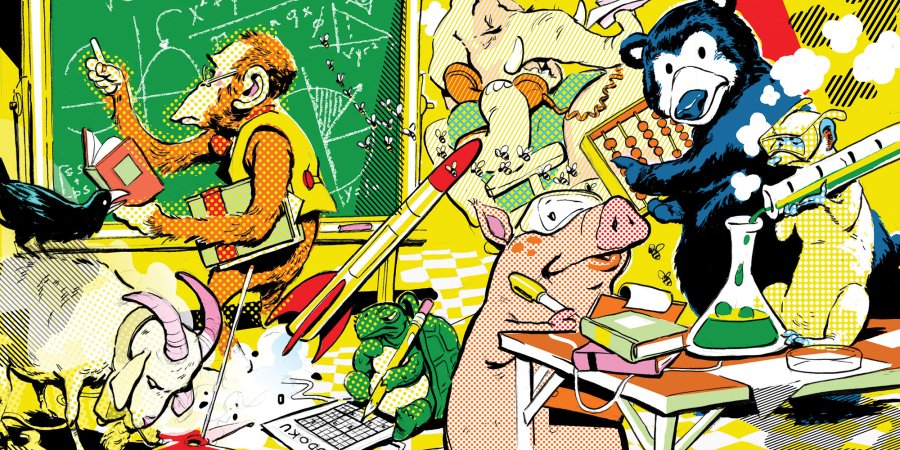

Here’s the buzz: bees are brilliant. And not just because they are a vital part of our ecosystem. Bees are also very clever—and apparently capable of learning one of the basic fundamentals of football.

In a new study published Thursday in Science, researchers at the Queen Mary University of London demonstrated that bees could learn to do a totally unnatural task—moving a ball into a specified area—easily and quickly, especially if they were shown how to do it by a plastic bee, or a bee that had been previously trained to do the task.

In the study, researchers tested bumblebee intelligence by teaching them to play a rudimentary version of single-player soccer. A bee pushed a bee-sized ball into a ‘goal’ area in the center of a circular pattern in order to get a reward of sugar water. They learned fast.

The research builds on previous experiments from the same lab, which taught honey bees to tug a string to get to a reward.

But while tugging a string to get to food isn’t that different from actions a bee might take in the wild to get honey, moving a ball into a goal is a totally foreign concept to the little critters.

“This is far removed from anything they have ever seen or had to do. There are no flowers that require a bee to move a ball or moving object in with them,” says study co-author Clint Perry.

“Insects continually surprise us with how smart they are, and this is another really cool chapter in that story,” says Margaret Couvillon, a honeybee researcher at Virginia Tech who was not involved with the study.

“For me, the social dimension of it; that the bees can learn this non-natural task better when it is demonstrated, is almost more interesting than the fact that they’re learning a non-natural task itself,” Couvillion says. In the study, the bees learned how to move the ball more quickly when they were shown a model plastic bee moving the ball, and faster still when a bee that had already been trained showed the newcomer the ropes.

The social learning shows how knowledge—even involving a new technique or skill—can be quickly transmitted from bee to bee.

Not that bees aren’t smart on their own. There were a few phenomenal bees who figured out what to do as the experiment was first being demonstrated to them. (We expect those naturals will be shoo-ins for the first inter-hive Bee-Ball competition.)

Many of the bees also managed to demonstrate their smarts by improving on the techniques displayed to them. While demonstrator bees and models always started with the ball furthest from the newbie bee, when faced with a choice of balls, the bees didn’t automatically gravitate towards the one they’d witnessed moving in the demonstration. Instead, they took a risk and went for the ball closest to them. They were also able to solve the puzzle even if the balls were a different color.

“This is really pushing the idea and solidifying the idea that small brains aren’t necessarily simple; these small brains can solve complex tasks,” Perry says.

While bee brains are orders of magnitude smaller than human brains—a million neurons to over 100 billion neurons—they can still solve problems quickly, even in very unfamiliar circumstances.

“I think that anyone working in this area wouldn’t be surprised at how smart they are. For most of us, that’s why we fall in love with them in the first place,” Couvillon says. “We know they’re smart, but this shows a new way to get at how flexibly smart they can be.”