Officials at the White House announced a new space policy directive last week, focused on managing the increasing numbers of satellites that companies and governments are launching into space. Space Policy Directive-3 lays out general guidelines for the United States to mitigate the effects of space debris and track and manage traffic in space. The news was announced last week at the meeting of the National Space Council, but was quickly overshadowed by President Donald Trump’s surprise announcement indicating that he wished to establish an independent military branch focused on space.

As the name implies, this is the third space directive issued by the current administration since the reinstatement of the National Space Council in June 2017. The first directive pushed for humans to return to the moon. The second indicated a desire for an updated regulatory framework to manage the increasing volume of commercial spacecraft.

“To remain the flag of choice for commercial space activity, it is imperative that the United States lead this effort and enhance U.S.-based space activities. Future commercial activities in space—journeys to Mars, asteroid mining, and space tourism—will depend upon companies’ access to accurate and usable data that manages traffic and protects their equipment,” Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross wrote in a Washington Post op-ed.

Trump signed the directive—which includes new regulations about debris and space traffic—at the meeting last week, after telling the Council and assembled audience members to not “get too carried away” with making new regulations.

The third directive formalizes changes announced in April at the last meeting of the National Space Council. It sets the stage for the Department of Commerce to take over the management of traffic in space from the Department of Defense, though the latter will still keep the official catalogue of all objects in space. The FCC will still be in charge of making sure that newly launched satellites don’t use radio frequencies that would interfere with existing satellites. There is no firm timeline for the new traffic management system to go into effect, but it should be over the next few years.

“What we hope to do is have a more user-friendly approach at the Commerce Department. Right now, the DOD has been, I think, burdened by taking on not only its national security activities but also interfacing with civil and commercial components that have increasing need for SSA data and space traffic management capabilities,” Scott Pace, Executive Secretary of the National Space Council, said in a press briefing. “This is not going to happen overnight. But what we hope to see is that people would get more rapid and more accurate information on when they can launch, more flexibility in their launch windows going up; that they can, if we do well over space traffic management in the years, that we’ll see satellites having to maneuver less often because of potential collision risk.”

