While Americans celebrated Black Friday last week, a few lucky Canadians got a rare glimpse of … an incredibly common event. A rocket booster from the recently launched Cygnus spacecraft fell back down to Earth over Saskatchewan, creating a spectacular plume of light in its wake.

Videos of the event spread across the interwebs, and for good reason. Witnessing a re-entry like that is uncommon. But the truth is that debris burns up in our atmosphere once every few days.

Like other seemingly once-in-a-lifetime events—like experiencing a full solar eclipse—bearing witness to a big hunk of metal hurtling towards the ground is only rare because so much of our planet is virtually uninhabited. There are huge swaths covered only by ocean, and enormous areas of land where no (or very few) people live. When you factor in all the communities of people who are unwilling or unable to shoot video on smartphones and beam it up to the cloud (or are simply uninterested in doing so, because we’re not all just doing it for the ‘grams), you’re left with an even greater stretch of the planet where such brilliant displays will go unnoticed by the internet.

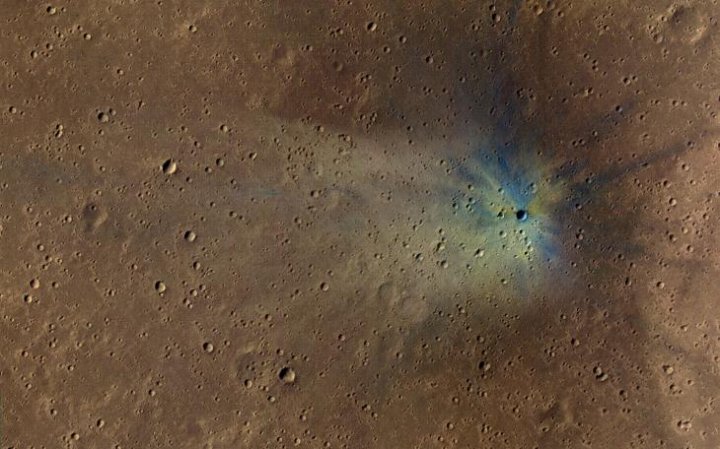

Take last week, for example. Google News was full of articles about the Antares rocket booster that fell on November 25, but had absolutely nothing on a spacecraft that fell the day before. The Iridium 8 satellite went into orbit on May 5, 1997 and crashed back down on November 24, probably somewhere over the Arctic. We have to say “probably,” because no one actually saw that satellite fall. And we’re not great at predicting precisely where and when debris will re-enter the atmosphere, let alone how much of it will beat the heat long enough to actually touch the ground. So like hundreds of pieces of space junk that fall every year, Iridium 8 went unnoticed.

Why is there so much stuff up there, and when will it all come back down?

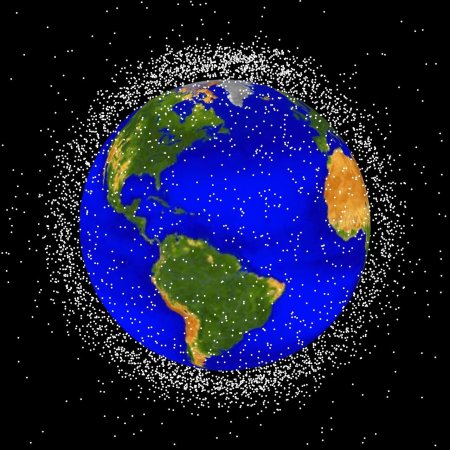

More than 200 objects re-entered the atmosphere in 2016 alone. There were over 600 in 2014, though the average is more like 200-400. No one can really predict how much of our space junk will come hurtling back in any given year, but it’s definitely going to increase unless we do something to prevent it.

