These gorgeous photos of Saturn’s rings are Cassini’s ‘Grand Finale.’]

The new study used some of the latest observations taken by Cassini in its Grand Finale: the concluding phase of the 20 year-old mission when the spacecraft made an extremely close approach to precisely map the gravitational field around Saturn. This data helped the team pin down Saturn’s moment of inertia and determine the gravitational field and the planet’s mass.

“It’s a pretty good story, but like any other result, it will have to be examined by others,” Wisdom said. “But it seems that this lost satellite was just a chrysalis, waiting to have its instability.”