“A coral reef is very busy and very noisy. There’s lots of clicking sounds, there are fish grunting,” says Suzanne Mills, an endocrinologist with EPHE PSL Research University and the Center for Insular Research and Environmental Observatory (CRIOBE) in Moorea, French Polynesia. That cacophony comes from big guys picking on small fries, think again. “We have video footage of an anemonefish biting the tale of a shark—and the shark flinching.”

Anemonefish often have orange and white stripes with black accents that give them a distinct harlequin appearance, hence their nickname—clown fish. Visually, they’re best known as Nemo from that Disney movie you’ve seen way too many times, although sometimes they come in other color combinations. And as Mills illustrated, they are tough little fish. The problem, according to a recently released study in the journal Nature Communications, is that climate change might be even tougher.

The issue is that anemonefish, as their name might suggest, depend on sea anemones for their survival. Sea anemones are brightly colored animals closely related to coral and jellyfish. Like jellyfish, anemones sting. And like coral, they spend most of their lives fixed in place—either attached to rocks on the sea bottom or on reefs—where they wait for fish to swim by and get caught in their venomous tentacles. It is, as they say, a living.

But while sea anemones generally eat fish, they don’t eat anemonefish. The clever clowns coat their bodies in a mucus that stops anemones from recognizing them as dinner. As a result, anemonefish use anemones as shelter, where they hide from predators who are more prone to a venomous attack. In exchange, the fish scares away anemone predators like the butterfly fish and turtles (they go for the eyes).

Turtles aren’t a sea anemone’s only nemesis, however. Warming waters, increasingly common because of climate change, can cause sea anemones to bleach just like coral reefs. Instead of keeping their vibrant hues of pink, purple or even brown, the anemones, like coral, lose key symbiotic algae as water gets too warm. Beyond giving an anemone its flashy coloration, the algae supplies the creature with oxygen and food. In exchange, the algae gets carbon dioxide and a place to call home. This relationship breaks down as temperatures increase, leading the anemone to turn white as the algae depart. But what happens to anemonefish when their buddies get bleached?

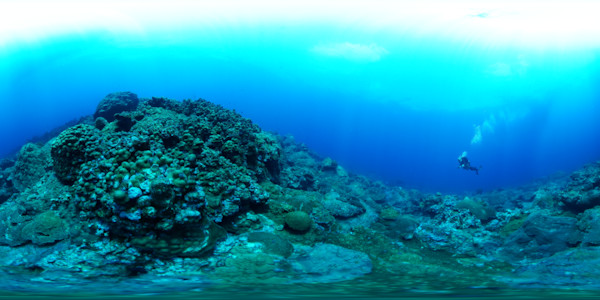

To find out, Mills and her colleagues spent 14 months observing anemonefish in a coral reef in French Polynesia. Some of the sites were part of a global coral reef bleaching event (only three such events have ever been recorded, and they exist only because of climate change). In other sites the anemones remained intact despite the heat.

“We measured the number of eggs laid by each couple under these different conditions,” says Ricardo Beldade, a researcher with Portugal’s Marine and Environmental Sciences Centre and CRIOBE. “We measured before the heating events, during the heating event, and even after the heating event.” They also captured fish and measured their cortisol levels. The more of this hormone a fish (or a person) has, the more stressed it is. Stress is associated with a whole host of negative outcomes including increased weight gain (at least in humans), and decreased fertility.

“Very few anemonefish laid eggs during the bleaching event,” says Mills, who adds that they spent hours counting more than 5 million eggs on the photographs they’d taken. None of those eggs survived.

The picture was very different for those fish that were located in unbleached anemones. Their eggs hatched more or less normally, and their cortisol levels may reveal why: the anemonefish located on bleached anemones were incredibly stressed out, while those whose homes survived unscathed were much more calm.

“We’re showing that the mechanism for the reduced reproduction is the effects on the stress hormone,” says Mills.

The bleaching event at this particular reef lasted between four and five months, which means a decline in the population—but still allows the possibility of a rebound. In Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, where bleaching events occurred twice in one year and lasted longer, the effects may more catastrophic.

“If populations cannot replenish themselves because there are no new individuals coming in, then they wouldn’t be able to persist,” says Beldade. “They would go extinct.”

The study has repercussions for other species as well. Mills and Beldade calculated that as many as 12 percent of fish that call coral reefs home have a similarly close association with anemones. Their populations are at risk, as are other species like birds that depend on them for food.

There is, however, one tiny bit of hope. Despite exposure to warming waters, some anemones managed to survive just fine.

“In some of the sites where we have the breeding couples of anemonefish there could be five anemones, and say four of them would bleach and one wouldn’t,” says Wells. “We’d say, well, why isn’t that one bleaching? Is that one resistant to heating events?”

Wells and Beldade are collaborating with other researchers to better understand why certain anemones bleached and others didn’t. If successful, this could provide some insight in helping to protect anemone ecosystems in the future. But the one thing we know will stop sea anemones (and coral reefs) from bleaching is turning down the heat; that is, taking steps to mitigate climate change. A study released this past summer detailed the four actions that individuals can take to most effectively reduce the effects of global warming. Do it for Nemo.