Don’t look at the Sun during an eclipse. Wear sunscreen and sunglasses if you go outside. We know plenty about how to protect ourselves from the burning rays of the star we orbit, but what do we really know about how the Sun protects us?

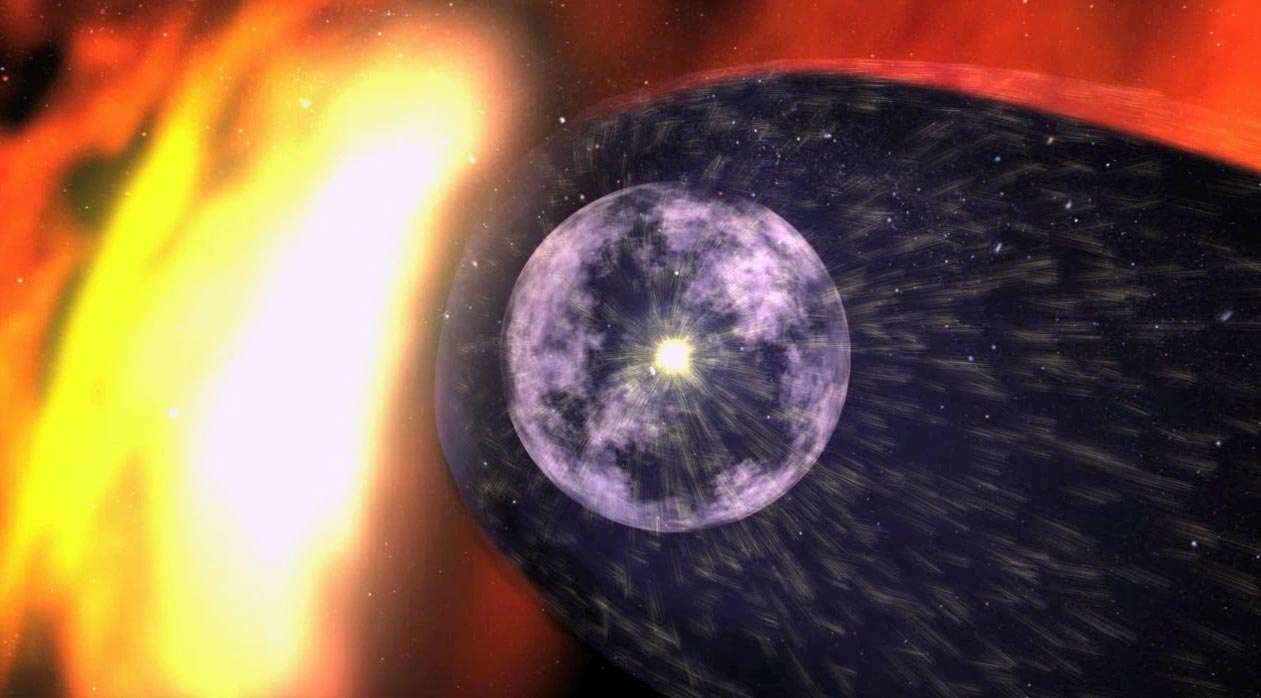

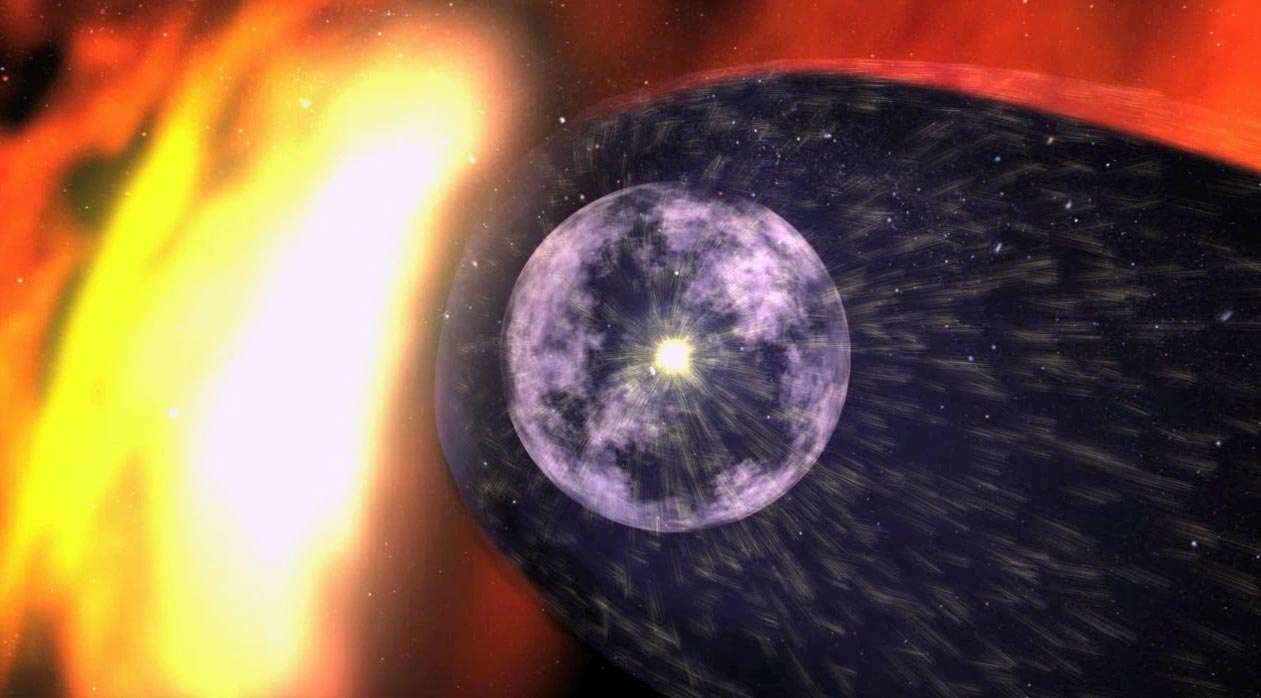

Plasma—ionized gas containing magnetic fields—that streams off the Sun is called the solar wind. When it runs into the magnetic field protecting our planet it can disrupt satellite communication or toy with the electrical grid. But far away from our atmosphere, the solar wind can act more like a shield than a weapon, enfolding our solar system in a bubble that keeps potentially dangerous interstellar radiation away from our tiny planetary community.

Researchers would like to know more about the heliosphere, and now they’re getting a new mission to help gain some insight into this phenomenon. Last week, NASA announced that it would fund the Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe (IMAP) mission, which will send a probe to analyze particles that make it through the heliosphere. The cost of the mission is capped at $492 million, excluding the cost of the launch. For comparison, the New Horizons mission, which flew by Pluto, cost about $700 million.

“This boundary is where our Sun does a great deal to protect us. IMAP is critical to broadening our understanding of how this ‘cosmic filter’ works,” Dennis Andrucyk, deputy associate administrator for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate said in a statement announcing the mission. “The implications of this research could reach well beyond the consideration of Earthly impacts as we look to send humans into deep space.”

There’s just one issue: time. The closest we’ve gotten to the boundary of the heliosphere is with the Voyager missions. Voyager I, launched in 1977, took 35 years to reach this section of the outer solar system. That’s a long time. Researchers, understandably, would rather not wait another several decades to start getting results back from a visit.

