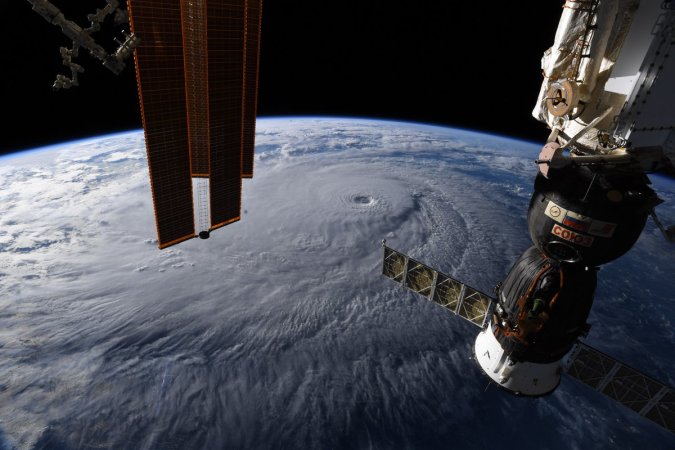

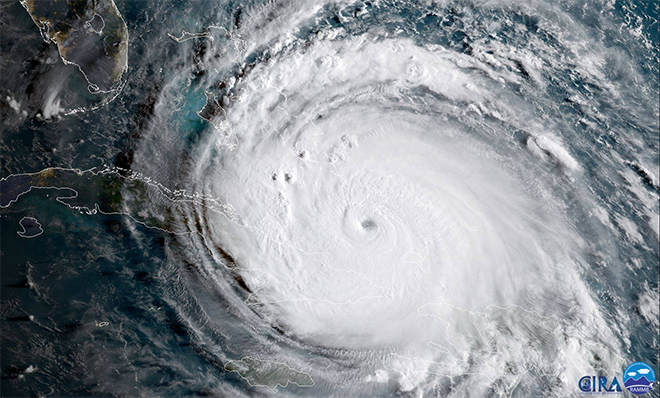

Hurricanes like Dorian and Maria may be disastrous for humans and their property, but some fish have actually evolved to thrive in severe weather.

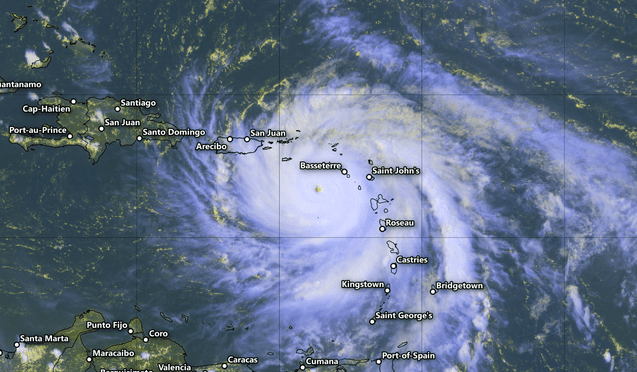

Our team of scientists studied how extreme weather events affect river fish in Puerto Rico. The island is ideal for examining the environmental and human impacts on freshwater fish because Puerto Rico has only nine native species and, unlike smaller Caribbean islands, many inland rivers—46, to be exact.

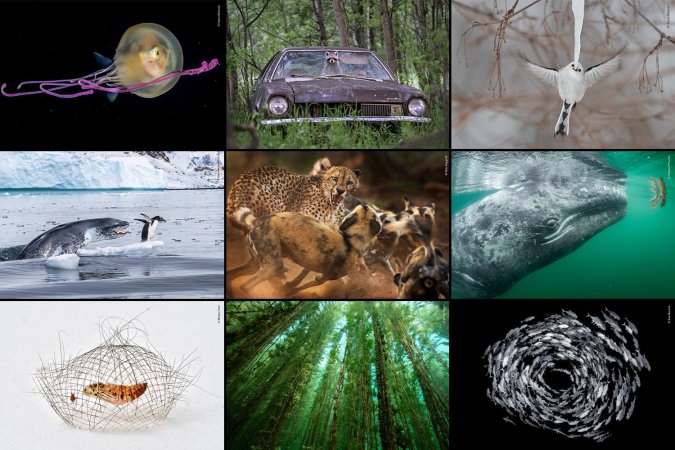

Numerous exotic fish, introduced by humans over the past century, compete for limited food and habitat with Puerto Rican species like the waterfall-climbing sirajo goby, the streamlined mountain mullet, and the bigmouth sleeper, a top river predator.

Because these same native fish are found throughout the Caribbean, their conservation is an important environmental priority for the region. Native fishes are perfectly adapted to their environment and provide services to humans, such as food and nutrient transport. Their presence indicates a healthy ecosystem and clean drinking water.

After Hurricane Maria hit the island in 2017, we discovered that nonnative species—and only the nonnative species—had been decimated by the storm.

Thousands of exotic fish, which are physically adapted to survive drought—not extremely high river flows and flooding—were flushed far downriver during Hurricane Maria, even into the ocean. Many died from blunt force trauma or exposure to salt water.

Native river fish, in contrast, were unaffected by the hurricane. Their body shape and behavior are designed to survive high, fast waters. Puerto Rican fish are actually hit hardest by drought, because they struggle to migrate for reproduction and to find food when waters are low.

Big hurricanes, in short, reset the balance in Puerto Rico’s rivers, favoring native fish over imported species. The same would hold true in rivers across the Caribbean.

So which fish will win the battle for resources in Caribbean waters? The answer may change with the weather.

Climate predictions indicate that the Caribbean will experience both more catastrophic hurricanes and increased drought in the future.

With help from staff and graduate assistants Gus Engman, Bonnie Myers, and Ámbar Torres, we are now conducting experiments to better understand the dynamics between native and exotic fishes in Puerto Rico. We plan to model the future balance between these species—and, hopefully, help keep the Caribbean’s native fish swimming.

Thomas J. Kwak is a professor at the North Carolina State University.

Alonso Ramirez is a professor at the North Carolina State University.

This article was originally featured on The Conversation.