A new heat-sensitive gel and glue combo is a major step forward for cardiovascular surgery, enabling blood vessels to be reconnected without puncturing them with a needle and thread. It represents the biggest change to vascular suturing in 100 years, according to Stanford University Medical Center researchers.

Sutures are an effective way to reconnect severed blood vessels, but they can introduce complications, for instance when cells are traumatized by the puncturing needle and clog up the vessel, which can lead to blood clots. What’s more, it’s difficult to suture blood vessels less than 1 millimeter wide, the Stanford team said. One of the authors on this study, Stanford microsurgeon Dr. Geoffrey Gurtner, was inspired to work on this problem a decade ago after a five-hour surgery in which he reattached the severed finger of a year-old infant, according to Stanford Medical School.

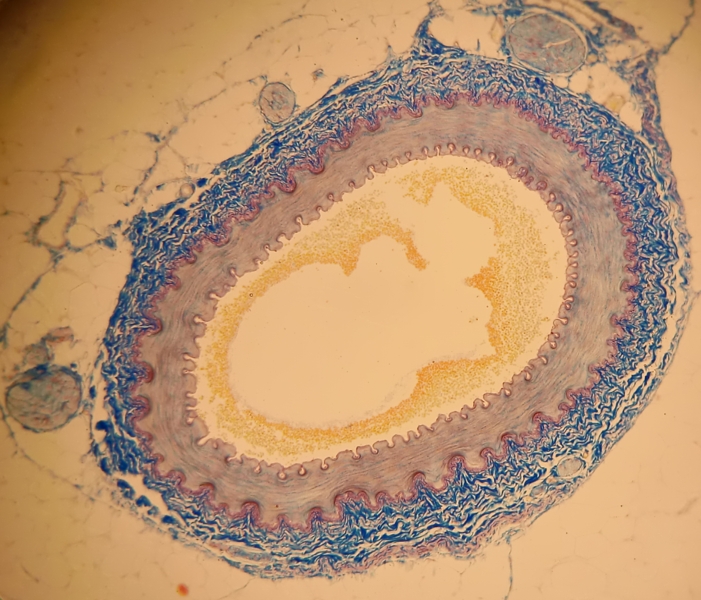

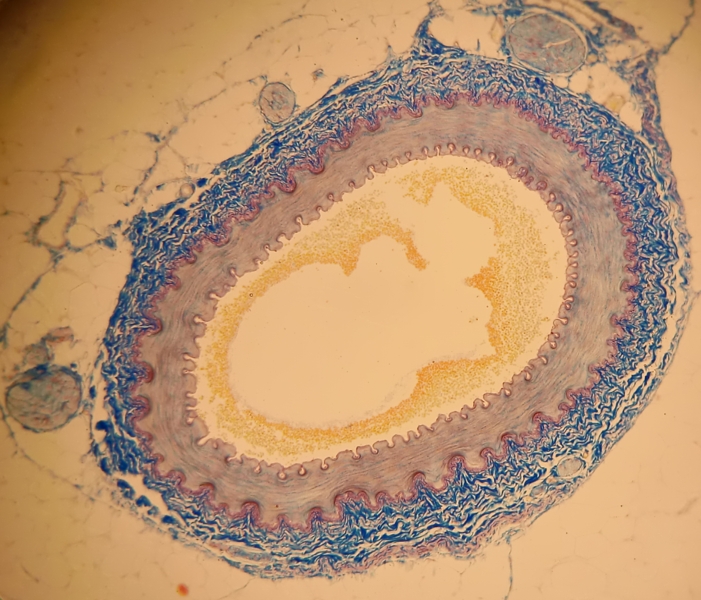

Sutures work by stitching together sides of a blood vessel and then tightening the stitch to pull open the lumen, or the inner part of the vessel, so the blood can flow through. Gluing a vessel together instead would require keeping the lumens open to their full diameter — think of trying to attach two deflated balloons. But dilating the lumen by inserting something inside introduces a wide range of problems, too.

Gurtner initially thought about using ice to fill up the lumen instead, but that meant making the vessels extremely cold, which would be too time-consuming and difficult on the operating table. He approached an engineering professor, Gerald Fuller, about using some kind of biocompatible phase change material, which could easily turn from a liquid to a solid and back again. It turned out Fuller knew of a thermo-reversible polymer, Poloxamer 407, that was already FDA approved for medical use.

Working with materials scientists, the team figured out how to modify the polymer so that it would become solid and elastic when heated warmer than body temperature, and would dissolve into the bloodstream at body temperature. In a study on rat aortas, the team heated it with a halogen lamp, and used the solidified polymer to fill up the lumen, opening it all the way. Then they used an existing bioadhesive to glue the blood vessels back together, a Stanford news release explains. The work was published in this week’s issue of Nature Medicine.

The polymer technique was five times faster than the traditional hand-sewing method, the researchers say. It even worked on superfine blood vessels, just 0.2 millimeters wide, which would not work with a needle and thread. The team monitored test subject rats for up to two years after the polymer suturing, and found no complications.

“This new technology has potential for improving efficiency and outcomes in the surgical treatment of cardiovascular disease,” the authors say.