SCHIAPARELLI WAS OUT OF CONTROL. As the probe entered Mars’ atmosphere on October 19, 2016, an onboard computer miscalculated its altitude, prematurely jettisoning the craft’s parachute. The disc-shaped probe with what looked like a futuristic World’s Fair of instruments on its flat back sent one last swan song of a data package back to its circling companion, the Trace Gas Orbiter, as it tumbled into free fall. Onboard thrusters fired for three seconds rather than 30. Then, some 1,272 pounds of atmospheric and meteorological sensors—and nearly two decades of European deep space ambition—slammed into Mars at 335 mph. The probe added another crater to the pockmarked surface, peppered a stretch of the Red Planet with mechanical debris, and joined a growing list of disappointments in the European Space Agency’s quest to make its first successful landing on Martian soil.

Part of the first mission of the ExoMars program (a reference to exobiology, the study of life beyond Earth), the Trace Gas Orbiter still circles the Red Planet today, high above its failed entry module. But the program is defined by continued setbacks. Since the project’s inception in 2001, it’s been plagued by bureaucratic delays, budget shortfalls, geopolitical turmoil, and mechanical failures. But ExoMars received its fiercest blow in more than two decades when Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022. The ongoing war has left the future of ESA’s next attempt—which was meant to touch down on Mars in June 2023—up in the air.

