A Dutch scientist found two baby earthworms wriggling around in soil that is supposed to replicate the surface of Mars. But we’re still pretty far away from gardening on the red planet.

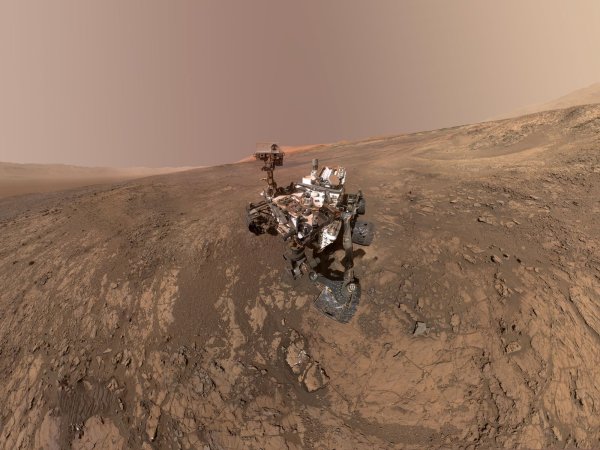

For now, scientists don’t have access to real Martian soil. So Wieger Wamelink, biologist at Wageningen University, bought a simulation from NASA at a hefty $2,500 for about 220 pounds (he created a crowdfunding campaign to help with the costs). The U.S. space agency fetched that dirt from a volcano in Hawaii and the Mojave desert, then sterilized it to copy the lifeless Martian environment. Wamelink and his research team then put the simulation soil through a Martian colony scenario. They were enthusiastic when they added adult worms that not only survived, but reproduced. “That was way beyond what we expected,” says Wamelink.

The discovery that earthworms could survive on the red planet would be thrilling. These underrated annelids are crucial to a healthy ecosystem on Earth. They’re living super-composters, eating dead plants and pooping out productive soil. If human colonies could breed them, their crops would fare better.

But the process of recreating a stranded Matt Damon scenario is not all that scientific for the time being. After receiving the soil from NASA in 2013, Wamelink planted a variety of seeds. To his delight, tomato, wheat, cress, field mustard, and a wild plant called stonecrop grew. He checked that batch for heavy metals, but put a roughly equal amount of plants back into the soil to imitate what would have happened without human intervention. After that first year, he started putting the actual plants back into the soil, but also added pig slurry as a stand-in for human feces.

Future Martians probably wouldn’t do this, according to Andrew Palmer, a biology professor at the Florida Institute of Technology. “It’s highly unlikely we will put feces in agriculture of any kind in the soil,” he says. “Human feces are a horrible vector for disease, and I don’t know how many pigs will be on Mars.”

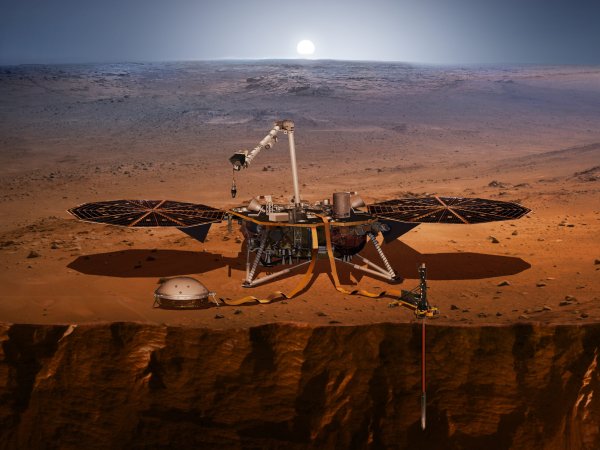

But the dangers from spreading human poop—diarrhea, typhoid, cholera, polio and hepatitis—don’t compare to perchlorate, which the Phoenix Mars Lander found in Martian soil in 2007. This compound, which humans sometimes put in propellants and packaging, affects the thyroid and lungs. Martians would need to get rid of this substance before planting anything in the soil, and other space missions that collect larger soil samples may bring back news of other less-than-delicious substances.

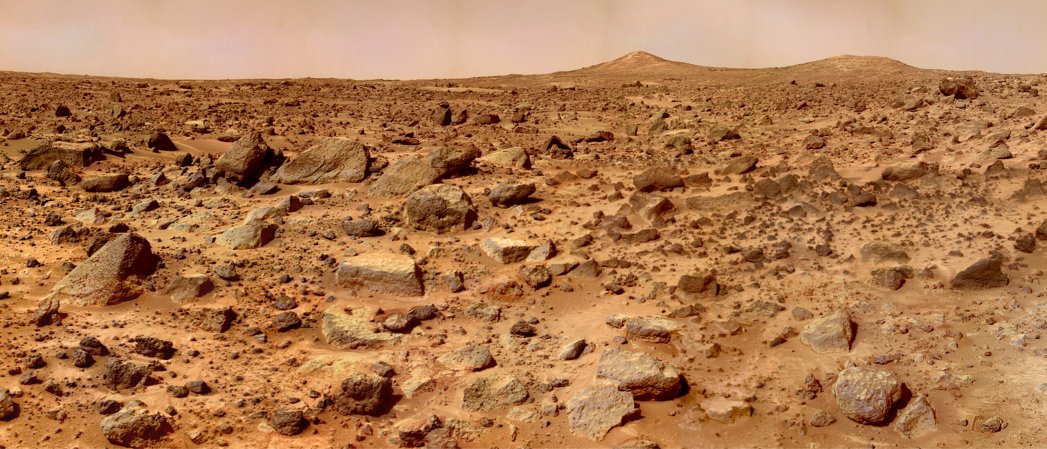

No soil on Earth is a perfect replica of Martian stuff. And like the dirt on our own planet, it's not uniform. Just as the white sand of the Amazon river basin is completely different from the limestone-rich clay in Spain, Mars has a varying geology, and probably a corresponding dirt diversity that humans have not begun to explore. And all the dirt on Earth has had some sort of life stumble into it at some point, even in the relatively barren areas where NASA collects Mars simulation soil. Plants can use the chemical remains of this past life to grow more easily. "There's going to be trace amounts of organic matter," says Palmer. "That footprint is going to be different on Mars."

Scientists have only elemental analyses on a limited amount of Martian soil. Palmer says he hopes to someday have a molecular analysis of dirt from different areas of Mars, perhaps collected by humans. He says that research estimating how much food humans will be able to grow on Mars is crucial to creating preliminary budgets for future manned missions. So while these wormy experiments might not be enough to prove we'll be able to live off the land, they're still important. “We’re getting better,” he says. “You start imperfect and you refine and refine and refine.”