A type of statistical analysis used to study high-energy physics and stock market fluctuations could yield a new angle of attack in the fight against the virus that causes AIDS. A surgical strike on specific, steadfast sectors of HIV could lead to new drugs or vaccines, according to a new study.

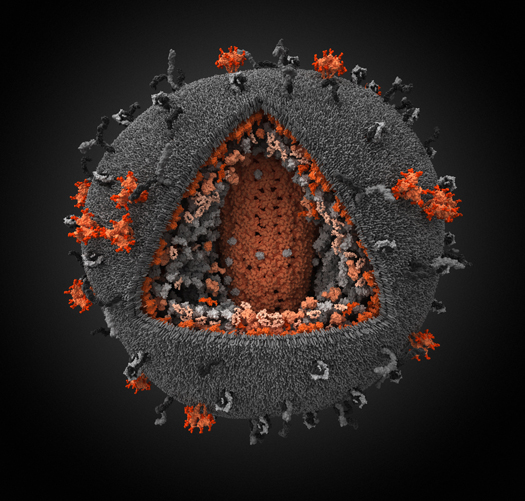

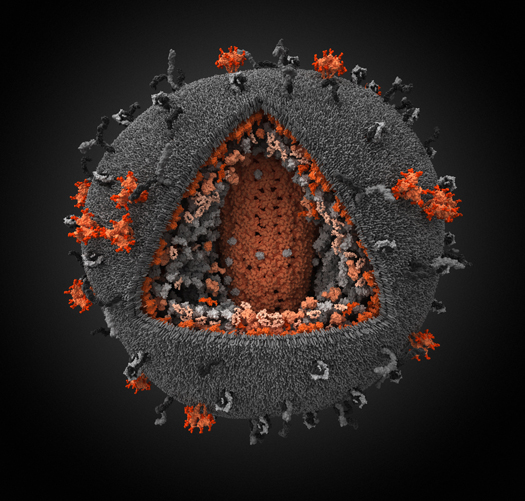

HIV has been so difficult to fight in part because it is such an adept mutant. It produces sloppy copies of itself as it replicates, leading to many variations that can withstand drugs and vaccines. And it can produce 100 billion new virus particles every day, as Ed Yong points out over at Discover, which leads to lots and lots of copies. Broad-spectrum drugs or vaccines can’t do very much against a target that morphs so quickly.

But not all the pieces of HIV mutate with such abandon, according to this new study. Some groups of amino acids known as HIV sectors are somewhat less fickle, staying the same while the rest of the virus morphs, according to researchers at the Ragon Institute, a research group bridging MIT, Harvard University and Massachusetts General Hospital. Researchers believe these sites must remain unchanged for the virus to survive and replicate properly.

Researchers led by HIV research pioneer Bruce Walker and MIT chemical engineering professor Arup Chakraborty say this stalwart section of the virus can be turned against it. If the immune system can be trained to attack all the amino acid portions in an HIV sector, the virus will either have to mutate to thwart the attack — thereby undermining its structural integrity, crippling itself — or not mutate, which would render it helpless against drugs or vaccines.

This new targeted approach came from Chakraborty, who thought Walker and colleagues were too limited in their search for solutions, Yong reports. The team turned to random matrix theory, developed in the 1950s to solve nuclear physics problems and which has been used to analyze stocks, as the Wall Street Journal notes. It can pinpoint correlations between groups of objects, so it can assess how one stock is linked to other groups of stocks, for instance.

Working with HIV proteins taken from a massive database, the team used random matrix theory to analyze HIV’s genetic code and find groups of amino acids whose mutations were coordinated. The segment that mutated the least was dubbed sector 3, on an HIV sector known as Gag, which makes up HIV’s honeycombed inner shell. If the shell mutates, the honeycomb won’t lock together, and the virus would collapse.

“Multiple mutations within this sector are very rare, indicating previously unrecognized multidimensional constraints on HIV evolution,” the authors write in a paper on their research, which is published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Incidentally, a rare group of patients who can fight HIV without drugs — known as “elite controllers” — use their own immune systems to attack sector 3.

All this suggests a new way of thinking about HIV treatment, the WSJ and others point out. Perhaps HIV drugs should dispense with the full-on assault and opt for targeted strikes instead.

Buoyed by this research, other teams are reportedly already planning new animal studies to test just that.