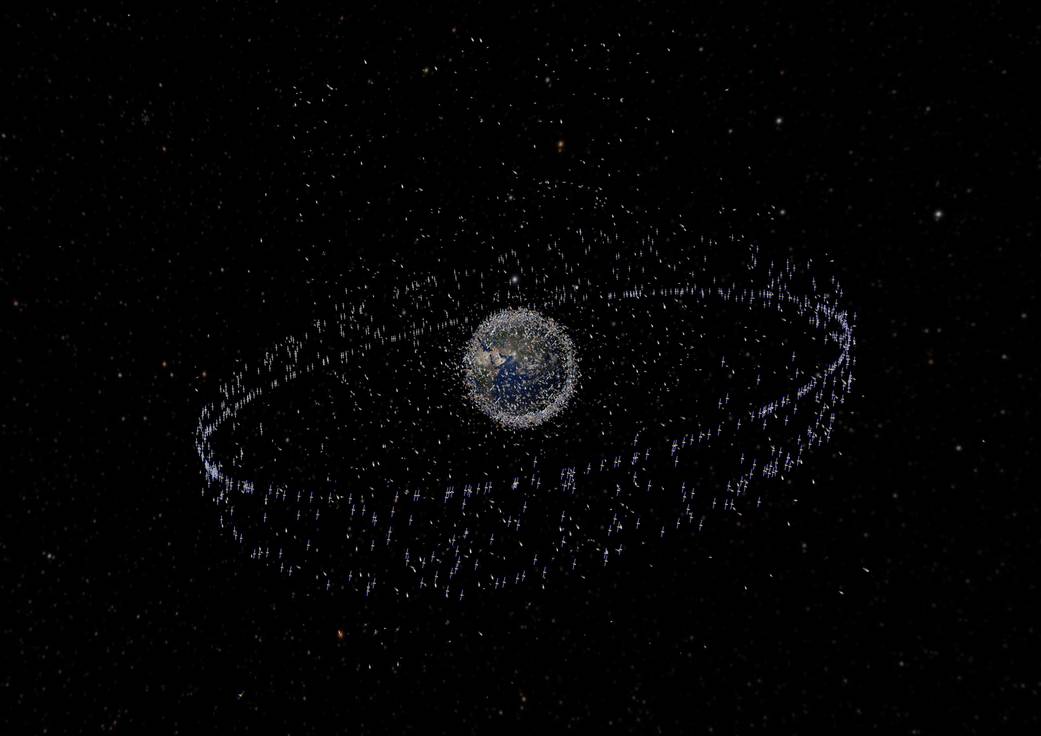

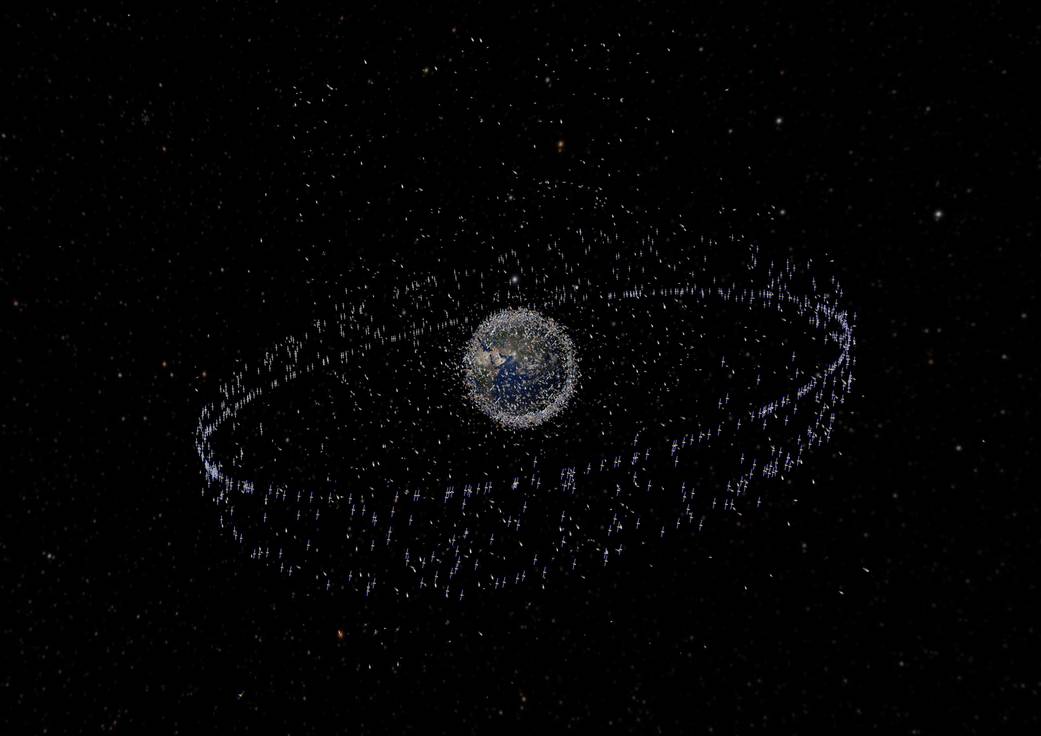

If that all sounds complicated, that’s because it is. Space, especially the space directly around our planet, is getting more crowded as more governments and companies launch satellites. One impetus for the directive is that companies are already starting to build mega-constellations, comprising hundreds or thousands of satellites with many moving parts among them.

With so much stuff in space, and a limited area around our planet, the government wants to reduce the chances of a collision. Two or more satellites slamming into each other could create many more out-of-control bits that would pose even more hazards to the growing collection of satellites in space.

And it’s not like this hasn’t happened before. In 2009 an old Russian craft slammed into an Iridium communications satellite, creating a cloud of hundreds of pieces of debris and putting other hardware at risk. Writing at Wired, journalist Sarah Scoles reports that the DoD and NASA currently track about 24,000 objects in space, and in 2016 the Air Force had to issue 3,995,874 warnings to satellite owners alerting them to a potential nearby threat from another satellite or bit of debris.

That’s why the latest directive also includes directions to update the current U.S. Government Orbital Debris Mitigation Standard Practices, which already require any entity that launches a satellite or spacecraft to strenuously analyze the likelihood that any of their actions, from an unexpected failure or normal operations, will create more space debris. It includes accounting for any piece of debris they plan to release over 5mm that might stay in orbit for 25 years or more. It might seem surprising to think about an item staying in space for that long, but the ISS turns 20 in November, and it’s relatively young. The oldest satellite still in orbit—Vangaurd 1—turned 60 this March.

Since there is so much debris in space, why don’t we just start getting rid of the older stuff as we launch the next generation of satellites? Groups are already working on developing technology that would gobble up or capture space debris before it caused serious damage. But as it turns out, that’s an incredibly fraught political question—having the ability to take out space debris might also translate into the ability to affect active satellites. And the nations with objects in space aren’t too keen on the idea of a foreign government or company being able to take out, say, a spy satellite along with defunct commercial space junk.

So for now, the government is more focused on preventing new debris from forming than taking the trash out of orbit.

Agencies and companies are likely to continue to develop technology to actively remove debris. But the next steps, Pace said, are likely to focus on “proximity operations” and servicing existing satellites, instead of removing things from orbit. That will include things that can identify tiny satellites and make them more visible.

Of course, this only pertains to American space activities, but the hope is that this will help standardize a set of norms in the nascent commercial spaceflight industry.

“We want this to kind of come from the industry and a dialogue with international partners rather trying to be prescriptive, top down,” Pace said. “What we hope to do is, as those best practices come up, we get guidelines that are non-binding, voluntary, recognized internationally, and then that will be incorporated into national law and regulation.”