Thousands of years ago, the United States was home to vampires. Fossils of multiple vampire bat species have been found in California, Texas, Florida, Arizona, and other states, dating from 5,000 to 30,000 years ago. Since then, winters in the southern United States have become cooler. But vampire bats still roam Mexico, Central America, and South America. And now, they are on the move. The common vampire bat (Desmodus rotundus) is pushing into new territory in both North and South America, and bringing new variants of rabies along for the ride.

New research indicates that the bats’ population is on the rise at the northern edge of their range, and they may even return to the United States as climate change renders parts of Texas and Florida hospitable once more. “They’re very social and gregarious animals that have coexisted with humans for a really long time,” says coauthor Antoinette Piaggio, a molecular ecologist at the U.S. Department of Agriculture. “We’re not trying to portray these animals as something we should all be scared of.”

It could be that an infusion of blood-sucking bats will not even lead to a noticeable rise in rabies in the United States. Still, scientists must prepare for a possible vampire bat invasion. They are trying to predict where the bats will arrive, what the consequences will be, and how to prevent vampire bat-borne rabies from spreading into new places.

Returning stateside

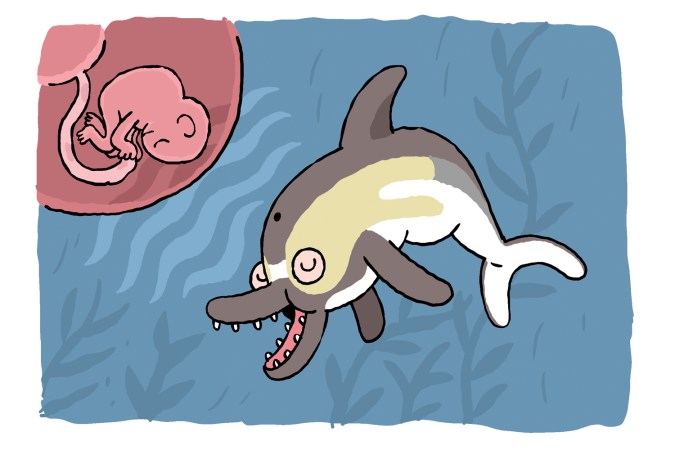

As the only mammals to feed solely on blood, vampire bats are well suited for their special meals. They can detect where blood is flowing closest to the surface of an animal’s skin, recognize an individual animal’s breathing so they can prey upon it night after night, and escape if the animal stirs by springing from all fours right into flight.

Vampire bats are not, however, well adapted to the cold. The 2-ounce bats, which are found from southern Argentina to northern Mexico, are kept in check by chilly winters. Vampire bats are thought to be limited to areas where the average coldest temperatures don’t dip below 50 degrees Fahrenheit. Yet in recent years, people have started reporting vampire bats at higher elevations and farther north than before, Piaggio says.

Within the past 5 years, vampire bats have been documented within about 30 miles of Texas. The bats are multiplying in areas where they were once uncommon, Piaggio and her colleagues suspect. They’ve taken wing tissue samples from hundreds of bats, and found evidence in the animals’ DNA that the population had grown rapidly and recently in the northeastern edge of their range in Mexico.

But speed is relative. The bats could have started increasing in the past decade—or hundreds of years or more in the past. “It could have been as far back as when Europeans first arrived,” Piaggio says. The livestock that the colonists brought with them in the 15th and 16th centuries could have provided the bats with more prey, allowing them to increase their numbers. In future, examining more of the bats’ genomes could help the team pinpoint the their rise more precisely, says Piaggio, who published the findings in the journal Ecology and Evolution in June.

If the bats are marching north, they might find appealing real estate in the southernmost United States. Piaggio and her colleagues are investigating where vampire bats could cross the border using current and worst-case future climate conditions through about 2070.

“A very small part of the southern tip of Texas could currently be representing suitable habitat for vampire bats, and so it’s possible that vampire bats could currently be spreading north,” says team member Mark Hayes, senior bat ecologist at Normandeau Associates, an environmental consulting firm headquartered in Bedford, New Hampshire.

In the next few decades, other parts of southernmost Texas and the southern half of Florida could become warm enough to host vampire bats. Hurricanes could blow the bats from Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula into Cuba and then Florida, Piaggio says.

While vampire bats could perhaps settle in a sliver of southern Texas, there’s no way to know if or how soon they might arrive. It’s possible that incursions into the southern parts of Texas would be a seasonal affair. “They’re very social animals, and even if males disperse they might not stay because they couldn’t set up a harem of females and reproduce,” Piaggio says.

The vampire bats would likely only colonize a pretty small area. What’s more, rabies doesn’t affect a large portion of the population, although the wounds the bats leave behind can still harm an animal’s health if they become infected. “It might even be that we end up with vampire bats and no or very little rabies transmission,” Piaggio says. “Maybe they would feed on feral swine and deer and we wouldn’t ever really pick it up.”

If the climate in southern Texas and Florida shifts and winters become warmer, the bats would have a fair shot of surviving up north, says Daniel Streicker, a disease ecologist at the University of Glasgow in Scotland. “I think it’s going to be a pretty slow invasion,” he says. But, “I don’t see why they couldn’t move up into the U.S.”

