After many delays, the biggest space telescope of all time has finally gotten off the ground. The 14,000-pound James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) launched at 7:20 am Eastern on December 25 from the Guiana Space Center in Kourou, French Guiana. You can watch the event unfold here:

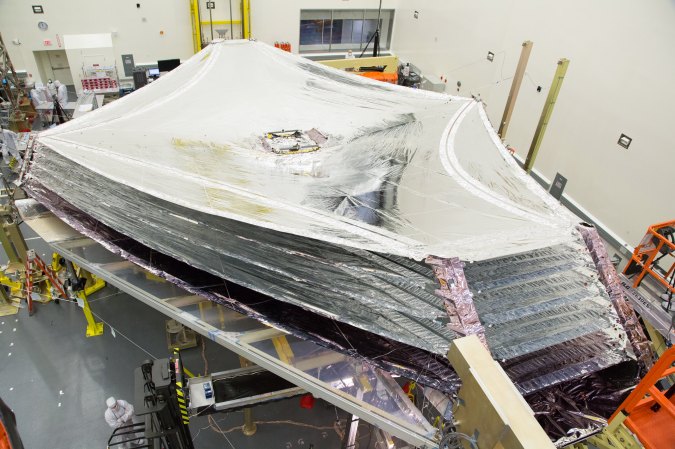

In development since the late-90s (and technically 14 years behind schedule), JWST is a souped-up feat of space engineering. With “a mirror over 20 feet across, a tennis-court sized sun shade to block solar radiation and four separate camera and sensor systems to collect the data,” it’s powerful enough to peer at galaxies about as old as the Milky Way and to evaluate the atmospheres of mysterious exoplanets.

“Webb started when I was in grade school,” Caitlin Casey, an astronomer at the University of Texas, recently told PopSci. “It’s really phenomenal that as a species that is bound ultimately to the planet that is home, we’re able to peer so far into the cosmos as to see its own beginnings. That’s pretty profound.”

At 7:48 am, about 30 minutes after launching from the Guiana Space Center on the Ariane 5 rocket, JWST detached and mission control successfully deployed its five towering solar panels, which power its instruments and communications systems. The telescope is set to complete its first trajectory correction on Saturday evening.

“This is a great day, not only for America, for our European and Canadian partners, but it’s a great day for planet Earth,“ said NASA Administrator Bill Nelson. “We’re going to discover incredible things we never imagined, and isn’t that typical of this team, that the impossible becomes possible.“

JWST still has a bit of a journey ahead of it. According to its mission schedule, the telescope will undertake another correction maneuver in 2.5 days, just after it crosses paths with the moon. After that, mission control will start unfolding JWST’s sunshield and other components that were locked down or tucked away for safekeeping during the launch. Several weeks later, when the sunshield has helped to cool JWST down, the telescope’s flight software will turn on and guide it into its final orbit nearly 1 million miles away from Earth.

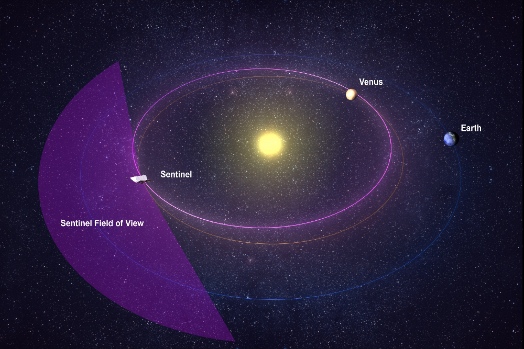

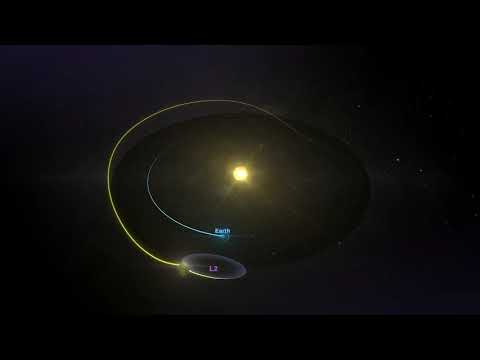

The telescope will hover in a gravitationally stable spot known as Sun-Earth Lagrange Point 2 (L2), which will allow it to stay aligned with Earth as the planet orbits around the sun. Because JWST is primarily designed to observe infrared light, it’s crucial to keep it protected from any heat or light that could drown out the faint signals of distant stars and planets. With the sunshield, it should only reach a maximum of 185 degrees Fahrenheit on the side exposed to solar rays; the opposite side, where the telescope’s mirrors, detectors, and other delicate instruments live, will remain at a chilly -388 degrees Fahrenheit. The intriguing gravitational properties of the Lagrange Point ensure that JWST won’t flip around and fry its sensors while the solar panels and computers freeze.

JWST should be ready to begin its primary scientific mission in roughly six months. The $10 billion telescope is intended to last at least five years once its mission begins, and carries enough propellant to operate for a decade. NASA has said that refueling the telescope or servicing it should it need repairs would be too costly and complex, given its distance from Earth.

For now, scientists around the world are holding their collective breath as they wait for this long-anticipated piece of technology to start yielding data.

“Now we have to realize that there are still innumerable things that have to work and have to work perfectly,“ Nelson said, “but we know that in great reward there is great risk.“