Tartufo, the rosy-faced lovebird, has more limbs than you think. He’s got two wings, which, of course, he uses to fly. He’s got two legs, which he uses to grab branches and hop around the canopy. But when faced with an especially steep tree, he relies on a third: his head.

Based on climbing experiments published this month in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society Biological Sciences, rosy-faced lovebirds—a type of diminutive parrot—are members of a rare few vertebrates that walk with an odd number of limbs.

Plenty of animals have what the study’s senior author, Michael Granatosky, calls “effective limbs,” like a tail that acts as a tripod. But fewer actually use a spare limb to push or pull themselves along. “Now we’re talking about things that are a lot rarer in evolutionary history,” says Granatosky, who studies the evolution of locomotion at New York Institute of Technology. Kangaroos use their tail like a spring to jump, and spider monkeys climb through trees with a dexterous tail. “But “for the first time with these parrots, [we’ve found] an animal that uses its head as a propulsive limb”

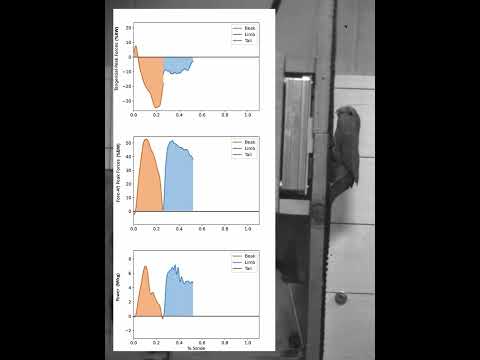

To sort out how parrots use their heads, the team set up a “runway” containing a small pressure sensor that detected pushing and pulling motions. That allowed them to distinguish when a bird was just hanging on for dear life by the mouth, or when it was actually pulling itself along. The six rosy-faced lovebirds in the experiment were all able to do neck-pull-ups to climb.

Granatosky has a pet cockatiel, Rex, says Melody Young, the paper’s lead author, and a graduate student at the New York Institute of Technology. “So he would watch his parrot climbing and think ‘I want those forces.’”

But bigger parrots, like macaws, are tougher study subjects, because they bite hard enough to take a finger off if they’re grumpy. So instead, the team turned to rosy-faced lovebirds as a model because they’re sweet tempered. If anything, says Young, “they’re too friendly.”

“They would climb on you as much as they would climb on the runway,” Granatosky adds. “The hardest part is trying to keep them on there.”

But the lovebirds aren’t defenseless. To climb with their heads, their necks have to be about four times stronger per body weight than ours, and deliver bites with a force fourteen times their body weight. “If they get feisty and we’re not wearing gloves,” says Granatosky, “they can draw some blood.”

The parrots don’t always walk with three limbs. By tilting the runway, the researchers showed that they only began to use their mouths when going up a 45 degree slope, and relied more and more on their head as the runway got steeper.

[Related: Crows and ravens flexed smarts and strength for world dominance]

For the lovebirds, that makes the head a close analogue to the way people use our arms when rock climbing. Right now, Young is planning a series of human experiments involving treadwalls—a short section of rock climbing wall that moves like a treadmill—to understand how both novice and expert rock climbers actually move up a wall. The experiments are a jumping off point to study treatments for people who need to develop shoulder and leg strength, and imagine new ways of building climbing robots.

The sheer oddity of using a head to move hints at something mysterious about the parrot’s brain. When animals move, their brains produce repeating patterns to govern the sequence of steps—“it’s the reason you don’t have to think about walking, right?” says Granatosky. Parrots, unlike other birds that hop up trees, “move just like we do. Everything is left, right, alternating movements.” Being able to incorporate a third, asymmetrical limb movement into that sequence is “weird from an evolutionary perspective,” he says.

Since publishing the paper, Granatosky says that people have reached out with their own stories about tripedal movement—or even head-assisted tree climbing. “The weirdest email was about hunting dogs,” he says. “Dogs that are trained to put animals in trees, a small percentage of them learn to use their head to climb the tree.” As weird as head-propelled climbing seems, it might be more common than evolutionary biologists currently realize.