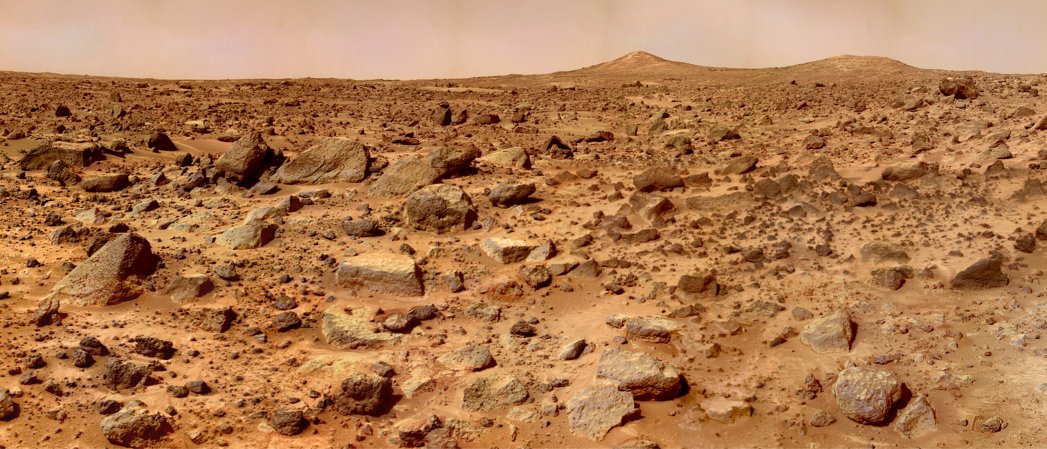

We may like to think of ourselves as independent agents, but our reliance on microbes to digest our food and fight off diseases makes us far from isolated. Foreign germs actually outnumber more familiar bits of our bodies like skin cells and neurons. So if astronauts ever visit Mars, we know they won’t go alone—and they’ll spew countless microbes into the alien environment as they eat, shower, and relieve themselves for however long they stay.

Scientists aren’t sure how these critters will fare on the Red Planet, however, and an essay published recently in Microbial Ecology says that’s a big problem. Most talk of microbes in space has previously focused on how we might avoid littering alien worlds with our stowaway species, but the authors of this new paper argue that contamination is inevitable. Instead of speculating on how to minimize an astronaut’s microbial footprint, they say, the space community will eventually need to focus on harnessing the critters to work for us.

“We could use the microbes, which have been around for billions of years, to help us in these future endeavors,” says Jose Lopez, a biologist at Nova Southeastern University in Florida and one of the essay’s co-authors. “Humans are just a blip on the evolutionary timescale. It’s the microbes that can tell us how to survive.”

The provocative proposal highlights the conflict between those who would have humans call Mars home and those who would keep it a pristine astrobiology laboratory.

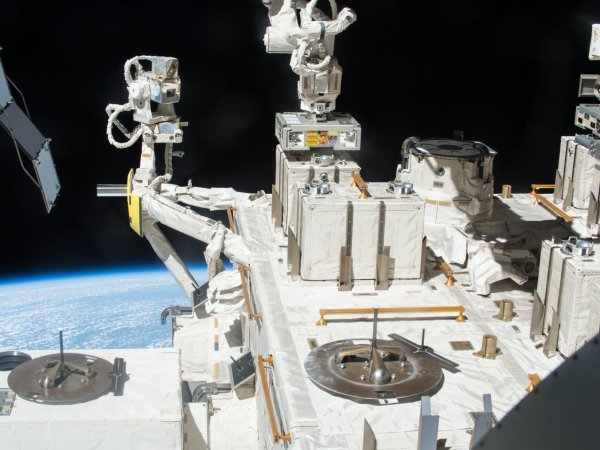

Historically, space agencies have viewed microbes as enemies. More than 100 countries (including the major spacefaring nations) have voluntarily agreed to follow the recommendations of the Committee on Space Research (COSPAR), an international organization for interpreting the Outer Space Treaty—the closest thing to international space law. One recommendation is that states (and companies launching missions inside those states) keep their spacecraft clean enough to avoid “harmful contamination of space and celestial bodies.”