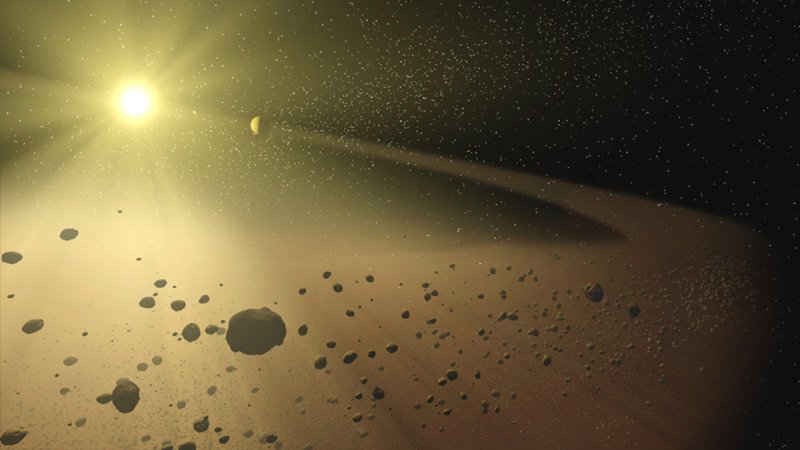

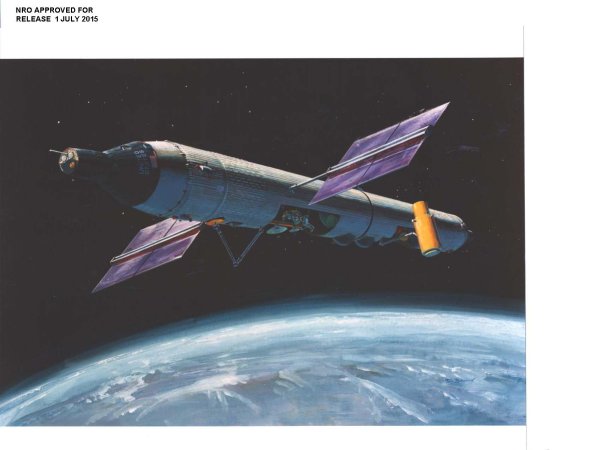

Humankind is putting more and more objects into orbit each year, which means we’re basically creating a cosmic junkyard hundreds of miles above us. If and when those objects collide, they create many smaller bits of debris that continue to circle the globe. And by the way, it doesn’t look nearly as cool as it did in the movie Gravity.

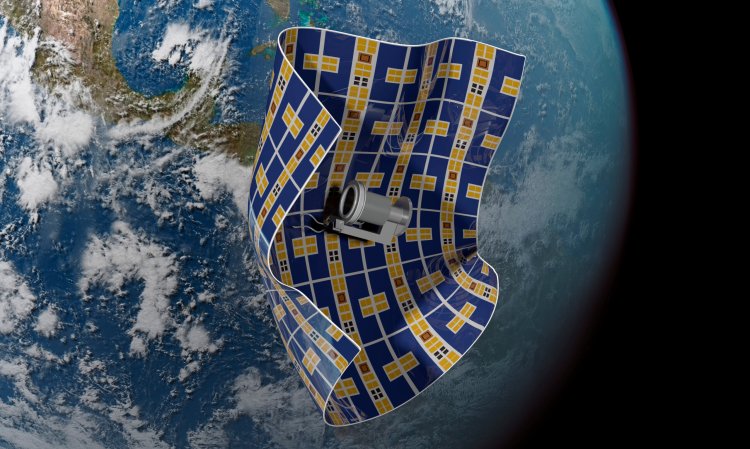

Hollywood likes to slow down the process so you can appreciate all the tiny pieces in motion. In reality, you’d see a flash, and then nothingness. Debris moves at least 17,000 miles per hour, since that’s the speed necessary to maintain a low Earth orbit, and that’s 10 times faster than a bullet. According to The Aerospace Corporation, one of the few organizations that tracks space debris, an on-orbit collision would look “more like an explosion of each object, as if they passed through each other and exploded on the other side.” Orbiting objects are moving faster than shockwaves can go, so when two of them collide they essentially shoot through each other and then feel the impact from the shockwaves. That means after the collision happens, you’d see each piece explode seemingly on its own as the shockwave hits it. But all of that would occur so fast that you wouldn’t even know what had happened. Whatever object you were seeing before would almost seem to disappear.

Because we have so many satellites and old rocket boosters hanging out in orbit, they’re likely to eventually collide with one another and create clouds of debris (on top of the bigger bits) circling our planet. Some of these will fall back down quickly, like the Antares rocket booster, but others descend slowly. Large objects in low Earth orbit can take tens of years to return, and high-altitude satellites take more like hundreds of years, because there’s hardly anything slowing their spin around the globe. But eventually, it all has to come back down.

Isn’t all this falling debris dangerous?

Nah, you’re good.

Aside from the fact that debris mostly falls where no one sees it, there’s just not a lot of stuff that’s big enough to do damage. Most of the objects are small pieces of debris that burn up from the force of hurtling through the atmosphere. Your odds of actually getting hit are about one in a trillion (the odds that you’ll get hit by lightning are one in 1.4 million). Only one person has ever been hit with space trash, as far as we know. Her name was Lottie Williams, and she lived in Tulsa, Oklahoma. A 6-inch-long piece of a rocket hit her on the shoulder on January 22, 1997. She came away from the close encounter without any injuries.

Should I know about any future falling junk that might be cool to see?

What a fortuitous question! In early 2018—sometime between late February and late April—the first Chinese space station will return to Earth. Tiangong-1 launched on September 30, 2011, but it hasn’t been in operation since March 2016. Chinese officials lost contact with the spacecraft, which has been orbiting uncontrolled ever since.

The space station is 34 feet long and 11 feet in diameter. So if you’re lucky enough to see it, this thing could produce a fairly spectacular show. Bits of it will likely break apart, so there could be a little shower of bright objects. Man-made debris tends to stay together longer before it stops glowing, so the streaks from satellites and payloads are often visible for longer than meteors.

Unfortunately, no one knows yet where Tiangong-1 will come down. The trouble with predicting these trajectories is that if you’re off by even a minute, the estimated location will be off by at least 300 miles. We’ll have a better sense in the week or so before re-entry, so you’ll just have to check back for more news later.