Military camouflage, you may think, is easy: you just slap weird shapes in tones of green, beige, blue, or gray on hardware or clothes. But camouflage today is much more sophisticated than that because equipment and people must be hidden not only from the enemy’s eyes, but also from their infrared cameras and radars. Of course the ultimate—and for the moment unattainable—objective is invisibility, but Harry Potter’s cloak remains the stuff of fiction and CGI.

Militaries and defense companies use, and are working on, two completely separate camouflage technologies: static, such as paint or textile that doesn’t change once applied, and dynamic, which adapts in real-time to its environment. While the former is well-established, the latter has yet to be bought by an armed force.

“The primary goal is to merge the object with its background,” Mike Stewart, director of research and innovation at QinetiQ, a British defense technology group, told Popular Science at an arms show in London in September.

To do so, “you need to hide shape, shine and shadow,” explained Peter Somerville, business development manager for Lockheed Martin. And because “nothing in nature is flat,” as he said, camouflage textiles are full of holes or little flaps that stick up every which way. Sometimes it’s the actual shape of these holes in the netting that give it its anti-radar characteristics by absorbing and diffusing those radar beams.

Haute couture camouflage

That’s the case with the Multisorb camouflage used by the US Navy SEALs and made by MBDA, the European missile manufacturer. A Multisorb-outfitted vehicle looks like it was clothed by a fashion designer with a taste for deep ruches, bows, folds and layers (in military colors, naturally). These layers trap the air, giving the camouflage its effectiveness against infrared detection, which “sees” heat.

“The idea was to make folds to improve the air circulation, which helps hide heat so that the air which is passing behind the camouflage appears at the same temperature as the ambient air,” its French inventor, René Brugieregarde, said in a telephone interview. Multisorb is made of two layers of polyester netting, “because polyester absorbs and reflects the ambient air temperature,” he explained.

The camouflage panels are attached to the vehicles with hooks and magnets enabling the Multisorb-outfitted vehicle to drive at up to 75 mph with no risk of the camouflage flying off.

Like oil on water

Swedish company Saab Barracuda, which has cornered the western world’s camouflage market, unveiled its new textile camouflage at the show. Named ARCASe—that’s Advanced Reversible Camouflage Screen emissive—it consists of textile panels printed on both sides with different colors and visual patterns. But when folded, the textile seems to move, much like oil on water, or a mirage. And this quality is very effective at hiding the shape, shine, and shadow of whatever it is covering.

But ARCASe is not just visual patterns. Lisa Nigran, Barracuda’s director of marketing, said the textile is covered with a coating that remains an industrial secret. “The textile and coating work together to break the thermal signature,” she said. This means that the heat of a vehicle’s engine, for example, or its wheels, are both masked and disrupted to blend in with the background.

This kind of product, which costs about 1 percent of the price of the vehicle, according to Nigran, “is aimed at high-tech armed forces with high-tech enemies.”

Color shifting

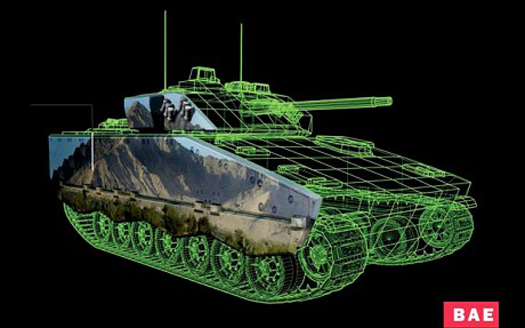

Dynamic camouflage, the kind that changes to match its surroundings, “is definitely not science fiction and is ready for implementation,” according to BAE Systems Hagglunds, which makes what they call the Adaptiv “cloak of invisibility.”

Well, invisible to thermal sensors at least. It’s made up of hexagonal modules about the size of a compact disc; they can be cooled or heated very quickly and can each change color in order to create different patterns. Images can be projected onto the panels to make the tank look like an ordinary car instead. The company says in the future the technology could be used on ships and aircraft “which might help to turn a helicopter into a cloud or a warship into a wave.”

The French defense ministry, and defense company Nexter, are working on a similar idea: Caméléon is a system of tiles that change color in real-time. Sensors all around the vehicle capture the dominant colors of the environment and transmit the data to a computer that determines which is the best camouflage at that instant. The liquid-crystal tiles can show one of eight colors: red, blue, green, cyan, magenta, yellow, black, and white. They also adapt to the light so are bright in the day and dull at night. The system would be powered by the vehicle’s own batteries.

Nexter should have a 10 square-foot demonstrator ready for next year. The system could even be miniaturized and embedded into textiles for soldier battledress!