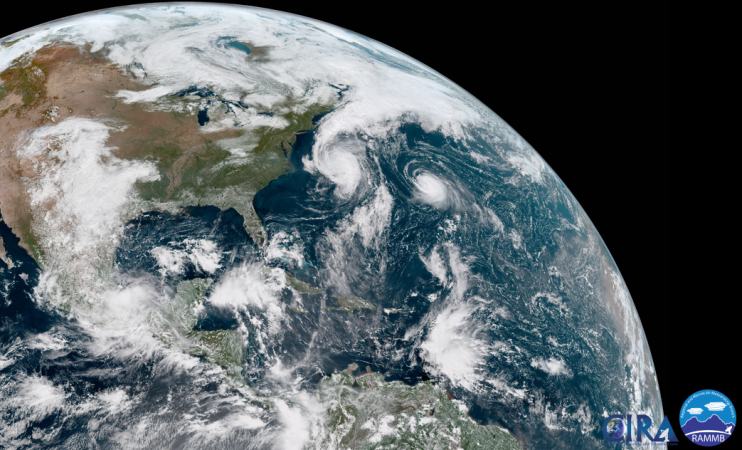

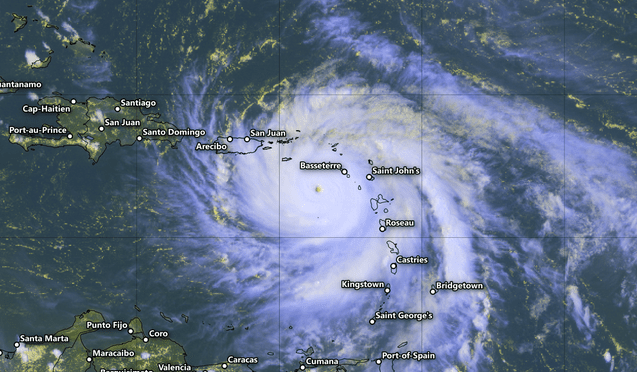

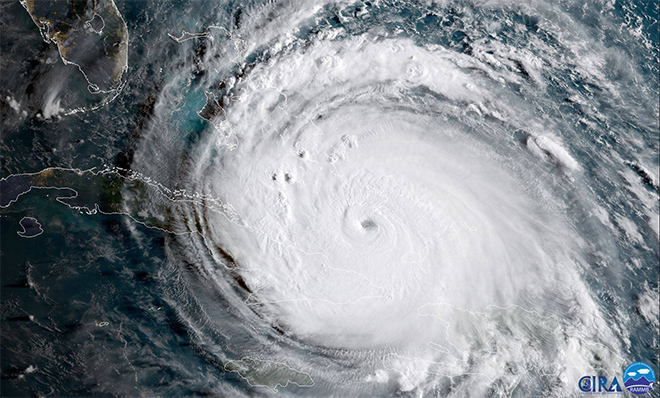

Hurricanes Harvey and Irma set records with their power, and the devastation they left in their wake. Irma has destroyed more than 90 percent of the structures on some Caribbean islands. All told, Harvey dumped 27 trillion gallons of water over Texas and Louisiana, swelling floodwaters that have been very slow to drain. Harvey has left its stamp on the landscape, too; the storm appears to have actually pushed a piece of the planet’s crust down by more than half an inch.

There are a lot of ways that major storms can impact the ecosystem. When a hurricane hits, animals can be swept away or stranded, trees splintered, and coastal lands swallowed up. “Hurricanes are like people—they’re really different, each one of them, in terms of how they express themselves,” says Tom Doyle, deputy director of the United States Geological Survey Wetland and Aquatic Research Center in Lafayette, Louisiana. This violent self-expression can be dictated by many features, from a storm’s path and intensity to the geology of the lands it passes over.

Hurricanes alter every ecosystem they pass through on both land and sea. And now that Irma and Harvey have spent their fury, scientists are returning to these areas to take stock of the damage. “With extreme events like this, we need to understand what’s happened, we need to learn from it, and hopefully that will help us when we face future scenarios to be more resilient,” says Bryan Brooks, director of the Environmental Health Science program at Baylor University in Waco, Texas.