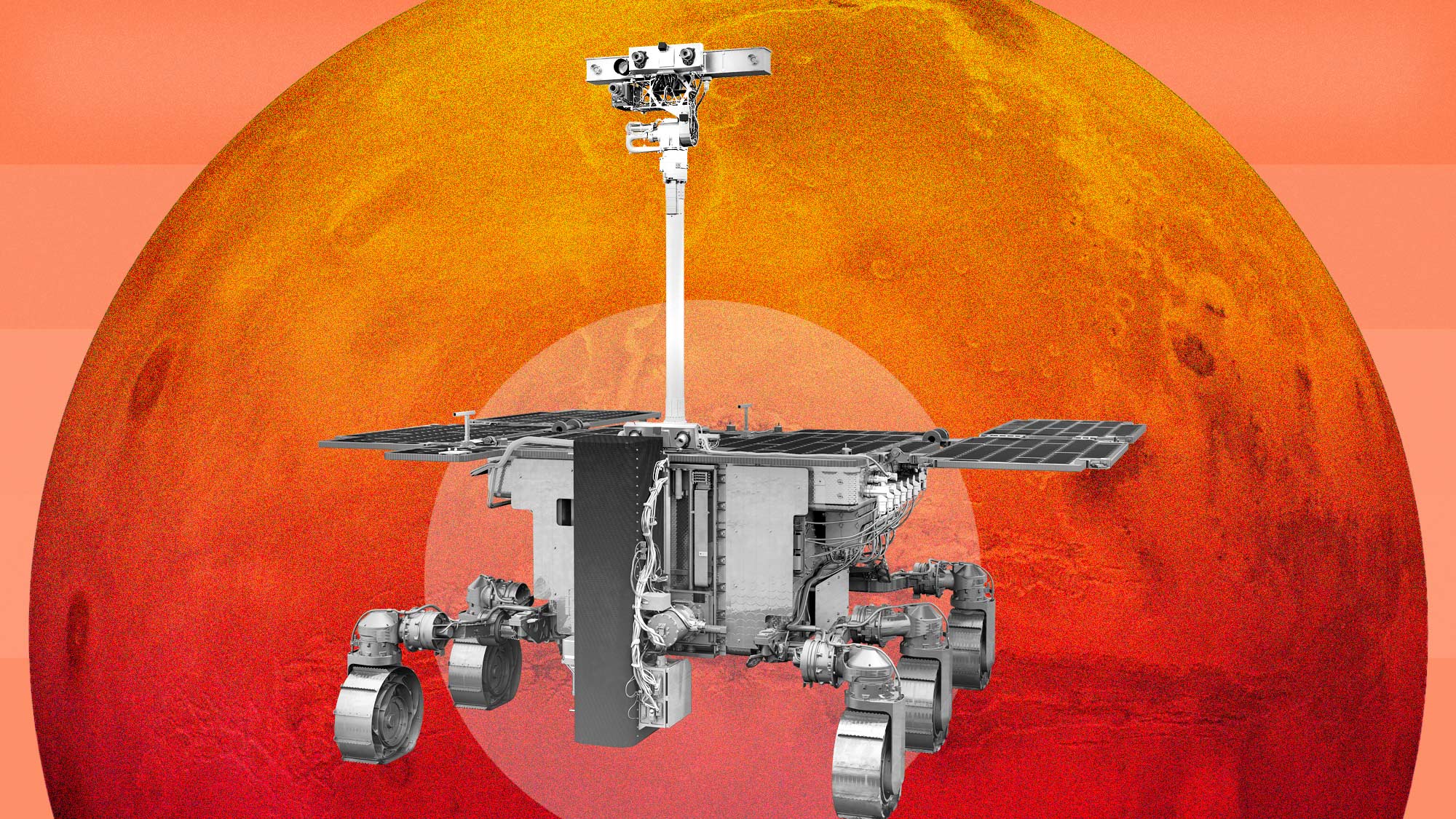

Despite the resilience of the engineering teams and scientists behind the mission, their efforts increasingly seem more Sisyphean than Herculean. As the rover sits motionless in a facility in northern Italy, its precious components—some made of rare-earth minerals and gold—are at risk of atrophy and decay. Funding is in limbo until the US Congress and European member states decide whether to invest more cash.

If the rover launches in 2028, as is currently planned, it will represent the culmination of roughly 30 years of patience, redevelopment, and, most recently, a European reunion of sorts for NASA. This follows a long line of setbacks and disappointments that began long before Russia’s war in Ukraine booted Russian space agency Roscosmos and its booster engines from the program.

Getting Rosalind Franklin (named in honor of the late English chemist known for her contributions in identifying DNA’s double helix) to a safe landing spot millions of miles away will require unfettered determination and a level of global cooperation that seems increasingly difficult to maintain. If they want a chance of making it to the finish line, the mission’s leaders will have to let go of some of their original goals.

As Jorge Vago, an ExoMars project scientist, puts it: “It’s now about surviving.”

MARS HAS BEEN a primary target of international space exploration since NASA launched Mariner 4 in 1964. This fly-by mission supercharged modern humanity’s fascination with the Red Planet, which has inspired a relentless, decades-long quest to uncover its secrets. Central to this exploration is the search for extraterrestrial life, a pursuit that has spawned numerous rover projects and brought together leading global space agencies.

The modern era of Mars exploration started when NASA’s Pathfinder arrived on the Martian surface in 1997. Among its discoveries were confirmation about ancient water and new information about the planet’s thin atmosphere, fueling the scientific community’s interest in Earth’s neighbor as a potential human habitat. That focus brought us the Mars Science Laboratory, launched in 2011 to deliver NASA’s car-size Curiosity. Equipped with a state-of-the-art scientific payload, it discovered organic molecules and complex chemistry in the Red Planet’s soil, strengthening the case for past or even present microbial life. Through these discoveries, NASA remained close partners with ESA, which launched its Mars Express orbiter on a Russian Soyuz in 2003. In 2009, NASA and ESA made joint commitments to two more Mars missions. Meanwhile, ESA’s ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter, launched in 2016 in collaboration with Russia’s Roscosmos, is still analyzing the Martian atmosphere for gases associated with biological or geological activity.

Astronomers now know that Mars once hosted a climate that could sustain life, before a dramatic shift made the dusty planet as hostile as it is today. Uncovering what happened millions of years ago could help improve our understanding of how and when life tends to evolve in our galaxy. It could also provide hints about the trajectory of Earth’s own changing climate.

