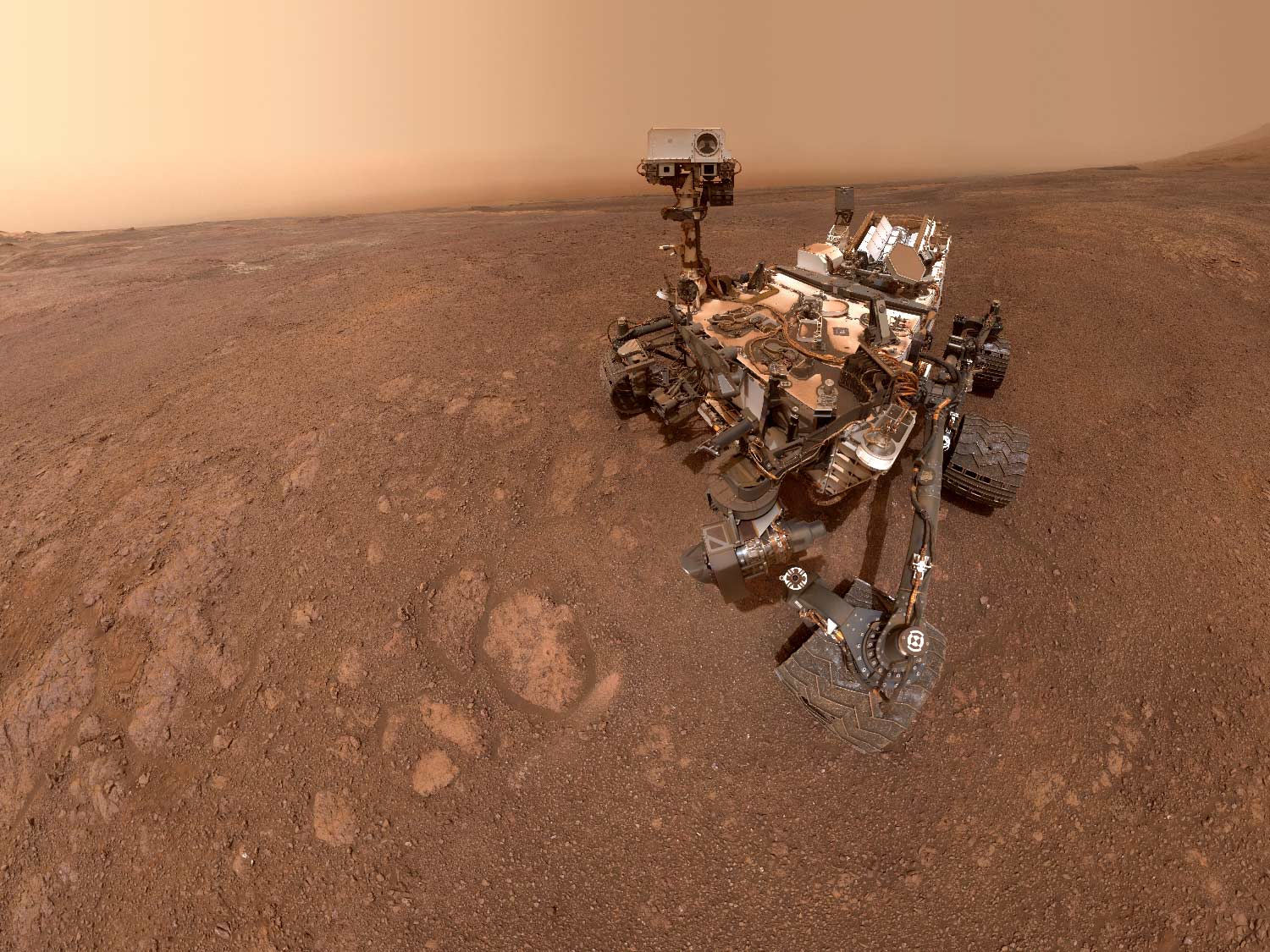

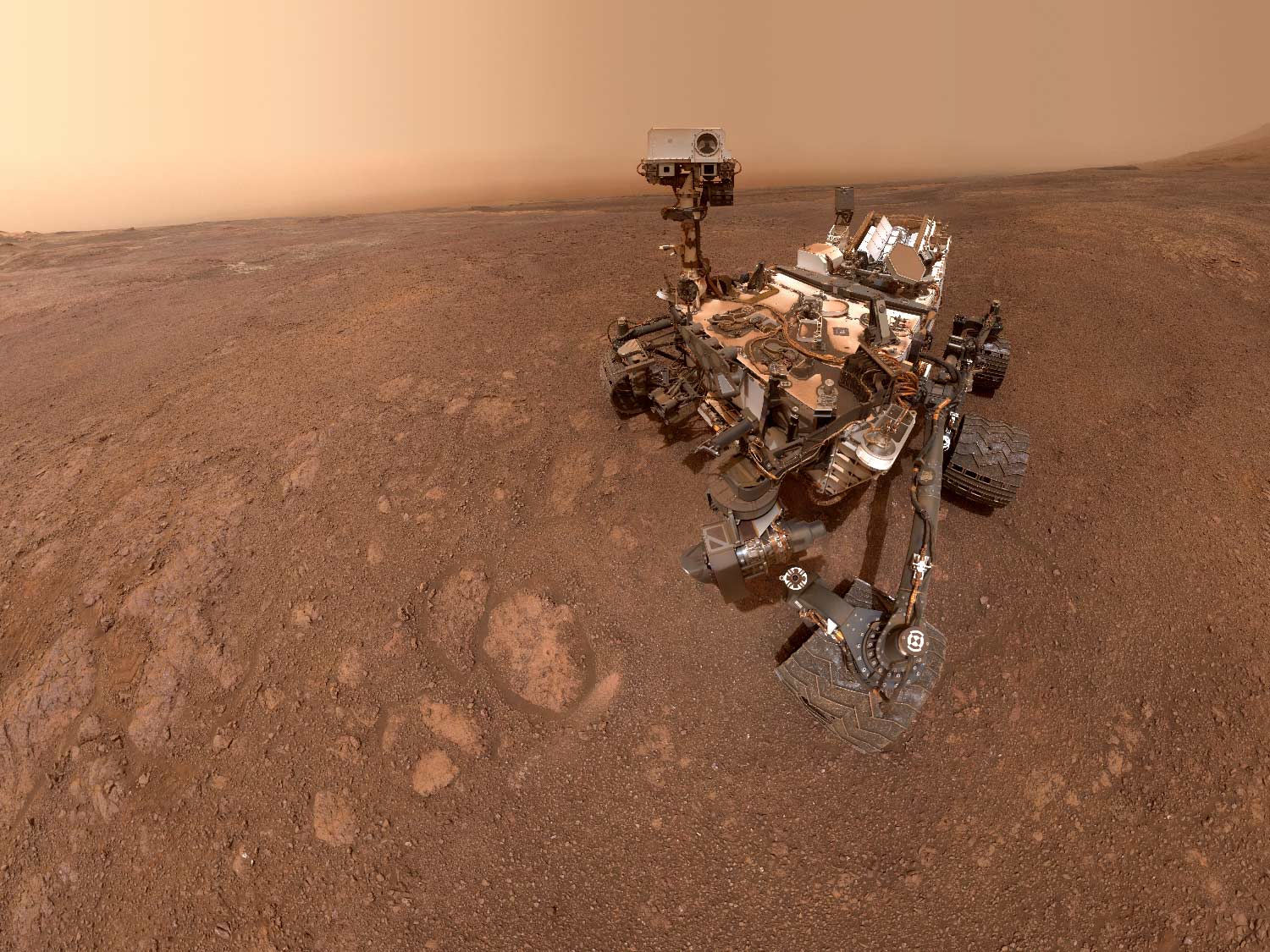

Methane is back in the news, but this time not in the dreadful harbinger-of-climate-doom kind of way. The New York Times reported over the weekend that NASA’s Curiosity rover had stumbled upon surprisingly high methane levels in the Martian atmosphere near the Gale Crater—at least three times higher than Curiosity measured in 2013. The announcement, confirmed by NASA, once again stokes hopes that we’ve picked up signs of extraterrestrial life on the red planet.

“It’s always interesting to see new data like this come in, because it gives us something more to think about and assess and analyze,” says Dorothy Oehler, a Houston-based planetary geologist and senior scientist for the Planetary Science Institute. The big question on everyone’s mind is whether there’s something we can glean from this peak that explains the origins of Martian methane better than previous investigations. “It’s obviously a pulse of energy and interest. And we’re working to see how real this is.”