The coast

When a hurricane hits, seawater surges into wetlands, bays, and estuaries. Some freshwater fish and other creatures can’t survive the onslaught of salt. Others, adapted to high salinity, suffer as the result of freshwater flooding. Vegetation can take a hit, too. As Hurricane Irma raged through Florida, it ripped up seagrass beds in Florida Bay.

Hurricanes can pull water from the coastline; several manatees were left stranded after Irma water drained from Sarasota Bay. Another crew of manatees had to be rescued from a small backyard pond. High above the flooding, birds can be blown hundreds of miles from their homes in a storm.

Hurricanes can also upset wetlands, which help absorb floods, filter water, and shelter a tremendous variety of plants and animals. “They support much of the fish and wildlife that we see around the Gulf Coast,” says Bren Haase, chief of planning and research at the Louisiana Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority in Baton Rouge. “The shorelines and wetlands also serve as our first line of defense against those storm surges, so as they absorb the brunt of the storm surge and unfortunately are lost, they’re not there for future events.” During Hurricane Sandy, wetlands prevented an estimated $625 million in flood damage to the East Coast.

Hurricanes can dramatically alter the seaside landscape as well; in 2005, more than 200 square miles of Louisiana’s coastline were obliterated by Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. “You can see, certainly, some dramatic and catastrophic changes in areas of our coast,” Haase says. “But it’s really the cumulative effect of numbers of storms over numbers of years that ultimately degrades the ecosystem.” Storms are predicted to become more fearsome thanks to climate change, which will only exacerbate the problem.

Haase and his colleagues are working to restore Louisiana’s coastal ecosystem and make it resilient enough to withstand storms and manmade disasters like oil spills. They are repairing barrier islands and shorelines and dredging up sediments and pumping them along the coast to rebuild marshes battered by hurricanes.

“No matter what we do here in Louisiana, we know our coast is going to change, our coast in the future is not going to be the same as our coast in the past,” Haase says.

On the other hand, hurricanes can also bring nutrient-rich sands to wetlands, and clear open sandy areas of the type favored by the endangered piping plover and other beach-nesting birds. Hurricane Sandy plowed a channel across New York’s Fire Island that has actually flushed polluted water out of Great South Bay, improving water quality and enticing fish, seals, and other marine life to take up residence.

Powerful storms can flood sea turtle nests, too. It’s likely that Irma wiped out many eggs on the nesting beaches of Florida, says Vincent Saba, a research fishery biologist at NOAA’s Northeast Fisheries Science Center. He and his colleagues will soon investigate how much damage the storm wrought. The good news is that sea turtles will make several nests throughout the season, so even if a storm wipes one out, others will have a chance to finish incubating.

The rivers and streams

As a hurricane pushes over land, it will continue to pour water into streams, rivers, and lakes. When these waterways swell and overflow their banks, they can engulf roads, destroy homes and bridges, and send animals scrambling for higher ground.

During Harvey, bats that lived on the underside of a bridge over Buffalo Bayou had to be evacuated by volunteers before they drowned in the rising waters. Alligators migrated inland to escape the rush of cold rainwater. Gator experts advised residents to keep their distance, but not worry too much—the reptiles were more concerned with getting to safety than picking a fight with people. “They got flooded out of their pond, they got flooded out of their river,” Chris Stephens, head of alligator relocation company Gator Squad, told The Washington Post. “They had to evacuate, too.”

For fire ants, it was another story—the rafts of ants that floated about in Harvey’s floodwaters were armed and eager to stream onto any person or boat that ventured near. Texans were also told to be on the lookout for snakes, raccoons, and other displaced wildlife. Exotic pets can escape during the chaos too, making it easier for invasive species to spread.

Meanwhile, the rivers themselves can be reshaped when storm water cuts into their banks, or when the floods fling rocks and sediments about and carry in trash and branches. As the leaves, wood and other organic matter that hurricanes churn up and leave behind rot, they will sap oxygen from the surrounding waters. As oxygen levels in rivers, lakes, and wetlands drop, fish begin to die. More than 180 million fish suffocated in Louisiana’s Atchafalaya Basin after Hurricane Andrew hit in 1992.