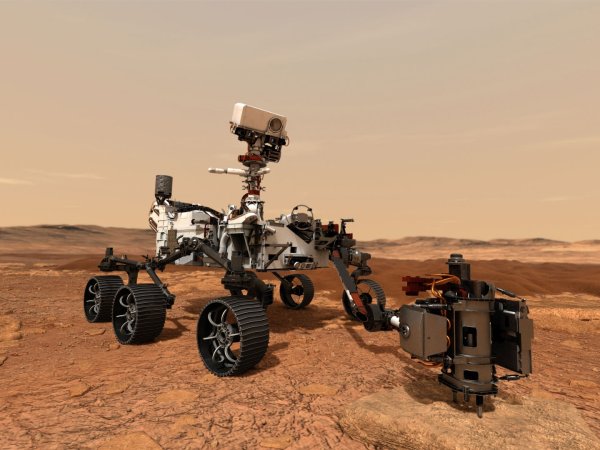

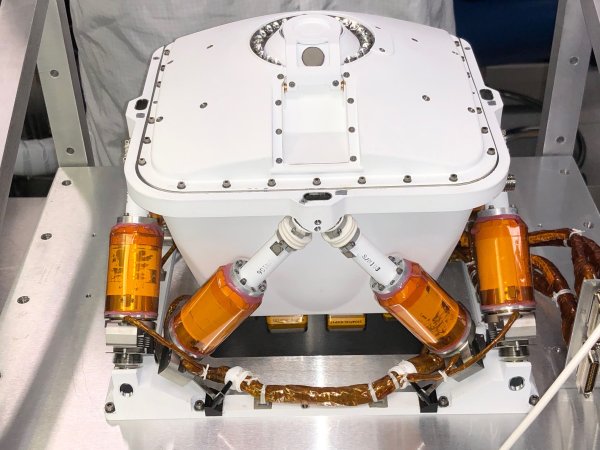

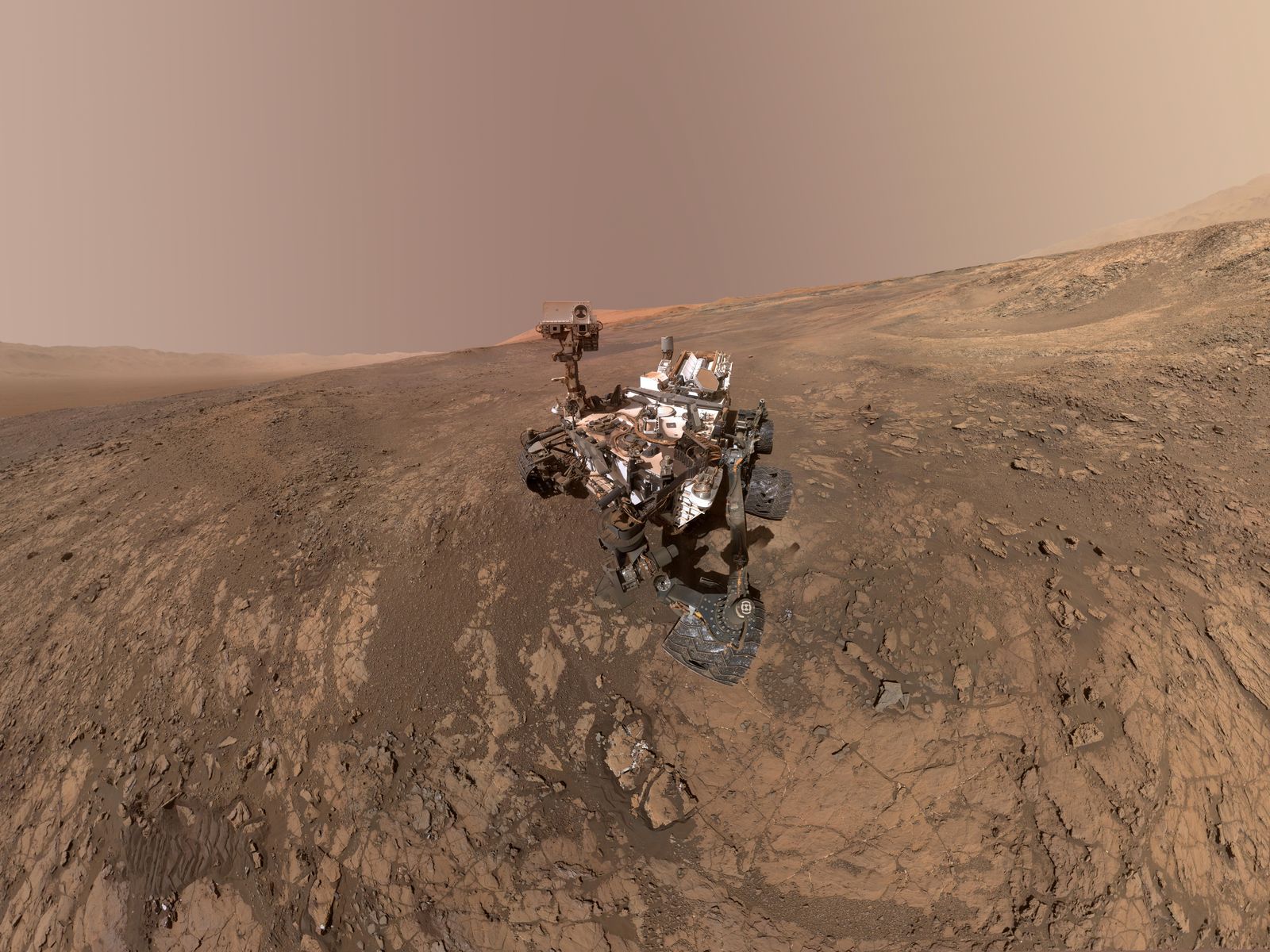

To comply, space agencies have implemented so-called planetary protection guidelines that vary depending on a mission’s destination and goal. NASA, for instance, ensures that no more than 300,000 bacterial spores make the trek to Mars on a rover’s external surfaces. These cleanliness measures can inflate a mission’s budget by as much as 10 percent, and sometimes complicate its design. Engineers had to build the landers of the 1970s Viking mission—NASA’s only attempt to directly detect Martian life to date—to survive four days of sterilization in a 200-degree oven.

But the moment humans land on Mars, Lopez and his colleagues contend, the anti-germ battle will be lost. As walking skin-sacs stuffed and overflowing with microscopic bugs, we will spread life wherever we step. So before we go offering free rides to countless known and unknown organisms, Lopez proposes, we ought to thoroughly vet our travel companions, studying who they are, how they’ll survive, and whether they’ll make good roommates.

“Symbiosis research is relatively underappreciated,” he says. “More research is needed here [on Earth] in the context of survival and potential colonization of planets in the solar system, because [microbes] are going to be required.”