Instead, IMAP will have a relatively short journey, heading out to a point one million miles away from Earth—where the gravitational pulls of the Earth and Sun keep spacecraft sent there in a relatively stable position. This spot in space is known as L1, or Lagrange Point 1, and IMAP will orbit this location as it gathers data from the distant solar system.

One million miles might seem like a long way, but it’s only a fraction of the way to the boundaries of the heliosphere. It took another satellite, the Deep Space Climate Observatory, about 117 days to reach orbit around L1 after it launched in 2015. Compared to the 35 years it took Voyager to travel 11 billion miles, it’s just a quick stroll down the block.

Once there, IMAP will use its 10 instruments to collect and monitor particles from outside the solar system. The nature of the heliosphere, including its shape, could help determine how cosmic radiation manages to make it into our solar system. By studying what makes it through, researchers hope they can get a better idea of what that barrier is like. They’re also interested in cosmic radiation for another reason: As humans spend more time in space and send more spacecraft beyond our planet, both the people and tech we send out into the solar system are exposed to increased levels of cosmic radiation. Researchers would like to know more about how this radiation could affect our systems, whether biological or technological.

Still, IMAP won’t launch until at least 2024. While we wait to get a closer look at some of the most distant reaches of the Sun’s effects, we’ll also be taking an exhaustive look at our nearest star with the Parker Solar Probe, which will travel well within Mercury’s orbit—nearer to the sun than we’ve ever been before. That mission is currently set to launch in July.