Floodwater also carries disease and toxins; Harvey and Irma have overwhelmed wastewater treatment plants, causing sewage to overflow into Texas and Florida cities and an aquatic preserve. Already, the fecal bacterium E. coli, which can sicken people if ingested, has been detected in floodwaters in Houston. Officials worry that the hurricane has also spread pathogens like cholera and typhoid, hazardous runoff from petrochemical refineries, and carcinogens from Superfund sites. Pollution released by hurricanes can also accumulate in fish and shellfish.

To find out how Harvey has altered Texan waterways, researchers will examine if the elevated floodwaters have carved changes into the streambeds and caused erosion along the banks. They’ll take water samples from tributaries and bayous and test for contaminants, or introduce common fish, shellfish, or insects to see if they thrive or die. “You take those samples back to the laboratory and you basically introduce…your canary in the coalmine,” Brooks says.

Ideally, researchers would be performing these studies every year all over the state so they would have a baseline to compare with the water post-disaster, Brooks says. But Texas is a big state, so there are gaps. Without these routine surveys, though, we cannot know what is normal for a given area.

It’s unclear how long it will take the ecosystem to recover from Harvey. “I don’t think anybody knows; with the type of event that’s just occurred, we don’t really have data,” Brooks says. “The amount and the extent of the flooding in this scenario is so unique.”

The trees

Trees taking a beating during hurricanes, and some are better equipped to handle it than others. Palm trees are full of flexible tissue that lets them bend in the wind. Most trees, once the wind picks up to 70 to 75 miles per hour, will begin to be stripped of leaves and small branches. When a storm reaches Category 3 status, it can crack trunks or tip them over. “It’s getting twisted or mashed in such a way that it weakens and fractures,” Doyle says. Still, there are several Gulf Coast trees that fare better than their fellows. Bald cypress trees are one; live oaks are so sturdy that the Navy once used them to build ships.

The violence a hurricane enacts on trees can depend on its path. Hurricane Sandy, despite its long voyage as a tropical storm, was able to knock down an astonishing number of trees in the mid-Atlantic, Doyle says. The odd, perpendicular direction Sandy approached from let it stack water into an impressive storm surge that liquefied the soil, making trees easier to tip over.

With mangroves, it can be hard to predict. The mangroves along the Gulf Coast are short and scrubby, and may have been spared Harvey’s winds when they were submerged in floodwater, Doyle says. “I’d be a little surprised if the surge wasn’t high enough that there wasn’t any real direct wind thrashing of the tops of the mangroves,” he says. The trees may be elastic enough to survive being battered by waves, but it’s also possible that they were left underwater too long to survive. In Florida, the mangroves grow much taller, but are better anchored in the karst underlying their soil, which is harder than the silty ground Gulf Coast mangroves grow in. “The karst provides a platform on which the roots kind of bind,” Doyle says. However, “The winds were still killing and knocking down mangroves, I expect to see post-storm some forests that are laid down.”

Hurricanes can also contribute to the slow migration of marshes inwards from the coast. After a storm, the ground soaks up seawater carried in by the storm and becomes saltier. When coupled with a drought that has left the soil parched, the saltwater can settle in and make a hostile environment for trees. Over time, this can kill the trees in coastal forests. “Long after the storm is gone, those soils will still be at the higher [salinity] level,” Doyle says. Slowly, the area will transition into a ghost forest, and then a marsh.

Damaged forests are bad news for birds—Hurricane Katrina knocked out fruit-bearing trees that migrating birds rely on to boost their energy before they head over the Gulf, Doyle says. “They actually were displaced into other forest habitat that had more pines and things that they don’t eat…just to keep their energy levels up.” When Hurricane Hugo struck South Carolina in 1989, it destroyed the old-growth forests that host the endangered red-cockaded woodpecker.