Lopez envisions a multi-decade research program dedicated to figuring out how to reject dangerous microbes and welcome friendly ones. Going even further, he speculates about selecting the hardiest of Earth’s microbes and engineering them to do useful tasks on Mars, such as creating oxygen for domed habitats. He praises COSPAR’s planetary protection work to date, but says that such stringent scientific requirements would someday conflict with attempts to live on Mars. “We might have to choose,” he says.

Some researchers applaud the essay’s message. Alberto Fairén, an astrobiologist at Cornell University, has long called for less stringent treatment of spacecraft and looks forward to possible updates from NASA’s new planetary protection officer. “Up until one year ago or so the protocols were just asphyxiating,” he says, “but the tide is changing now at a very interesting pace.”

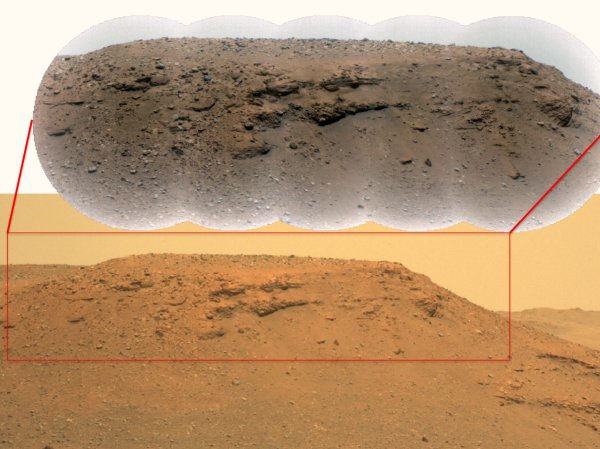

Other scientists, however, lament that prioritizing settlements and deliberately introducing microbes willy nilly could damage, or end, the hunt for indigenous life on Mars. Viking’s life detection experiments came out inconclusive because researchers didn’t know enough about the Martian environment to fully interpret them, says John Rummel, an ex-planetary protection officer for NASA. Today’s rovers are figuring out exactly how local rocks and chemicals act so that some future robot will have a better shot at finding Martians. If that future rover finds an exotic microbe in an area where some astronaut once planted a Matt-Damon-inspired potato garden, certifying that critter as a native Martian will be a lot harder.