Ready to mingle

Understanding where vampire bats from different areas meet up could help scientists predict how rabies will spread. For now, Streicker says, rabies is not found in vampire bats along the western coast of South America. But that may change within a few years.

To estimate how quickly the virus could travel, Streicker and his colleagues pored over records of past rabies outbreaks, noting which version of the virus was responsible for each. They also captured vampire bats from around the country, and examined variants of the virus that had shown up in different areas. The team found genetic evidence that male vampire bats are responsible for bringing rabies to new territory, likely when they leave their families to seek out a harem of females to breed with.

The team also found genetic similarities in bats on the eastern and western slopes of the Andes. Vampire bats, it seems, are not blocked by the mountains, and could bring rabies with them over this route. Already, farmers and vets are reporting vampire bat bites on livestock at higher and higher elevations in the Andes. The researchers have calculated that vampire bat-borne rabies could reach the Pacific coast of South America around 2020.

Streicker has also documented “waves” of genetically related versions of rabies moving through livestock in Peruvian valleys. This indicates that variants of the virus carried by vampire bats hadn’t existed in these regions previously, and are only just arriving. Local farmers told Streicker that they were used to dealing with vampire bats, but the rabies was only a recent problem. He then examined strains of the virus from around the country and saw a similar pattern, implying that rabies is on the move in many places.

It’s not clear why this is happening now. It could be that vampire bats are moving into new areas, and the virus takes a few years to catch up. Climate change could be making mountains less impassible, allowing bats from previously isolated colonies to meet.

Humans might also be unwittingly bringing vampire bats together. As farmers bring livestock into new areas, the bats could feast over broader terrain and encounter bats from neighboring colonies. And when people build tunnels and mines, they create new housing for bats in areas that might have otherwise lacked tempting roosts.

Another possibility is that rabies has only been circulating in the vampire bat population for a couple centuries, and hasn’t had a chance to spread to every corner of the bats’ range.

Streicker is now studying the economic problems vampire bats cause by spreading rabies to livestock. Many of the communities where bat-borne rabies is now invading rely on small-scale subsidence farming. When a single cow sickens and dies, it can represent the loss of a month’s income. “It can be totally devastating,” Streicker says. “When they sell a cow, it’s going towards childhood education or towards repairing their houses.”

He’s heard that many people are giving up on raising animals altogether. “They’re either moving to cities or they’re switching to raising things like oranges or avocados, because it’s just so unsustainable to raise cattle in areas where there is rabies,” he says.

Bracing for impact

The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Rabies Management Program has begun to prepare for the possible arrival of vampire bats and any new strains of rabies they might bring to the United States. They are surveying cattle at cattle sales barns, feedlots, and on dairy farms for vampire bat bite wounds in Texas, Arizona, and Florida. In 2017, they examined more than 95,000 cattle, and did not find any vampire bite wounds. They are also educating farmers and wildlife biologists in the borderlands to recognize vampire bat bites.

Their goal is to minimize any risk to people, pets, and livestock without demonizing the bats. “While the mention of the word rabies strikes fear [into] people there are very straightforward ways to minimize the risk of being exposed,” Richard Chipman, the rabies management coordinator, said in an email. “Vaccinating pets and livestock and avoiding strange or sick acting wildlife remains the best first line of defense.”

These steps, however, will not halt the spread of rabies within the bat population.

“We can vaccinate humans and livestock all day long, but at the end of the day those species don’t contribute anything to the onward transmission,” Streicker says. Yet culling the bats hasn’t reliably worked to stop the spread of rabies, either, he says. In fact, this tactic can actually spread diseases even farther.

People sometimes try to kill vampire bats by lighting their caves on fire or attacking them with large sticks. This can drive the bats out to seek new homes, bringing rabies into new areas. “The bat has no reason to stay inside this cave [where] it’s being lit on fire and persecuted all the time,” Streicker says.

Another technique for killing vampire bats is to spread a poisonous paste on one bat’s back, then release it. When the bat rejoins its fellows, they will begin to groom it and lick the poison from its fur. “Some of the ones that might be incubating rabies but aren’t sick yet might realize, ‘there’s something strange going on here, all of my friends are dying,’ and so they might fly farther away to try to escape,” Streicker says.

There might be a more effective way to slow the virus’s spread: swapping the poison out for vaccines. So far, oral vaccines seem to work well in captive vampire bats, including when the bats swallow it while grooming each other. For now, though, these vaccines are still in development and need additional safety testing; it will probably be a few years before they can be tested in the field.

Vampire bats do pose a substantial risk in terms of their ability to spread rabies, and they are more abundant now than ever before, Streicker says. In Latin America, they are the main cause of rabies outbreaks in people. But on the whole, it’s rare for people to be bitten by vampire bats in agricultural areas; if there are livestock around, the bats tend to feed on them rather than people. People can get rabies from infected livestock, but in practice this doesn’t happen much, Streicker says.

Vampire bats have the potential to do a lot of damage; in some parts of Mexico, rabies kills up to 20 percent of unvaccinated cattle. But in the United States, their impact is likely to be more limited.

“The arrival of this unique and interesting species and eventually a novel (at least in the U.S.) rabies virus variant is not a catastrophic event or cause for significant alarm,” Chipman says. Even if it sounds a little bit spooky.