The US Army wants a new human-portable missile that soldiers can use to shoot down aircraft. Looking to replace the venerable Stinger anti-air weapon, the Army put out a request for information on March 28, and wants the weapon in production by 2027. A new anti-air weapon program for the Army has long been in the works, but Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has cast the issue in stark relief. The ability of soldiers on the ground to destroy aircraft, or at least make the threat of airstrikes a risk to pilots, has greatly constrained how Russia is fighting the war.

The solicitation dryly notes that “The current Stinger inventory is in decline,” which is one way to describe the US Army sending thousands of the missiles from its own inventory to Ukraine’s military. The missiles cost $38,000 apiece, which partly explains why units like the 173rd Airborne Brigade had trained with replicas instead of live missiles, a practice that changed this month.

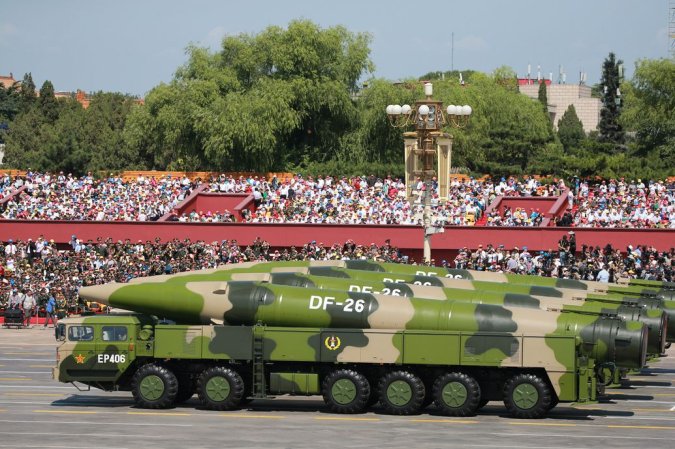

These missiles join even older anti-air weapons, like the Soviet-made Strela anti-air missiles Germany sent to Ukraine, in bolstering the defense of Ukraine without actively joining the fight in the sky above. These weapons are both MANPADS, or man-portable air defense systems, and both Strelas and Stingers were developed in the 1960s as an answer to jets and helicopters on the battlefield. The missiles have also been incorporated into launchers on vehicles, which can carry more weapons and incorporate more advanced sensors to detect and track hostile aircraft before firing.

A combination of human-carried and vehicle-mounted anti-air defenses allowed Ukraine’s military to inflict significant damage on Russian aircraft flying low attack runs, an approach that in turn drove Russia’s air force to adopt less accurate higher-altitude bombing runs as a means of preserving aircraft.

In 2022, human-carried anti-air missiles still have a role in attacking helicopters and planes, but they will also need to operate in skies full of drones, with far better sensors and countermeasures than were possible decades ago. To understand the Stinger replacement, first it helps to understand the Stinger.

Meet the old Stinger

“The basic Stinger weapon is a Marine-portable, shoulder-fired, infrared (IR) radiation homing (heat-seeking) guided missile that requires no control from the gunner after firing,” explains the Marine Corps’ Low Altitude Air Defense Gunner’s Handbook. Complete with a launcher, it weighs 34.5 pounds, of which 12.5 pounds is the missile, which itself contains 2.25 pounds of explosive warhead.

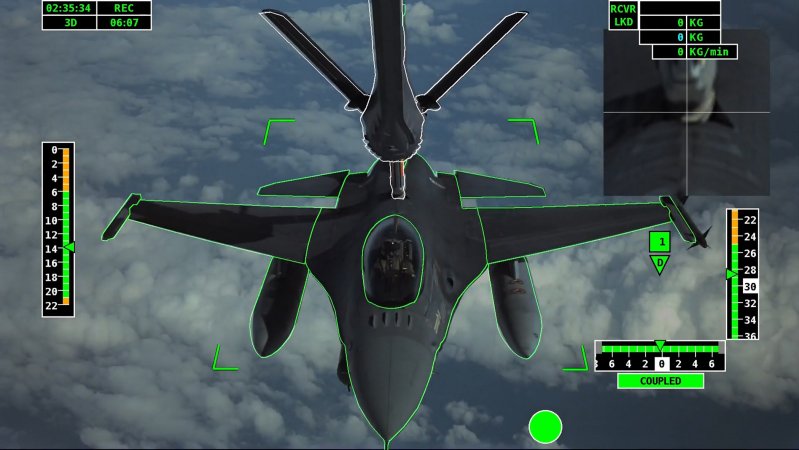

It is useful against fast, low-flying aircraft used to attack people, vehicles, or buildings on the ground. It can start tracking targets at a range of 15,700 feet, or just shy of 3 miles, and it can hit vehicles as far away as 12,500 feet, or 2.4 miles. Upgraded and modern versions of the missile have a processor to help ensure it only targets hostile vehicles and not friendly ones, and these missiles also carry a different processor that’s useful against infrared countermeasures.

Heat-seeking against the engine of a helicopter or jet is a particularly reliable way to find and track the vehicle.

“The Stinger seeker can discriminate between radiation from a small point source such as the tailpipe of a jet and large background sources such as clouds and terrain,” the manual notes. “Except for the sun, the target’s engine exhaust is usually the smallest and hottest object in the environment and will be tracked by the missile seeker.”

The missile design dates back to the 1960s, when it replaced earlier Redeye shoulder-fired missiles that struggled to catch, pursue, and correctly identify enemy aircraft. One of the big changes in design of the Redeye II, which became the Stinger, was to move some sensors from the missile itself to the launcher component. Stingers entered into service in the 1980s, and besides the US military, they were famously distributed to insurgents fighting against the Soviet Union in Afghanistan starting in 1986.

The new Stinger

In seeking a Stinger replacement, the Army wants to keep much of existing Stinger infrastructure in place. The notice says the new “system must be capable of integration with the Stinger Vehicle Universal Launcher,” and also that it must be soldier-portable.

What will be new in the Stinger replacement, then, is that it must do everything an existing Stinger can do, but better, with an explicit call for better target tracking and greater range than exists at present. These missiles must also destroy helicopters and planes “with capabilities equal to or greater than the current Stinger missile,” as well as destroying “Group 2-3 Unmanned Aircraft Systems.” Russia’s Orlan-10 drones, used for artillery spotting and scouting in the Ukraine invasion, falls on the smaller end of that category. The Bayraktar TB2 drone, made by Turkey and prominently featured by Ukraine’s military, is just on the edge of the maximum size of Group 3.

Drones like the Orlan-10 and TB2 are features of modern warfare, used by major and mid-sized militaries, and play a role in combat that the drones used for scouting in the 1960s and 1970s never could. It makes sense, then, that any new anti-air weapon should be capable of protecting soldiers from aerial discovery or drone-guided artillery barrages.

One way to defeat those drones, included in the posted notice and in videos like this from Stinger-maker Raytheon, is a “proximity fuse.” Instead of having to hit the drone directly, a Stinger with a proximity fuse has to just get close enough that it can catch the drone in the blast radius of its own detonation.

While the new notice is explicitly for Stinger missiles that can be used from vehicle-based launchers, because the same missile must be compatible with existing launchers, it can likely be thought of as a planned replacement for all existing inventory of Stinger missiles, both human- and vehicle-carried.