Projects in the heavens also serve as tools for diplomacy, fostering international cooperation and shared scientific goals to better the planet. ExoMars was meant to be one such collaboration, but NASA couldn’t sustain its financial partnership and departed the program in 2012. Roscosmos partnered with ESA in NASA’s stead, securing the future of the mission.

Then everything came undone.

After Russian troops and weapons entered Ukraine in February 2022 in an unprovoked assault on the eastern European nation, ESA canceled its contract with Roscosmos in line with Western sanctions. The program already had its rover, but nothing to deliver it to Mars. ESA scrubbed the September 2022 launch date.

Russian scientists spent that April dismantling their equipment from the lander, while engineers at ESA facilities across Europe worked to reimagine how they might adopt outside equipment into their designs. One example is the lightweight radioisotope heater units that would save energy and keep the rover from freezing during Martian winters. Those heaters are produced only by Russia and the US, but a swap will not be seamless: The Russian versions were each about the size of a mini soda can, and the Rosalind Franklin rover was designed to accommodate three. The American substitutes are more like 35mm film canisters, and it will take at least 30 to keep the rover warm. Attaching them will require some nimble tinkering.

Now NASA is poised to give ESA the boost it needs to vault over the mission’s final hurdles. If the agencies are able to retrofit lander parts for instruments customized for Roscosmos tech (also not a small feat), the rover could be launched from Kennedy Space Center on a US-owned rocket. But the success of the salvaged mission hinges on more than just engineering.

“It’s a Russian nesting doll in that sense, the way we built up the partnership,” says Albert Haldemann, Mars chief engineer at ESA. Now the two space agencies have to assemble the parts and make sure they fit well enough to survive the journey to Mars—and its volatile atmosphere.

SINCE 2022, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has killed tens of thousands of people, displaced millions more, exacerbated political tensions around the globe, and cast a shadow over future collaborations in space exploration, including the International Space Station. Vago recalls having difficulty processing the news. “We were devastated…wrenched,” he says.

The team was tormented by two realities following the loss of Russia’s space instruments and expertise: the potential collapse of ExoMars and a void in the world’s astronomical knowledge. A morose fog fell over the mission.

“The realization of what was happening hit different people in different ways at different times,” Vago says. For a brief period, it wasn’t clear how they would or should proceed. “If it was someone else’s mission, looking with some detachment, you’d say, ‘Yes, of course you can’t launch with this war going on and with cooperation with the side that started it,’” he explains. “The other half of your brain is thinking, I’ve been working on this thing with colleagues from the US, Russia, Europe, and they are nice and sweet. That’s 20 years down the toilet.”

The abrupt end of the partnership severed emotional ties too, says Haldemann. “There are personal stories on both sides.” The main Russian partner was NPO Lavochkin, a military supplier to the Russian army. “I suspect some of the people I worked with are full supporters [of the invasion], and that feels a little weird,” Haldemann adds.

When Russian cooperation collapsed, the European team moved back to one of the very first phases of development for the lander, essentially backtracking from final flight checks to the process of creating basic equipment. NASA saw an opportunity to rejoin another mission with a longstanding ally, which will mean a surprise comeback if it moves to officially support the project again. ESA is now cobbling together a new game plan that accounts for the loss of resources—and includes replacements it hopes it can count on. The new launch date is tentatively set for 2028; the six-year delay represents the bare-minimum time the team will need to design and build and test new equipment.

“The uncertainties now are more on whether we will get the US contributions in time to match with the plans that we have at the moment,” Vago says.

Plenty of US players are eager to see a successful continued collaboration on Mars. The reengagement with overseas partners after years of “America First” diplomacy was a long time coming, says Charles Bolden, who served as the NASA administrator from 2009 to 2017. Despite the uncertainties surrounding the ExoMars project, its original intent to promote international cooperation through scientific exploration remains an inspiring one. As the world grapples with the challenges of the present, the quest to uncover the secrets of Mars and the potential for life beyond Earth serves as a powerful reminder of what humanity can achieve when working together toward a common goal.