Hurricanes spell trouble for farmers, too. Hurricane Irma has taken out half of Florida’s citrus crop this year after submerging the delicate roots of the fruit-laden trees for days. Sugar cane fields have been struck hard, too. In Georgia, about 30 percent of the pecan crop has been lost. In Cuba, miles of banana plantations have been damaged.

Hurricanes do come with a few silver linings for forests. By ripping away leaves and toppling trees, storms can open up patches of forest so that sunlight can stream in and new plants can grow.

“I’m not one of these alarmists, like, ‘Oh a hurricane happened everything is going to hell in a hand basket,’” Doyle says. “Yeah, we got a bunch of trees down all browned, but it’s not going to become a parking lot; it’s going to come back.”

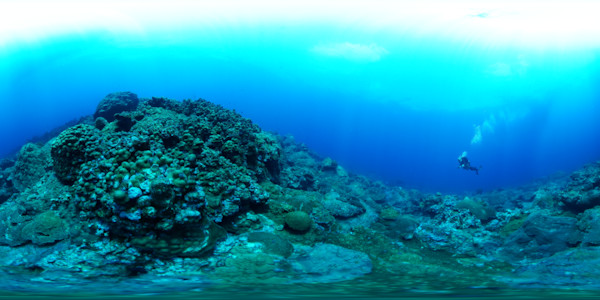

The reefs

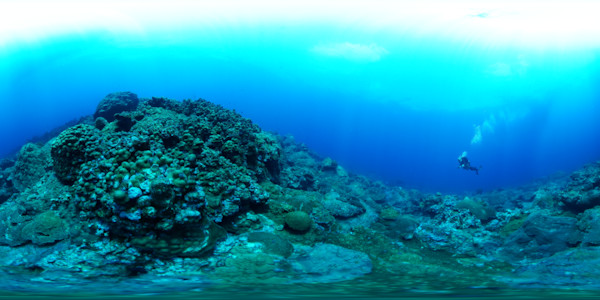

Even the seas aren’t safe from hurricanes. Sharks and other fish can sense that trouble is coming and head for deeper waters. Coral reefs, however, can get clobbered. Major hurricanes break and topple corals, sponges, and sea fans, and can bury reefs in sand, smothering them, Emma Hickerson, research coordinator for Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary, said in an email.

The sanctuary lies between 70 and 115 miles off the coasts of Texas and Louisiana. It is full of colorful reefs and is visited by sea turtles, whale sharks, and manta rays. It’s also vulnerable when storms roll through.

Water from about 60 percent of the continental United States drains into the Gulf of Mexico, carrying runoff that has created a dead zone, or dangerously low-oxygen area, the size of New Jersey. During a storm, this connection becomes even more of a liability; in 2005, Hurricane Rita battered the reefs and brought an unwelcome gift. “Rita flushed out the Texas and Louisiana coastlines, bringing with it discolored, polluted water,” Hickerson says. The water hung around for about two months. The corals appeared to have recovered well by 2008—”in time for Hurricane Ike to come barreling through and repeat the physical damage,” Hickerson says.

Now, the sanctuary faces a new threat. Hickerson and her colleagues believe that Harvey did not pass close enough to severely damage most of the area’s reefs. They are more concerned about the prodigious amount of rain that fell along the Texas coast, which may eventually make its way out to Flower Garden Banks. The team has spotted a plume of polluted freshwater in satellite imagery making its way towards the sanctuary. When it arrives, it might dilute the seawater the corals thrive on or poison them directly. The dirty water might also make the water turbid, blotting out the sunlight corals need to keep their symbiotic algae happy.

Flower Garden’s research team is scuba diving to look for damage and collect samples of the habitat before the freshwater intrudes, Hickerson says. It’s hard to tell when the plume will reach the sanctuary; this depends on the currents and wind. The best-case scenario would be for the currents to keep the fresh and polluted water north of the reefs.

Nothing can be done to stem the flow or clean it up. “I am optimistic that the reefs will recover from this storm, as long as the plume does not impact them,” Hickerson says.

Occasionally, hurricanes do help reefs out by carrying in cooler water, she says. This puts a halt on coral bleaching, which happens when corals become stressed by warm temperatures and expel their algae tenants.