Artemis 1, a massive research craft intended to test whether the Space Launch System (SLS) rocket is capable of sending astronauts to the moon, failed its first launch attempt early Monday morning. Despite the engine bleed that stopped the countdown, NASA continues to troubleshoot the mission and could try again Friday September 2 at the earliest.

“This is an incredibly hard business,” said Mike Sarafin, the mission manager for Artemis, during a NASA conference about the scrubbed launch on Monday. “We’re trying to do something that hasn’t been done in over 50 years, and we’re doing it with new technology.”

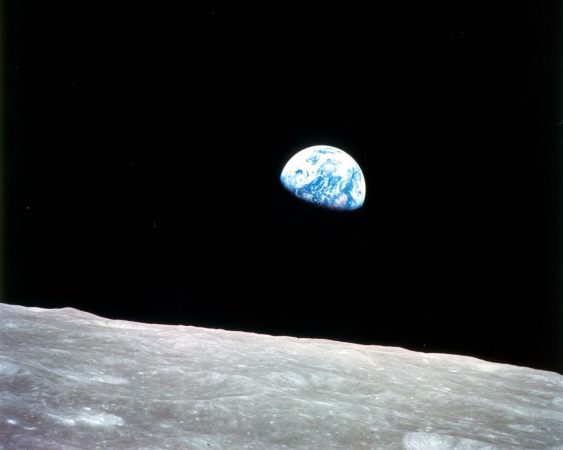

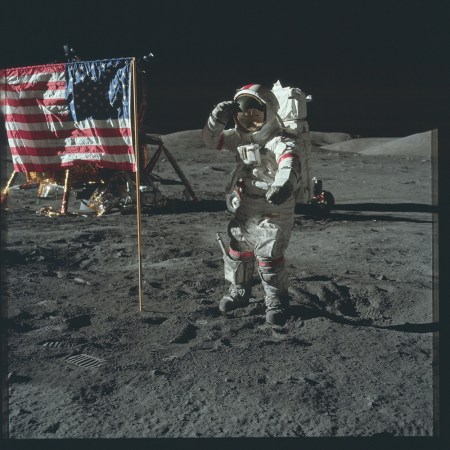

The last time humans stepped on the moon was during the Apollo 17 mission in 1972. If and when Artemis 1 is able to launch, the first flight will conclude a half a century hiatus and a new era of long-term human exploration on Earth’s satellite. Over the next decade the Artemis program will roll out missions to establish a permanent lunar outpost. And NASA already has their eye on an ideal spot: the moon’s untrodden south pole.

Artemis 2, the second scheduled flight and the first crewed flight of the Artemis program, is currently slated for launch in May 2024. The first batch of lunar astronauts won’t be making landfall. Instead they’ll be embarking on an 8 to 10 day flyby of the satellite before making their way back to Earth. If all goes well, Artemis 3, the second crewed flight of the program, will launch in 2025 for NASA’s well-awaited return to the lunar surface. Once astronauts do reach their destination, the crew, which includes the first female and first astronaut of color on the moon, will set down for about a week at one of 13 potential landing sites.

[Related: The elements we might mine on the moon]

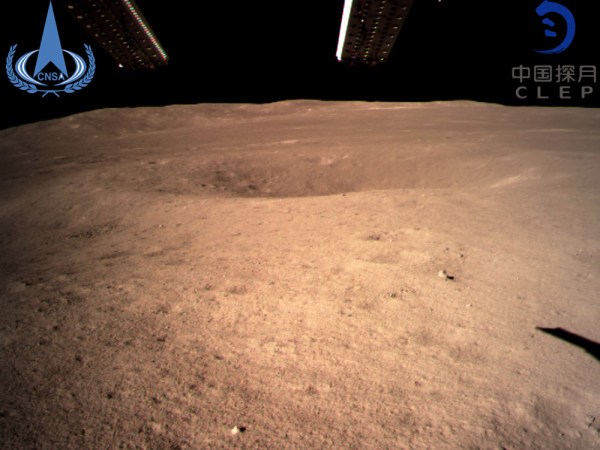

Even as humans set foot back on the moon, the Artemis crew will head to vistas beyond those initial strolls of the Apollo missions 50 years ago. All of the possible lunar locales lie near the moon’s south pole, an area of our satellite that until now, has been drenched in mystery.

“Some of the oldest rocks that we know to exist on the moon could be found there,” says Noah Petro, chief of planetary geology at NASA and one of the scientists who helped identify these potential regions. The moon’s south pole is a very different environment than what Apollo astronauts explored; all their missions took place near the equator. Petro says that depending on where they go, Artemis astronauts could be trudging across moon rocks that are at least 4.3 billion years old.

“Figuratively, they’ll be transported back in time, to an early era of our history,” Petro says. And it’s that exploration that could reveal not just the history of the moon, but the history of the solar system, as well as the universe, he says.

[Related: We now have proof that plants can grow in moon dirt]

Because of the tilt of the moon’s axis, the south pole is rife with both light and shadowed regions, which means some areas could be harder to explore than others. But it is rich with resources, such as lunar ice water, which could be used for life support systems and fuel—supplies that would be extremely helpful to NASA’s long-held goal of creating a habitable moon base. Each region is also home to its own unique geologic features and will be able to provide near continuous sunlight throughout the duration of the Artemis 3 mission. Building a base in a sunny spot is particularly imperative as solar energy provides a power source, and would help astronauts weather the moon’s freezing temperatures.

As each site is connected to a potential launch window, it’s hard to guess exactly which of the 13 areas will bear the next lunar flag, especially with NASA’s history with scrubbing launches in favor of astronaut’s safety. Still, past flights—launched or scrubbed—are lessons for current and future mission scientists. Petro even notes that while earlier generations learned much from Apollo, people have been asking new questions in the decades leading up to Artemis.

By teaching ourselves how to conquer the moon once more, we’re in a position to do far greater things both on Earth, and in space.

“It’s a very exciting moment in our history,” he says. “We did not answer everything when we first explored, but now we have that place to start.”