“It’s a golden opportunity for us to work with the Europeans in this project,” Bolden says.

In a way, the mission replicates the tensions surrounding the future of global space exploration and cooperation.

This March, the White House proposed $27.2 billion for NASA’s 2024 budget, with almost $950 million supporting the agency’s ongoing collaboration with ESA to bring samples from the previously launched Mars 2020 project back to Earth. The desired budget also allocated an unspecified amount “toward US collaboration with the European Space Agency’s ExoMars rover mission.”

The Presidential Office Budget still needs to wend its way through a Congressional process of budgetary drafting, amendment, and approval. So for now the wait continues. “We’re encouraged by what we’ve seen [from the US], so hopefully we’ll see a commensurate amount of funds,” says Eric Ianson, Mars Exploration Program director at NASA. “We’re operating under the assumption right now that we will get the funding, so we’re continuing.”

But while that may be enough to save the mission, it won’t be enough to save every part of the nesting doll. “If anything, we’re cutting,” says Vago of the mission’s scientific instruments. “We are [now] interested in keeping things as simple as possible. We’re getting rid of anything that is not essential for the landing and for helping to deliver the rover to Mars.” With a drill capable of digging to depths of up to two meters, however, Rosalind Franklin’s main objective of subsurface sample extraction and analysis remains unchanged. She will plumb the Martian soil farther than any of her predecessors—anything else will be a bonus.

With ESA workers investing time and brainpower into facilitating the use of American equipment, each month without a US commitment intensifies the palpable anxiety of the team. In a way, the mission replicates the tensions surrounding the future of global space exploration and cooperation.

On a recent afternoon in March, a reminder of the dissolved partnerships sat at an unassuming gated factory on a windy industrial stretch south of the Alps in Turin, Italy. Inside lies a modified clean room where a mission control station overlooks a mock Martian landscape. The Russian landing platform sits abandoned in a corner. Once meant to provide its own package of instruments to monitor an alien environment, the glorified ramp now collects dust.

Rosalind Franklin is stowed a few buildings away, in an over-pressurized room at the Thales Alenia Space facility. Along with her earthbound training twin Amalia, she’s undergoing regular maintenance and continued testing to stay prepared for a launch that should have happened last year. The hopes and setbacks for the mission are on display as scientists and engineers continue exercising the rover and its operators in the hopes of maintaining mission readiness. Meanwhile, they scramble to source batteries, plutonium, and booster engines that were meant to come from Russian collaborators.

The mission’s chances will now be determined by NASA, which has both the engines and the plutonium necessary for the launch. So the ESA team’s work is never done—a nesting doll of collaborations that must be revisited, maintained, and renewed.

“I’m reinvigorated by the fact that [EU] members have committed money on the table to see that the rover happens,” says Haldemann. He notes that for some, the mission has made up the bulk of their careers. Russia’s war in Ukraine shattered some of those dreams. “It’s bittersweet. It’s an emotional roller coaster for a lot of members of the team who were on the verge of launch.”

“It bothers everyone that the war happened,” Vago adds. “If I look at it in terms of the mission…the war has affected so many people, but it has also affected our colleagues who were working on these teams from the Russian and Ukrainian side.”

Until NASA officially commits to the mission, the ExoMars team has to muscle its way forward, as it has for many years. “If we had been able to pluck a ready-made lander off the shelf, we could have launched in 2024,” Vago says. “But no such luck.” In times of war, it’s important to be resourceful, pick the right allies, and survive.

Kenneth R. Rosen is an independent journalist based in Italy and the author of “Troubled: The Failed Promise of America’s Behavioral Treatment Programs.”

Read more PopSci+ stories.