Rummel sees planetary protection as an important first step toward living on Mars, not necessarily an obstacle to it. Before future farmers enrich the soil for potato farming, they’d want to know how the soil might react. Waking up dormant local bugs that produce toxic gases, for instance, would come as an unwelcome surprise. “If you want to push the Martian environment using microbes etc.,” Rummel says, “are there Martian microbes there that will push back?”

Yet researchers have plenty of ideas for how they might have their hunt for life and live there too, and they’re not so different from how we balance the economic rewards of industry with the health risks of air and water contamination here on Earth. In short, we’re going to need some zoning laws.

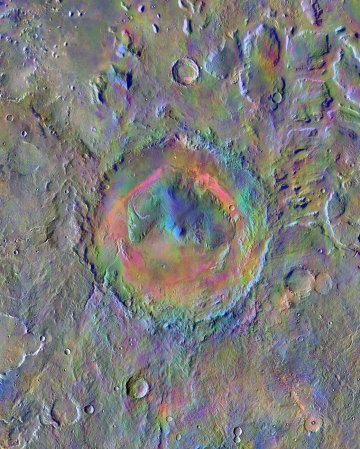

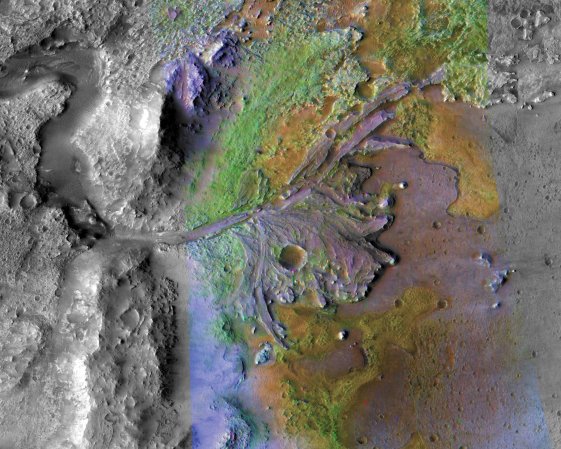

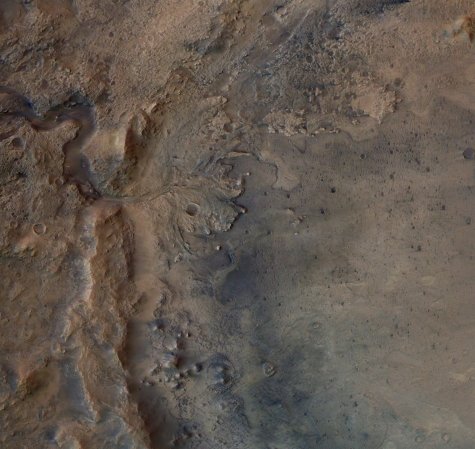

COSPAR and NASA continue to discuss what might constitute a “special region” on Mars—places not too hot or dry for life as we know it. These areas could become the first Martian science preserves, home only to sterilized rovers. Rummel imagines a planet-wide wind and dust monitoring network that makes sure special regions stay special. “It’s a big planet,” he says, “and not everything has to be done the same way in all places.”

Margaret Race, a biologist at the SETI institute specializing in planetary protection, says that essays like Lopez’s are an essential step toward balancing the desires to use Mars as well as explore it. She points out that just as the Wright brothers couldn’t have foreseen the need to stow tray tables before landing, COSPAR’s current planetary protection guidelines are just the opening statements in a long conversation. While some see the 2030’s (when NASA and other organizations hope to land boots on the Martian ground) as a pressing deadline, Race says that the kind of settlement needed to seriously contaminate large areas of Mars remains more than a human lifetime away.

In fact, she says, humanity has already successfully found compromises while studying another science preserve: Antarctica. When Russian researchers attempted to drill deep through the ice into the buried Lake Vostok to search for (comparatively) alien microbes in the 2000s, other researchers raised concerns that the dirty drill bit would contaminate the pristine lake, which had remained isolated for millions of years. Working within the framework of the Antarctic Treaty, which the Outer Space Treaty is based on, the Russians paused to consider environmental effects. After determining that the pressurized lake water would squirt out of any breach in its icy encasement, they landed on a strategy of poking a small hole (with a cleaner drill bit) and analyzing what came out, without any need for direct contact with the lake.

When they announced the discovery of a new bacterium, the possibility of sample contamination made the result controversial. But the lake’s integrity is at least preserved for future research. On Mars too, perhaps future explorers and researchers will find strategies that can keep the peace. “If you stop and think ahead,” Race says, “maybe you can’t do everything you want, but it doesn’t mean you stop.”