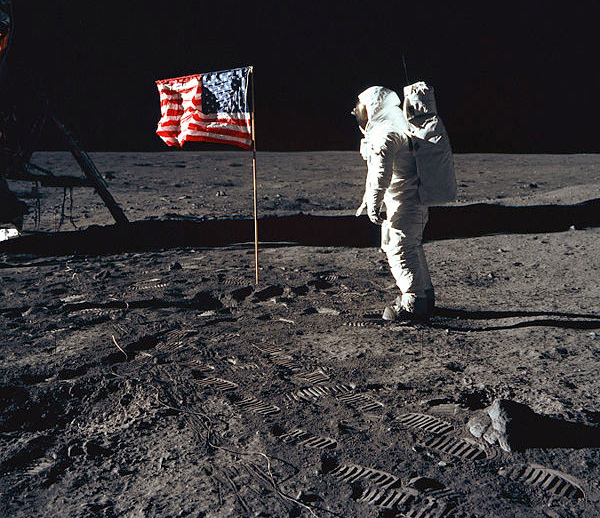

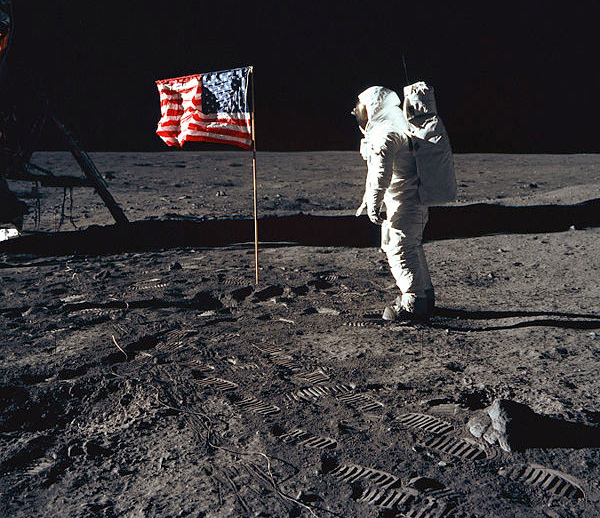

When Neil Armstrong pressed the first bootprint into the Sea of Tranquility, most of humanity watched the televised low-res blob and felt pride welling up in their chests. But a few watchers felt something entirely different—an unconfirmed, squinty-eyed skepticism that something about the whole deal smelled fishy. How could the United States, which could barely put a chimp into space in 1961, get two full-grown men on the surface of the moon eight years later? How could anyone confirm that men actually made it to the moon? And, how, exactly, had that $25 billion Apollo budget been spent?

Five years, and five lunar landings later, the nebulous idea that the government faked the whole moon shot on a soundstage somewhere in the Southwest finally coalesced when, in 1974, Bill Kaysing, a former technical writer for Rocketdyne, a company that worked on the Atlas V launch vehicle, self published a book_ We Never Went to the Moon: America’s $30 Billon Swindle_. Kaysing claimed that the Apollo program was faked to allow the U.S. to secretly militarize space, and that the astronauts, who were put through sessions of “guilt therapy” to help deal with the deception, were actually at a strip club in Nevada the night of the moon landing.

Far from being the work of an exhaustive investigative journalist, its notable lack of evidence, sources, and logical reasoning kept the tome from hitting the bestseller list (or any list). But mistrust of the government—1974 was the height of frustration with Vietnam and the Watergate scandal—gave Kaysing’s semi-formed ideas enough to nudge the Apollo Hoax out of the ether and into the near fringe of pseudo-science. The seed was slow to germinate, but Capricorn 1—a popular 1978 film starring OJ Simpson (who later theorists have implicated in the Apollo coverup) in which the government fakes a manned Mars landing—kept Kaysing’s ideas alive and helped spawn a cottage industry of Moon hoaxers who gathered and presented evidence to one another throughout the 1980s and 1990s.

Despite this, the Apollo Hoax remained fringe, and was on the verge of likely evaporation when the nexus of the Internet and a February 2001 special on the Fox network called Conspiracy Theory: Did We Ever Land on the Moon? put the theory on the public display for the first time. In Fox’s shockumentary era (see When Animals Attack and Temptation Idol), the Moon Hoax documentary and a replay a month later were ratings successes, and became water cooler fodder across the country with people asking “why weren’t there stars in the photos?” And “How could the astronauts have survived the radiation of the Van Allen Belts?” Aided with a blossoming of Internet conspiracy sites, the Apollo Hoax made its first true toehold in the mainstream press.

Join PopSci as we celebrate NASA’s 50th anniversary!

At the same time Fox was giving credence to Kaysing’s ideas, astronomer Phil Plait was preparing the defense. On his Web site Bad Astronomy and in a later book of the same name, the professional astronomer refuted the claims of the Fox show and Kaysing (who passed away in 2005) point by point. Plait’s refutations spawned dozens of other debunking sites, setting off a veritable Internet war between hoax believers and their critics. There have been a few notable events since then—in 2002, Bart Sibrel, who appeared in the Fox special, was punched in the face by astronaut Buzz Aldrin after poking Aldrin with a Bible, asking him to swear to the moon landings authenticity. More recently, Fear Factor host Joe Rogan has gone to bat for the Moon Hoax Theory, debating Plait on Penn Jillette’s radio show. But as for hard evidence? The stories haven’t changed much since 1974.

“In ten years I think this conspiracy theory will be gone,” says Plait, who points out that in 2009 NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter will give us clear photos of the moon landing sites, and says the U.S. goal of returning to the moon by 2020 will refocus us on the triumph of the Apollo mission. “These guys are not professional journalists, they have no credentials, and their arguments are tissue thin. They have a track record of 100 percent errors.”

Though the hoaxers claims usually disappear when held up to the light, there is one question that sticks in one’s craw: what happened to the official videotapes of the Apollo 11 landing? To save space in the broadcast spectrum so they could transmit telemetry and other data, cameras on the lunar lander transmitted images in a special slow-scan format. That data was received by stations in Australia and the Mojave, formatted for television broadcast and sent to Houston. The images seen on television were fuzzy and indistinct. The actual slow-scan footage before conversion was crisp and full of detail.

But those priceless historical images weren’t put in a vault at the Smithsonian like they should have been. According to NASA records, the official video images of the moon landing were stored in 2,612 boxes at a government warehouse. Between 1975 and 1979, the Goddard Space Center requested all but two boxes of tapes and never returned them to the National Archives. Now, the 13,000 reels of data are nowhere to be found. In 2006, NASA began a dedicated agency-wide hunt, but to date, the images haven’t shown up. “Despite the challenges of the search,” a NASA release states, “NASA does not consider the tapes to be lost.” But the hoaxers and moon doubters do. And it’s unlikely their questions will be put to rest till we put another footprint on the moon.

View the scant remnants here.

Join PopSci as we celebrate NASA’s 50th anniversary!