But that’s just it—the question of how real this methane spike is, and what it means for the search for life on Mars, is unanswered and complex. More likely than not, this latest observation will only inch us closer to answers, instead of handing them over outright.

Finding methane on another world is a big deal because it’s a gas some microbes on Earth produce. These organisms, methanogens, survive in conditions with very low or no available oxygen, and release methane as a waste product. They’re often found in wetlands, rocks residing deep underground, and even in the digestive tracts of some mammals. Yup, they’re why cow farts and burps are ruining the world.

Bovine flatulence notwithstanding, it’s not hard to see how something like these organisms might have evolved when Mars was warmer and wetter—and how they might even have found a way to survive underground as the red planet became a cold wasteland. Methane breaks down in just a few hundred years once it’s exposed to the atmosphere, so gas at levels detected on Mars must have been released recently.

We’ve detected these spikes before, but those repeated measurements haven’t produced much clarity. The Curiosity rover possesses an incredible onboard suite of scientific instruments, but it’s not optimized to measure these gases or run the sort of assays that could give us a hint of their origin. Oehler previously worked on an independent confirmation of Curiosity’s 2013 methane detection, made possible through observations from the European Space Agency’s Mars Express orbiter. It was encouraging evidence that these peaks were real.

And yet the ESA-Roscosmos ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter—explicitly designed to look more sensitively for levels of methane in the Martian atmosphere down to parts per trillion—found nothing in its first batch of results. We’re certainly finding methane on Mars, but we’re not really any closer to understanding what that means.

The transient nature of these spikes only exacerbates the confusion. NASA confirmed Monday that Curiosity’s read on the methane spike, which peaked at 21 parts per billion, had dwindled back down to background levels below 1 part per billion. “That’s been our experience with methane peaks on Mars,” she says. “They don’t last very long,” vanishing after just one or two Martian days. And even 21 parts per billion is still two orders of magnitude lower than what we see here on Earth.

Perhaps none of Mars’s methane is actually fresh. Methane can get trapped in permafrost and ice on Earth, and Mars has plenty of ice old enough to contain methane produced billions of years ago. “All you have to do,” says Oehler, “is stress the planet or change local conditions in some way that could destabilize the ice” and release the gas out to the surface. These rumbles could be caused by seismic activity, latent volcanic activity, meteor impacts—anything that can open up faults and breach the permafrost seal. Håkan Svedhem, project scientist for the TGO mission at ESA, also adds that shifts in temperatures triggered by seasonal or diurnal effects could open up a path for discrete concentrations of gas to move to the surface.

And although methane is a strong sign of biological activity, it’s far from a definite indicator of past or present alien life. Oehler thinks it’s likely at least some of the gas came from geophysical processes. The most common abiotic generators of methane on Earth are Fischer–Tropsch reactions, where an oxidized form of carbon combines with hydrogen to produce methane and water. These are typically high-temperature reactions, but there are some versions of the phenomenon that can occur in Mars-like climates.

A second source of abiotic methane is thermogenesis—the heating up of buried organic matter. “That happens on Earth all the time. In fact, that’s how we get oil and gas from organic matter,” says Oehler. Meteorites could have delivered that organic matter to Mars. Impact heating could have broken it down into methane, and freezing conditions could have siphoned it into ice trappings underground.

The first major step is to figure out where the methane is coming from. It’s likely a subsurface source, but even that’s unconfirmed. Svedham points out that both TGO and Mars Express happened to collect observations remarkably close to the Gale Crater at the same time as Curiosity. That triumvirate of data, in conjunction with measurements in temperature and atmospheric winds, could give us a narrow target to explore.

This Martian methane mystery probably won’t be solved without some ground-based investigations on the surface and subsurface. “We have to consider the possibility that there are some processes on the planet that are poorly understood—some methods or mechanisms of rapid destruction or sequestering of methane that’s not measured in the atmosphere,” says Oehler. Some others might suggest our best bet for that sort of study is the Mars 2020 rover, which will be able to drill two meters into the ground. It doesn’t sound like a major feat, but it might be just enough to shine some light on what—or who—is passing all this gas.